The Existence of Fire: An Interview with Sara Woods

03.02.15

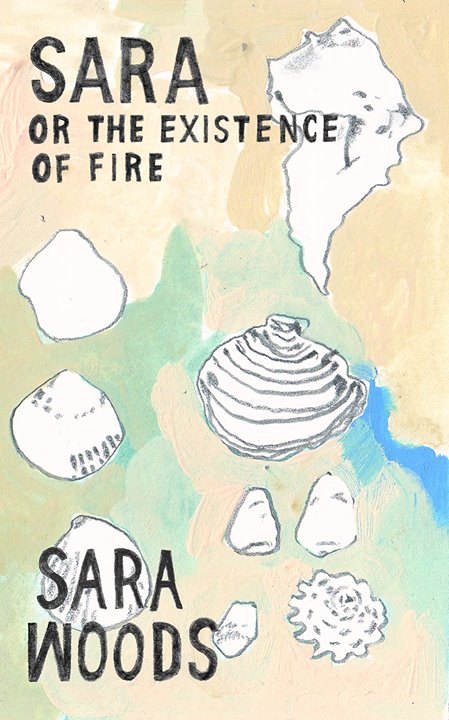

[Paul Cunningham and Sara Woods got together over email to discuss the magical “ongoingness” of her book, Sara, Or the Existence of Fire (Horse Less Press, 2014)]

Paul Cunningham: “She said I am here for moving and fire.” This was one of my favorite lines in the book and when I read it I was instantly reminded of the mysterious red vase mentioned near the beginning: “The vase didn’t know why it was there. None of us do.” I thought about Sara (the arsonist version of the character) and I thought about the trees that all those houses came from. And the roots that all those trees came from. I thought about a death drive. Is there a connection here between what goes into a vase and what goes into a fire?

Sara Woods: I think there is definitely a connection. I think the thing about these poems is that when I was writing them I was trying to write about all of the hard feelings I had about the world—and especially about my life at the time I was writing this—that I didn’t have an answer for. Just dump all of these things together and make some kind of parable out of it. The vase doesn’t know why it’s there and I don’t think Sara does either. I think in that moment she is cynically resigning herself to the idea that she exists only to do the things she is already doing. Set up a life, realize she is still trapped, still miserable, and then burn it down and start over until she says fuck it and moves to a place that’s already burning. My partner Irene and I started reading Descent of Alette together, taking turns reading it aloud, and there was this word “ongoingness” that just came alive off the page when I said it. I put down the book and wrote that word really big on a sheet of paper. Irene was just like “Totally. That.”

PC: I won’t be forgetting the poem in which Sara cleans her dog’s paws with her teeth anytime soon. Sara definitely has an affinity for animals. So much that they sometimes haunt her daily thoughts. Could you talk about the animals in this book? Whether she’s worrying about the animal products she’s consuming or imagining her living space is temporarily inhabited by imaginary dead trees, I sometimes thought of Sara as a remorseful reverse-Goldilocks. Accurate?

SW: I hadn’t thought of the Goldilocks comparison, but that’s really good. Sometimes I think of all the animals in this book as these shitty spirit guides that don’t have any wisdom to share or really any special knowledge about anything. They’re these outside observers that are kind of vaguely worried about her and hope she’s okay but can’t really do anything about it. They can’t change anything. Also I would point out that she’s not worrying about the animal products she’s eating, it’s the animal products she’s eating that are worrying about her. Or maybe kind of gossiping about her at least. She’s distinctly in a not-good place throughout most of the book, except for these little moments of beauty or silence she gets to inhabit occasionally.

PC: Flies come before decomposition in this book. I was also disturbed by the way worms surround Sara—and all of her fingers—as if she were already dead. Though, she does fall asleep to shuffling mourners’ feet every night. Is this a moment of death in life? Or, like an earthworm, is Sara strong enough to live off of the dirt? In other words, despite the world’s disorder and disarray, is Sara putting all of this excrement to good use? It sometimes feels like Sara is trying to imagine herself into non-existence.

SW: I don’t know if Sara is strong. I’d like to think she is strong. She definitely keeps living. Even when she dies she keeps living. Death-in-life is a big thing in the book, in all the places you mentioned and in a lot of other places as well. The ongoingness as a kind of death. The only answer I think anyone gets is what her dog gets at the end, which is basically just curing ongoingness with more ongoingness. It’s pretty bleak when I go back and try to piece together what I was writing about in a big-picture way.

PC: This is a very funny book, but also a very heartbreaking book. I think the magical quality of the writing has something to do with that. Can we talk about magic? You’ve described your writing as magic before and I think it becomes most complex in lines like, “Her mother was made of moths, and Sara used to go to sleep with a light by her bed so her mother would gather near her while she slept, their warm dog lying across her legs.” And that’s just one excerpt from the first poem. But I think one of the things that makes your writing stand out so much is that it’s never lazy. You could have stopped after “Her mother was made of moths,” but you pushed the plurality of the image to a point where one can sense both distance and comfort. Is this book a way for you to carve a path through all the chaos with a bit of magic? A familiar cloud here, an oddly familiar smell there?

SW: I actually really, really believe in magic. I can just feel it sometimes. I don’t think I’ll ever get tired of writing about magic. But I have another poem, not in this book, where I wrote the line “People like drugs because they’re the closest to magic, but real magic exists, it just doesn’t care what we want & I don’t blame it.” That is very much how I feel about magic. I can feel it all the time, I know it exists, but I think you won’t get anywhere trying to control it. I also think the impulse to always want to control is kind of fucked. In Sara’s world, magic is everywhere, and it doesn’t fix anything. It’s not a solution, it’s just there, just part of the water. Nobody has any magic powers because, again, fuck power & control. What magic does, sometimes, is give her these moments of beauty she can live in. Sometimes it also kills her and her dog with flies.

PC: And, speaking of magic: Sara’s mouth produces seeds. She waters them with “nonsense” whispers. Later, the dog’s mouth spits up 12 dead wasps. But the dog doesn’t remember eating any wasps. Why? Maybe he’s been too worried about paying his rent. Every month the dog vomits into a trumpet to pay rent. Why are these bodies pushing out all of this life and death? Or is this just what bodies do? Additionally, there’s a lot of nonsense in this book and I couldn’t be happier. (Whispers) Do you think some poets have forgotten that this whole poem thing can sometimes be fun?

SW: Being disgusted by your body (admittedly, in some pretty specific ways) is pretty much criteria number one for being trans, and I think I was channeling this in some more general ways throughout the book. In the seeds poem, Sara gives birth to the wrong thing in the wrong way but makes the best out of it. Her dog has a harder time of it. This is absolutely what bodies do.

I kind of wish I knew what the nonsense whispers Sara said were. I feel like they would be some next-level nonsense and that sounds great to me. I think nonsense is fun. I think the idea of an “efficient” poem that doesn’t “waste” words is weird and feels like we’re importing all these horrible capitalist ideas about how things should be done into the creative world. Bring on a little silliness. There was an early reader of this manuscript, a fairly prominent and well-decorated poet who gave me this horrible condescending feedback when I sent it in for consideration by a small press. Ultimately he just didn’t understand or care about the book, and that’s fine, because I felt the same way about his book. His just won more awards. But the one poem he hated the most was the one where Sara’s dog falls asleep in a salad and uses a tomato for a pillow. After that I knew no matter what that I wanted to keep that one in there.

PC: I’m glad you kept that poem in there because, honestly, the first thing I thought of was what Gertrude Stein writes about salad in Tender Buttons: “It is a winning cake.”

Urine imagery, or the act of urinating, was another thing I found very intriguing about this book. Early on, Sara describes how, as a child she used to pee in her bath to forcibly change the color of the water. Later, after the houses have been burned down, I was floored by this passage regarding a river: “She laid down in it face first and kicked the water as hard as she could. She kicked the water pretty hard. She thought about the torch and the apartment and before and then she stopped thinking about it. Sara wanted to feel wanted. She thought maybe she was wanted now, for arson.” Since, again, Sara is postured like the young Sara from the early bath poem, I began thinking about a possible relationship between fire and urine. How both of these things are used to exercise control over a field of vision. I also began thinking of fire and urine as artistic tools (i.e. Cai Guo-Qiang, Andre Serrano). Any thoughts on this?

SW: Peeing is always something that has been really comforting to me. Some embarrassing stories about peeing my pants as a kid aside, I think I’ve used a retreat to the bathroom to escape all kinds of anxiety throughout my life, and somehow at some point peeing and pee began to feel really comforting and safe to me. I think “Piss Christ” is a really gorgeous photo. I think for me the connection between urine and fire is maybe like, this giving up control. When she pees in the bath, what she’s really doing is just not holding it anymore. Maybe lighting everything on fire is just another way of not holding it anymore.

PC: The poem in which the idea of a date becomes a sort of mass ornament was one of my favorites. Lines like “Men and women of all ages,” seem to emphasize how the concept of dating has become some sort of public spectacle. How everything is just expected to somehow exist as public knowledge. Kind of gross.

SW: That poem specifically was written about experiences I had with online dating at the time. I didn’t have any horrible dates. I would always go on a date and feel like the person was perfectly nice, but in a way, they kind of could be anyone. It filtered in a way so you had these superficial common interests and etc., but the date always felt like I was out with the roommate of someone I could have been in a relationship with and after awhile they all blended together into this mass of people that weren’t quite right. But it wasn’t terrible. They were good people. I like your interpretation too, though.

PC: Despite this being a moment in the book in which Sara was told her life was wrong, the coded rain poem was one I can’t get out of my head. Maybe even liked? I think it was each pause I read before the raindrops hit. How we sometimes know something bad (i.e. weather) is on its way and how it needs to just hurry up already. How we sometimes attempt to transcribe the agony of waiting. I think there’s a rhythm in agony. It’s a kind of rhythm of living, maybe? And it gradually becomes something detrimental, grating. It reminds me of something Sara says later: “It doesn’t matter much where you’re falling to.” After a while, I think readers will just accept the dream logic of Sara’s world. Whether she’s 100 years old or 10,000 years old, what matters seems to be whatever one is experiencing—whatever Sara is experiencing—during this existence of fire.

SW: Yesss. Totally. That’s the ongoingness.

–––––