The Fairy’s Hole: Vincent Fecteau’s Caveman Sculpture

11.09.09

“Welcome to my show,” Vincent says.

“Welcome to my show,” Vincent says.

“Your show?” Wilma Flintstone says.

“You did this?” Betty Rubble says.

“We’re going home, Wilma,” Fred Flintstone bellows, barging into the gallery, Barney Rubble behind him. “There’s nothing here but a bunch of fruity-tooty – hey, who’s this guy?”

“This is Vincent Fecstone,” Wilma says. “He’s a famous artist, like Robert Rockenberg or Jasperite Johns.”

“This is art?” Fred roars. “This is crazy-coloured rock!” He stands in front of a Fecstone. A stone sculpture shaped like all different shapes: a slope on a column with a curve coming out from a corner that’s collapsed. It’s bright blue. “Rocks don’t look like this! I’m a quarryman – I’ve lifted a lot of rocks!”

“I’ve lifted a lot of rocks, too,” lisps the plinth, which is a tortoise.

The Flintstones cartoon never featured an artist named Vincent Fecstone; he’s my creation, a caricature of the American sculptor Vincent Fecteau.

The Flintstones never featured an art museum; Bedrock’s Art Museum is based on Chicago’s Art Institute. In 2008, Fecteau showed a clutch of new work at the Institute; I met him for the first time there. Matthew Marks Gallery in New York is showing the sculptures again this autumn, from September 10 to October 24.

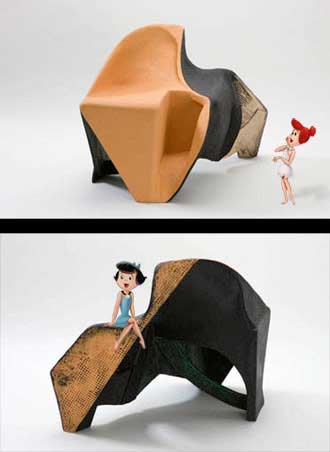

The Flintstones had no influence on Fecteau’s new work, as far as I know; still, his sculptures brought Bedrock to my mind. Fabricated from papier-mâché, they looked like rocks that had been carved into primitive, preternatural shapes, then painted in cartoon colours – the blue of Betty’s dress, the orange of Fred’s tunic.

The Flintstones had no influence on Fecteau’s new work, as far as I know; still, his sculptures brought Bedrock to my mind. Fabricated from papier-mâché, they looked like rocks that had been carved into primitive, preternatural shapes, then painted in cartoon colours – the blue of Betty’s dress, the orange of Fred’s tunic.

“A friend said that they looked like a caveman’s idea of what sculptures are,” Fecteau told me. “I loved that.” I felt they looked like the work of a cartoon caveman, a modern stone-age sculptor straight from The Flintstones – Vincent Fecstone. Cavemen drew deer and water buffalos on cave walls.

Fecstone? He has an abstract bent. He carves stone so that it seems to have been shaped by primeval powers. His sculptures are meta-metamorphic: folded by fake continental collisions, melted by fake magma, cleaved by fake friction. Aesthetics collide like tectonic plates – fake against real, historic against fantastic, decorative against organic. The geological gets illogical.

Fecteau’s sculptures have no natural history; however, they do have an ancestry – fake cavemen, and the fake caves they live in.

Vincent Fecteau looks a lot like Vincent Fecstone. Fecteau is tall and svelte; at forty, he could pass for thirty.

Fecstone is svelte, too. He wears a sabretooth tunic.

Vincent Fecstone studied at Prinstone University. Vincent Fecteau went to Wesleyan. He started showing his art in the early 1990s. He made collages. Then he made small, strange structures from foam core, balsa wood and paper. Critics called them maquettes, models for unbuildable or uninhabitable buildings.

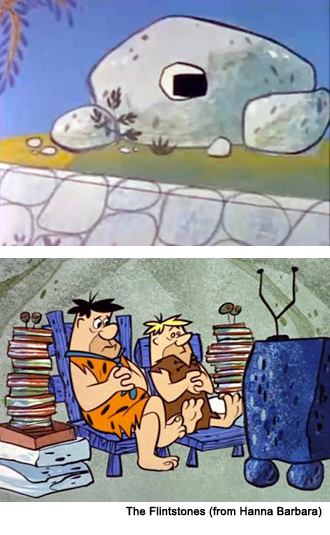

There was nothing Flinstoney about the sculptures, save for the colours. Fecteau favoured a plain palette: grey, brown, black. Buildings in Bedrock are all these same shades. It makes sense – they’re granite, slate, or sandstone. Some are rusty-brown. Perhaps these places were painted with manganese and ochre, like the cave paintings in Lascaux. Maybe they were painted with blood from the Bedrock Butcher Shop, home of the best brontosaurus burgers.

Where does Vincent Fecstone show his work? At Gladstone?

Where does Vincent Fecstone show his work? At Gladstone?

In 2006, Vincent Fecteau contributed a sculpture to a group show at a gallery in New York. Its title: “Untitled.” It was papier-mâché. The pattern painted on it – orange and browny-black – suggested an animal skin, or a faux-stone finish.

This is for sure: the sculpture didn’t resembled a scale building. It looked a bit like an animal bone––a wishbone from a wooly mammoth. It looked a bit like a pretend bone from a pretend beast – a pelvis from a Snorkasaurus.

Fecteau’s “Untitled” would have been at home in the homes of Bedrock’s biggest collectors: the Membership Committee of the Stonyside Country Club; Mrs. Slate, the wife of Fred Flintstone’s boss; Uncle Giggles. It would’ve worked well at Gladstone, or at the Bedrock Art Institute, or at Bedrock’s biannual art fair, Rockumenta. It would’ve been perfect for the cover of Bedrock’s best art rag, Premodern Painters. The Flintstones takes place somewhere between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. In the Hanna-Barberic.

At the Art Institute of Chicago, it was as if Vincent Fecteau stepped into The Flintstones, and Vincent Fecstone stepped out. Fecteau showed Fecstone-esque sculptures, mock-rocks of papier-mâché.

Papier-mâché is the metier of the caveman manqué.

In 1913, D. W. Griffith directed The Primitive Man. It told the tale of a clan of caveman. Ape men attack them, and make off with their women. Cavemen and ape men clash in a battle. A Tyrannosaurus Rex tyrannizes them.

The Primitive Man was one of the first film depictions of cavemen and their world. It was historical hoo-ha. Neanderthals didn’t share space with dinosaurs. The Tyrannosaurus Rex was a canvas puppet, forty feet high. Other dinosaurs were crocodiles with stegosaurus spikes and plates strapped to them.

The film was shot on a set strewn with caves and boulders. In old Hollywood, boulders were brown paper blobs pitted and peaked like rock. Set dressers built boulder-shaped skeletons of rattan, then papier-mâchéd them with newspaper and brown paper. When the boulders were done, the dressers cut them open and extracted the skeletons. Smaller stones were roofing paper stuffed with excelsior.

The film was shot on a set strewn with caves and boulders. In old Hollywood, boulders were brown paper blobs pitted and peaked like rock. Set dressers built boulder-shaped skeletons of rattan, then papier-mâchéd them with newspaper and brown paper. When the boulders were done, the dressers cut them open and extracted the skeletons. Smaller stones were roofing paper stuffed with excelsior.

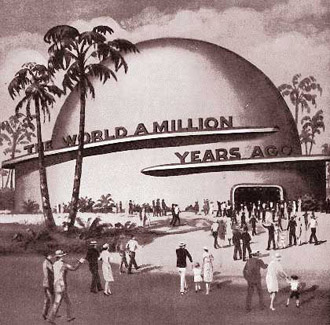

Messmore & Damon Inc. were the masters of prehistoric-seeming papier-mâché. George Harold Messmore and Joseph Damon started out crafting papier-mâché floats for parades, then moved into window display and amusement park rides. In 1925, they made a model Brontosaurus to promote a film adaptation of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World. The beast stood in the lobby of a New York City cinema. It was twelve feet long. It moved: motors were hidden in its head, neck, torso and tail.

“The World A Million Years Ago” was Messmore & Damon’s contribution to the Chicago’s World Fair in 1933. Fairgoers rode through a red dome on a moving walkway. They rode past a display of cavemen. They rode past a pit full of papier-mâché dinosaurs and boulders. All the periods of dinosaurs were represented. From the Jurassic, the pterodactyl; from the Pliocene, the Giant Sloth; from the Pleistocene, the Mammoth. The Mammoth had thirty-two primary movements and 800 secondary movements. The Brontosaurus could bend its neck and bite the hats of fairgoers.

Dinosaurs, Neanderthals, rocks – they were papier-mâché. What does it mean when flesh and fossils are the same stuff?

Is time composed of paper, gesso and glue?

“It’s art,” Vincent says.

“It’s not art,” Fred says.

“Fred, you can be such a Neanderthal!” Wilma says. “Vincent’s showing us what’s inside his soul.”

“Vincent is?” says a bird. It’s in Vincent’s hand. It’s what he uses instead of a chisel. “He gets the glory. I get the broken beak.”

“Art’s supposed to look like something,” Fred says.

“I don’t know, Fred,” says Barney. “These sculptures look like something.” He’s scoping out Fecstone’s sculptures, which are all titled “Untitled.” He points to “Untitled.” It’s purple. “This here looks like an off ramp. Or a water slide. Maybe it’s a model of a ride? I could see it at Rocky Island. You walk in here, then climb here, then slide down here.” He points to a hole. “I don’t know what this does.”

“Who paints a rock purple?” Fred says.

“Who paints a rock purple?” Fred says.

“Andre does,” Wilma and Betty say at the same time.

“I know Andre,” Vincent Fecstone says. “He does my hair.”

The Flintstones never featured an artist named Vincent Fecstone. It did have a hairdresser named Andre.

In the show’s second season, Wilma and Betty have their hair done at Andre’s Beauty Parlor. Andre has a French accent. A French moustache. His hair is white. His bowtie is white, and big – a bow tie Oscar Wilde would have worn, or Snagglepuss.

After shampooing the ladies’ locks, Andre accompanies them to the hair driers. The driers are hollowed-out rocks, hard hoods hanging from dinosaurs’ necks. The dinosaurs are purple. The salon is painted lilac. Andre’s in a lavender pelt.

Bedrock is chock-a-block with caricatures. Fred is a belligerent, blue-collar bowling fan. Fred’s boss, Mr. Slate, is a white-collar curmudgeon. Fred’s mother-in-law is a bossy, blue-rinsed nag. Andre? He’s a fairy. The tell is his palette. Fairies love flamboyant colours.

Vincent Fecstone is a fairy, too.

In The Flintstones, Bedrock is depicted in grayish earth tones. Fred and Barney wear stone-tones – browns, grays and rusts. Their haircuts are lousy; both cavemen boast cowlicks.

Andre favours mauve. He’s a master colorist – you don’t think Wilma’s a real redhead, do you? Like Andre, Vincent Fecstone plays with the power of cosmetic colour: he carves rock and then paints it colours rock couldn’t be. Vincent Fecteau is even faker than Vincent Fecstone: He made papier-mâché into real-looking fake rock, then made the real-looking fake rock look fake by painting it in gay, garish hues.

Andre favours mauve. He’s a master colorist – you don’t think Wilma’s a real redhead, do you? Like Andre, Vincent Fecstone plays with the power of cosmetic colour: he carves rock and then paints it colours rock couldn’t be. Vincent Fecteau is even faker than Vincent Fecstone: He made papier-mâché into real-looking fake rock, then made the real-looking fake rock look fake by painting it in gay, garish hues.

“A lady said that she liked my sculptures,” Fecteau told me at the Art Institute of Chicago, “but that the colours ruined them. I thanked her. That’s what I wanted them to do.” If something in Fecteau’s forms seems familiar, it’s defamiliarized with colour. If something seems realistic, colour falsifies it.

Andre is a fake cave fairy. Vincent Fecteau is a fake fake fairy.

Fake fairies and fake caves have a colourful history.

Is the Great Gazoo a fairy?

The Great Gazoo was a character on the last season of The Flintstones. He was an alien who’s been banished to earth.

I don’t believe he’s a fairy in the homosexual sense. Though he does drawl in a most affected manner, and he quips: meeting Fred and Barney for the first time, he says, “Did it ever occur to you two that nature was less than kind?”

In folklore, fairies are fabled creatures that frolic in the British Isles. The Great Gazoo had a fair bit of fairy in him. He was green. According to Answers.com, fairies’ preferred colour is green, “not only for dress but sometimes for skin and hair as well.” Gazoo popped up without warning, like fairies, who “are often invisible or can become so at will, often by donning a magical cap.” Fairies “prefer to live underground, especially under a hill, in a cave or burrow.”

Fake fairies? They live in grottoes.

Fake fairies? They live in grottoes.

A “fairy hall.” This is how Dr Johnson described a grotto that the poet John Scott built in the 1750s and 1760s. Grotto is another name for an artificial cave.

In Georgian England, fairy grottoes were fashionable follies. The upper class constructed them under their gardens or homes. They contemplated in them. They threw dinner parties in them. Mostly they showed them off.

Scott decorated his grotto with thousands of sea shells. It was the style of the day. Ships loaded with sea shells docked in port towns every day. Shells from India, shells from Africa – though they cost a fortune, there were never enough of them to outfit the fairy grottoes being built across the land.

Between 1720 and 1725, Alexander Pope built a shell grotto at his house on the Thames by Twickenham.

In the 1730s, he scrapped the shells. He redecorated, studding the walls with specimens of minerals and stones. In Surrey, a barrister by the name of Charles Hamilton glittered his own grotto with walls with gypsum flakes and purple fluorite crystals.

Forget shells. It became fashionable for fairy grottoes to replicate limestone caverns. Passages into grottoes were decorated with grotesque-cut stones: flints, rough stones, stones cut to appear irregular. Tunnels were constructed of holey limestone rocks which were pinned in place. Furnace slag slathered on walls resembled volcanic lava. Furnace slag contained copper; walls had a blue hue. Green wax was melted and applied to it to simulate moss.

Fairy grottoes were gaudier and glitzier than any limestone cavern ever was. Mica, shards of green glass, and fragments of mirrors made them glint. Suspended from ceilings: chandeliers of fake stalactites. They were made of timber cones slathered with lime mortar and studded with gypsum flakes and geodes. “Bristol diamonds” were chunks of calcite. Floors consisted of shards of coloured marble. At Goodwood, a grotto floor was made of polished horses’ teeth. At Pontypool, a grotto floor was made from the knuckle-bones of sheep.

Fairy grottoes were gaudier and glitzier than any limestone cavern ever was. Mica, shards of green glass, and fragments of mirrors made them glint. Suspended from ceilings: chandeliers of fake stalactites. They were made of timber cones slathered with lime mortar and studded with gypsum flakes and geodes. “Bristol diamonds” were chunks of calcite. Floors consisted of shards of coloured marble. At Goodwood, a grotto floor was made of polished horses’ teeth. At Pontypool, a grotto floor was made from the knuckle-bones of sheep.

Americans didn’t decorate fake caves with cave fakery; they made their natural caves look unnatural:

In 1895, Charles Darrow homesteaded in Colorado. On his land: a limestone caves full of spectacular speleothems. Stalagmites, stalactites, columns – speleothems are rock features that form in caves.

The Fairy Caves – this is what Darrow called his caves. He was hardly being original. There was a Fairy Cave in Missouri, and a Fairy Cave in Texas. Cumberland Caverns were also called Fairy Caverns. Carlsbad Caverns had a Fairyland cavern. Quebec had The Fairy’s Hole.

The Fairy Cave Co. – this is what he called his company. He decided to open his caves to the public. Admission: fifty cents. He wanted to make his cave a show cave, a tourist attraction akin to Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave, which contained a cavern called The Fairy Grotto.

He wasn’t content to merely call his caves fairy caves. He turned his caves into fairylands. How? He became the first cave operator on the continent to light a natural cave with electricity. Caves are dark. Caves are almost always colourless: most speleothems are mud-coloured. The lights weren’t there to spotlight speleothems; they were there to add atmosphere, and artifice.

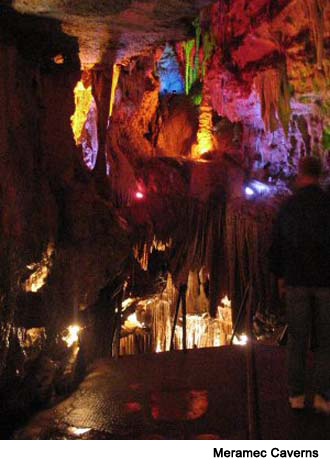

“These caves,” Darrow wrote of his Fairy Caves, “are all lighted with electricity, producing a spectacular effect of sparkling brilliancy, relieved only by fantastic shadows …” Show caves across the continent soon became electrified. Cave operators bathed speleothems in bright blue, green, purple. Some staged shows: at Meramec Caverns in Missouri, multi-coloured lights shone against a curtain of flowstone. At Cumberland Caverns, a crystal chandelier hung from the ceiling of a cavern.

The Fairyland Caverns in Georgia were the gaudiest of all. The caverns were ancient; their owners dressed them up. The tunnel into the caverns was decorated with rose quartz, smoky quartz, and dogtooth quartz. Coral decorated the ceiling. The coral had been dyed pink. Fairy figures cast from clay were posed in fairy-tale dioramas. The caverns were lit with black light: fairies glowed in ungodly oranges and greens. Cave lights were concealed behind fake cave formations of fake rock.

The Fairyland Caverns in Georgia were the gaudiest of all. The caverns were ancient; their owners dressed them up. The tunnel into the caverns was decorated with rose quartz, smoky quartz, and dogtooth quartz. Coral decorated the ceiling. The coral had been dyed pink. Fairy figures cast from clay were posed in fairy-tale dioramas. The caverns were lit with black light: fairies glowed in ungodly oranges and greens. Cave lights were concealed behind fake cave formations of fake rock.

Wouldn’t Vincent Fecteau’s sculptures make wonderful sconces at Fairyland?

“David?” Vincent Fecstone says.

“Yes, David!” Fred Flintstone says. “By Michelangelstone. There’s a real sculpture for you. You don’t see him all covered in clown paint.”

The Great Gazoo manifests himself.

“Gazoo!” Fred says. “Don’t tell me you like this stuff?”

“Dum-dum,” Gazoo says. “These sculptures are a scream. It’s geology in drag, the earth in camp costume. What if the planet was pansy? What if stone itself was sissy?”

“That would explain Cary Granite,” Barney says. “And Rock Hudson.”

“What if nature created unnatural shapes?” Gazoo says. “What if nature came in unnatural colours? I see what Mr. Fecstone is doing. He’s making Mother Nature out to be middlebrow. What if he could sculpt something as singular and strange as something that nature made? What if nature could create something as singular and strange as one of his sculptures? What would that mean?”

I have been to Bedrock. Bedrock City’s an amusement park in Arizona. It’s built from cement. A volcano towers over it. A tram takes visitors into and out of the volcano. Visitors slide down the tail of a bronotosaurus, as Fred Flintstone does at the start of each episode of the cartoon series.

I have been to Bedrock. Bedrock City’s an amusement park in Arizona. It’s built from cement. A volcano towers over it. A tram takes visitors into and out of the volcano. Visitors slide down the tail of a bronotosaurus, as Fred Flintstone does at the start of each episode of the cartoon series.

Colours are crazy: it’s like the builders slaughtered a slew of dazzlingly-coloured dinosaurs and painted the town with the beasts’ blood. Or they bled the Banana Splits. Palm trees are turquoise. The gas station is garish yellow. The schoolhouse is white on the outside, powder blue inside. The schoolteacher’s dress is concrete painted purple. The class’s globe is a hunk of rock – it’s not round, nor smooth; it’s a boulder.

Andre’s Beauty Salon is green. A showcase contains wigs. A yellow hairclip is huge enough to hold back the hair of a mammoth. A blue hair drier hangs from the ceiling inside, a stalactite of sorts. Caves and beauty parlours go back. There is a cavern called The Beauty Parlor in the Diamond Caves in Kentucky. In Wind Cave in South Dakota, The Beauty Parlor is a cavern coated with micaceous clay. The clay’s red. A century ago, it was scraped out and sold as rouge.

The Flintstones cartoon went off the air in 1966, three years before Vincent Fecteau was born. Bedrock City was built in 1972. It’s seen better days. Sun and sand have battered the buildings. Statues of the Flintstones and Rubbles seem as brittle and breakable as Cocoa Pebbles, or vitamins.

Flintstone vitamins. Pebbles are purple.

––––

first page graphic is Untitled by Vincent Fecteau and Wilma and Betty by Hanna Barbara, mashed by Robin Brasington