Son of Kong

15.01.06

Of the scenes dominating my earliest memories, the most indelible played originally in two Denver theaters.

Of the scenes dominating my earliest memories, the most indelible played originally in two Denver theaters.

The first of these theaters wasn’t actually a performance space, but a kitchen in a house on Humboldt Street, where, when my father arrived home from work, a necktie barely loosened yet from his tree trunk neck, a marriage unraveled in yells. Unhappy families, we can infer from Tolstoy, will each dissolve in their own fucked-up style. This was my parents’.

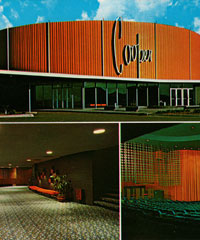

The second place was a refuge from the first, the Cooper Theatre two miles away on S. Colorado Blvd. A low, stumpy silo painted a majestic shade of rust, the building sat along the road knowingly, like a fat Buddha to whom I paid matinee-rate homage on those afternoons when my mother needed to get away from that house. The panoramic Super Cinerama screen inside had a pronounced curvature, engineered to join images from three synchronized projectors. When the Cooper opened its doors in 1961 this screen was the biggest in the country—38 feet high, 105 feet wide. The Cooper wasn’t just immense, it was plush. A Saturday night destination for a booming cattle town’s kings. A place to bring their families (or possibly, to take their mistresses, a luxury both my father and his father indulged). For the occupants of 814 seats, the parking lot could accommodate as many as 400 cars. Between shows, drapes matching the hue and corrugated surface of the exterior hung across the screen, and on either side of the floor were these swank, open-air smoking lounges from which a dame and her Lucky Strike could still see the feature. Later when I took up cigarettes, I imagined myself reclined along these shallow sofas, a bitchy wit in a Wilde play installed at his divan. Because of the Cooper, I’ve made a lifelong wastrel’s practice of avoiding responsibilities or bad decisions or poorly selected girlfriends—of being for 120 minutes elsewhere—by hiding in the dark.

It does not seem possible that this inviolable orange tin can—razed in 1994, usurped by a Barnes and Noble—is gone. It had seemed as constant as a battlement wall erected to keep out a beast. And it was at the Cooper in December 1976, no more than a week before my mother filed for divorce and my father moved out, that she took me to see a movie in which just such a wall comes down.

I understand myself now as the mud stamped by one of those huge footprints, mainstays of all three King Kong movies—the 1933 original, John Guillermin’s 1976 update, and the new 3.0 Peter Jackson rendition. But at the time, I had no awareness that a 40-foot gorilla had beaten his paws into my four-year old consciousness. My movie was Star Wars, which I first watched at the Cooper the following May. On the sidelines of the cartoonishly acrimonious divorce my parents waged were unusually pliant adults—grandparents, a favorite aunt and her boyfriend. All of these kind people were eager to lend diversion, even if that meant another schlep to the Death Star. None of them realized this, but during the year it took my folks to split up, I got to see Star Wars twenty-one times.

I understand myself now as the mud stamped by one of those huge footprints, mainstays of all three King Kong movies—the 1933 original, John Guillermin’s 1976 update, and the new 3.0 Peter Jackson rendition. But at the time, I had no awareness that a 40-foot gorilla had beaten his paws into my four-year old consciousness. My movie was Star Wars, which I first watched at the Cooper the following May. On the sidelines of the cartoonishly acrimonious divorce my parents waged were unusually pliant adults—grandparents, a favorite aunt and her boyfriend. All of these kind people were eager to lend diversion, even if that meant another schlep to the Death Star. None of them realized this, but during the year it took my folks to split up, I got to see Star Wars twenty-one times.

Further postponing my reckoning with the ape, a delay I’m aware that I’m re-enacting as I write, was Merian C. Cooper’s and Ernest B. Schoedsack’s RKO classic, which disappointed me when I caught it on TV not long after. Cooper (no relation to the Denver theater) was a techno pioneer who helped develop the Cinerama format and in 1952 directed This is Cinerama, a trippy showcase for widescreen’s proto-IMAX intensity. Cooper and Schoedsack hardly invented stop-motion animation—a technique still current in the 1970s, when the great Ray Harryhausen, a Kong devotee since he was ten, made his Sinbad pictures—but they did whip up stop-motion’s first masterpiece.

As a kid who got his ass kicked regularly for no good reason—having Strong for your last name will do this to you—I knew fights were sloppy, unpredictable affairs, and I felt compassion for stop-motion’s integrity. Pinned under countless bullies, I have wriggled as awkwardly as the dinosaurs Kong throttles.

No, it wasn’t the clay lumps that turned me off, it was the humans. I have never appreciated the draw of Fay Wray (who’s as glamorous as a kewpie doll). Her Ann Darrow doesn’t even like Kong, she’s disgusted by him. She spends the movie in a faint. Then there’s her sailor love interest, Jack Driscoll (spindly Bruce Cabot). When Kong ascends the Empire State building, it’s Driscoll’s idea to send in airplanes to “pick him off.”

Children intuitively identify with Kong of course. His eyes contain multitudes in no way discernible in Wray’s or Cabot’s. The film critic Michael Atkinson remembers “the roaring angst of lost simian rage, ass-whupping the grown-ups and yowling for our own damaged innocence.” Or as Dino De Laurentiis, the flashy Italian producer behind the 1976 remake, put it, suggesting that he understood better than Cooper and Schoedsack where our sympathies lie: “When the monkey die, everybody cry.”

Children intuitively identify with Kong of course. His eyes contain multitudes in no way discernible in Wray’s or Cabot’s. The film critic Michael Atkinson remembers “the roaring angst of lost simian rage, ass-whupping the grown-ups and yowling for our own damaged innocence.” Or as Dino De Laurentiis, the flashy Italian producer behind the 1976 remake, put it, suggesting that he understood better than Cooper and Schoedsack where our sympathies lie: “When the monkey die, everybody cry.”

This was too much for me, I was only four. I had my fill of animal roars at home. I preferred sanctuary further away, and I didn’t think about giant apes again until 1981, when John Guillermin’s Kong—The Legend Reborn was its working title—began playing in heavy rotation on TV. Typically, the movie straddled two nights, expanded with nearly 45 minutes of footage edited from the 134-minute theatrical release. (Unforgivably, these scenes are missing from Paramount’s bare bones DVD.) The initial sight of that wall, still intact, or of Jessica Lange in her titillating little black I. Magnin cocktail dress, or (and this, damn it, isn’t on the DVD) of a safari hat pancaked on the turf in Shea Stadium by Kong’s foot; unexpectedly, a horde of rough images delivered me back to a seat at the Cooper.

By then, those afternoons were three states behind. My mother had removed us, me and my sister, to California. In Denver, my dad’s job working for my grandfather’s electrical supply company had paid for a stately house with a cavernous basement that I thought of as my lair when the backyard was too cold to play in. But there was no basement in California, nowhere was underground. It never got too cold to ride a bicycle outdoors, and our condo’s backyard was a 20’ x 10‘ bucket, wrapped on three sides by a high cinderblock wall. My mother bricked over the dirt out there as soon as we moved in. She didn’t want to pull weeds, she said.

The divorce was past us (I saw my dad periodically for a few years, then not at all shortly after he remarried) but what my mom still liked to do on weekends was run to the movies. The theaters we drove to most—for example, the United Artists Twin or the Alondra 6—were modest suburban venues whose once fresh carpets preserved black moles of chewing gum. Some of these places had “loge” seats in the rear with thicker cushioning that cost more, but except for the Lakewood Pacific, my favorite, none had ever aimed for grandeur. At the Pacific, a glass chandelier still dangled from the vaulted ceiling above the concession stand, and the larger of its two screens was maybe half the size of the Cooper’s and must have been built around the same time. In any case, the Pacific’s glory days were over. The interior fairly sulked in pallor and neglect, burdened as it was from the start by its mustard yellow color scheme.

Stranded in a flatland of puny theaters, I privately claimed the Kong myth as a parable for my exile. One innovation Jackson’s film gets exactly right is to set the Manhattan finale in winter, when the concrete jungle is least like the one Kong comes from. A few weeks before writing this, watching the moment when Kong slips on a frozen pond in Central Park, then skates across it on his surprised, graceful monkey butt—when the monkey dance, everybody cry—suddenly I was hurling snowballs one December night fifteen years ago, months after I’d escaped California and gone east for college somewhere exotically cold.

Stranded in a flatland of puny theaters, I privately claimed the Kong myth as a parable for my exile. One innovation Jackson’s film gets exactly right is to set the Manhattan finale in winter, when the concrete jungle is least like the one Kong comes from. A few weeks before writing this, watching the moment when Kong slips on a frozen pond in Central Park, then skates across it on his surprised, graceful monkey butt—when the monkey dance, everybody cry—suddenly I was hurling snowballs one December night fifteen years ago, months after I’d escaped California and gone east for college somewhere exotically cold.

That feckless freshman would never have made these sorts of connections between Kong and his prelapsarian memories. He was straining to fit in with the boarding school tastes of his college peers, and he tended to act the part of a type, a public school kid who was grateful to be there, which he was. The genre movies he grew up on were packed up, discarded toys hibernating in his mind’s attic.

I hadn’t read Walter Benjamin yet or Proust, but probably they couldn’t have saved me from my treachery. Nostalgia, I had decided, was a child’s security blanket, and to prove my discipline and intellectual maturity I wanted to stand naked. I also hadn’t read any Susan Sontag, and knowing too little about camp I was embarrassed of the jokes in Lorenzo Semple Jr.’s script for Kong ’76 (“Let’s not get eaten alive on this island. Bring the mosquito spray.”)

To cover up, I declared my alienation through legitimate pictures from the same period—McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Conversation, The Shining. Yeah, these were genre pictures too, and I really cared about them, but the important thing was that auteurs had made them. These guys had cleared the hurdle of the syllabus. John Guillermin, on the other hand, made such films as Tarzan’s Great Adventure, Tarzan Goes to India, Shaft in Africa, Death on the Nile, and Sheena. He was a workman director, who had long ago parked whatever vision he possessed at the cross streets of B frivolity and Orientalism. De Laurentiis picked Guillermin to direct the remake because he’d scored a hit in 1974 with, um, The Towering Inferno. Count the albatrosses. Then add to them the ineradicable fact that Guillermin also helmed King Kong Lives (1986), a sequel in which our hero turns out to have survived his fall, but needs a blood transfusion and an artificial heart transplant if he’s going to pull through.

Understand, almost no one will tell you that Kong ’76 is a good film. Pauline Kael of all people enjoyed it and it made a bundle ($24 million) upon release, but the legend goes anyway that Reborn bellyflopped. Among the notices for Jackson’s movie that mentioned this predecessor at all, “best-forgotten” was the common denominator. David Denby ran right over it in the New Yorker (“rather cheesy”). And in the New York Times A.O. Scott dismissed it, also in one sentence, for trying to “drag the story into the corporate present.”

Understand, almost no one will tell you that Kong ’76 is a good film. Pauline Kael of all people enjoyed it and it made a bundle ($24 million) upon release, but the legend goes anyway that Reborn bellyflopped. Among the notices for Jackson’s movie that mentioned this predecessor at all, “best-forgotten” was the common denominator. David Denby ran right over it in the New Yorker (“rather cheesy”). And in the New York Times A.O. Scott dismissed it, also in one sentence, for trying to “drag the story into the corporate present.”

Exactly how the Hoover economy of 1933 belongs any less to our corporate present than the national energy crisis of the 1970s (the backdrop for Guillermin’s Kong) isn’t at all obvious to me. What I do know, having lived intimately for thirty years with this cinematic orphan, is that its droll cynicism has a lot more relevance in 2006 than Jackson’s software demo. Guillermin opens in an Indonesian port, where a cruiser belonging to Houston-based fuel company Petrox disembarks for unchartered Skull Island. Instead of Carl Denham, a maverick film director looking for a wild location (Robert Armstrong, whose character survives for Son of Kong), the man in charge here is Fred Wilson (Charles Grodin), a Petrox executive hungry for untapped crude. He believes he’s spotted evidence of some in NASA satellite photos taken over the South Pacific. “I personally got hold of the super classified pictures via a donation I made to someone in Washington D.C.,” Wilson says. “No names, but I think he lives on Pennsylvania Avenue.”

Let’s shelve these satisfying jabs at White House corruption and my personal history with the ape for a moment. There are some broader themes in Kong we need to discuss: a white panic, more or less, over black male sexuality; an indigenous culture stripped for parts. Slavery. Parse it how you want, the Kong myth is always already about Western imperialism.

Peter Jackson gets this, sort of. One of his sailors (who’s black) recites cautionary passages from Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, that unsparing critique of European rationalism’s limits—or, depending on whom you ask, a rally for the white man’s burden. Jackson’s South Pacific natives wear blackface. And for the stage scene in New York, the director recreates in detail the Polynesian chintz of the 1933 village. Yet when the natives maraud—something they never do in the earlier films—Jackson’s winking eye shuts, and the camera jitters nervously like he’s just seen Tolkein’s orcs. We’re left to judge savagery at face value.

I can’t defend Guillermin’s equally bizarre choice to use black actors and—African!?—costumes for Skull Island’s people, but his is the only one of the three films to confront its global politics head-on, and the only one honest enough to document the middle passage. Kong has never, in any version, looked so defeated as when he lies slumped in a corner of a Petrox supertanker’s hull. He knows that he’s crossing the ocean between subject and object. He’s a commodity now, something for sale.

I can’t defend Guillermin’s equally bizarre choice to use black actors and—African!?—costumes for Skull Island’s people, but his is the only one of the three films to confront its global politics head-on, and the only one honest enough to document the middle passage. Kong has never, in any version, looked so defeated as when he lies slumped in a corner of a Petrox supertanker’s hull. He knows that he’s crossing the ocean between subject and object. He’s a commodity now, something for sale.

Whereas Jackson’s Kong at his most depressed hasn’t even left the island. Perched on his mountain throne at sunset—sighing, exhausted—he surveys the limits of his world, this green, teeming jungle of would-be successors. His weariness is existential. This Kong knows his Descartes. Before he’s ever taken into captivity, we’re let off the hook.

Kong ’76 refuses to absolve us. Filling in for the odious Driscoll is Jack Prescott, a Princeton paleontologist who sneaks aboard the ship (traditional routes to tenure include discovering a new species). Wilson suspects that his stowaway (Jeff Bridges) is either a spy from Gulf or Exxon, or a hippy radical plotting to thwart the corporation—he does have long hair and a beard—but a background check confirms Prescott’s academic credentials. Look closely at the wire Wilson receives and you’ll see that Prescott was a lieutenant in the U.S. Navy. Nevermind the implausibility of Bridges, 25 at the time, as a character old enough to have served in Vietnam, complete his doctorate, and publish two books. The point is that the military-industrial machine has sucked him dry too. Nevertheless, this doesn’t indemnify Prescott’s white liberal ass. Professors have often been big-game hunters of sorts. The zoos of this country, but also the museums and the textbooks display the trophies. By the time Prescott backs out of his deal as Petrox’s offical wrangler, and donates his fee to PETA, his complicity is already sealed.

“’Twas beauty that killed the beast.” The ’76 script forgoes Denham’s famous last line, which presumably would have gone to Wilson if Kong hadn’t trampled him back at Petrox’s unveiling ceremony. Guillermin ends with Bridges searching for Lange in a sea of tabloid photographers and rubber necks circling the dead gorilla. Out of nowhere, New York City’s mayor leaps into the frame in a tux, grabs the blonde, and smiles for the cameras. Jack stops in his tracks. The flashes continue to go off on Lange’s teary face. Abruptly, the whole mood is off-center. As in a Brian de Palma movie, an emotional rug’s liable to be pulled. Then we realize why Jack has frozen: triumph has upstaged tragedy. Beauty has been granted her wish. She’s a star. Is everybody crying?

Meghan O’Rourke argued in a recent Slate article that only Jackson’s King Kong delivers a “plausible” beauty-and-the beast love story. The earlier versions, O’Rourke writes, were “a form of mass misreading that appears to be a textbook case of (no pun intended) projection: By the film’s end, we feel sympathy for Kong, and we suspect that Ann Darrow must be aroused by his, er, performance, so we impute our feelings to her.”

Meghan O’Rourke argued in a recent Slate article that only Jackson’s King Kong delivers a “plausible” beauty-and-the beast love story. The earlier versions, O’Rourke writes, were “a form of mass misreading that appears to be a textbook case of (no pun intended) projection: By the film’s end, we feel sympathy for Kong, and we suspect that Ann Darrow must be aroused by his, er, performance, so we impute our feelings to her.”

To an extent, this is true. The big guy clearly repulsed Fay Wray, and with Kong ‘76 you get more dalliance than romance. Lange is smoldering in her debut turn as Dwan, the spacey vamp who wants to get into the movies (she changed her name from Dawn, to make it “more memorable”). This is after all Lange’s break too. Her “Dwan is so innocently corrupt she’s as childlike as Kong himself,” Pauline Kael wrote in her New Yorker review. Her “infantilism gives the picture a sexual chemistry that the moviemakers couldn’t have completely planned—some of it just has to be luck.” I couldn’t register at four how hot it all was for Lange to run and be chased, to pound her fists and holler and then be stroked, but I now recognize that on that day at the Cooper thirty years ago, Dwan’s mixed emotions were not necessarily that different from the desire and fear yoking me to my colossal father.

As my mom ran to the Cooper in those days, so did he scurry into that basement I liked to play in, where I suppose it was his lair too. He kept a portable TV in a room down there, and black iron weights the radius of car tires. They clanked like old radiators when he hoisted them on his barbell. Later, after the divorce, my dad would compete as an amateur body builder, but he was already gargantuan. Clothes rarely fit him right, especially shirts, which pinched him around the collar. He couldn’t wear a necktie without fidgeting. On the walls of his basement gym were posters of the bikinied sand-kickers he emulated, and as a consequence Ferrigno and Schwarzenegger were names familiar to me by kindergarten.

Kong never hurts the blonde, and let me be clear––despite his power and temper, my father never hit me, though he was awful intimidating. Sometimes when I interrupted his workout, we’d lie together on the floor and watch TV, but more often he was ticked. Other times, he wouldn’t shout or say anything at all if I disturbed him, he’d just look at me like I’d done something that reminded him of my mother. That was worse. I feel stupid comparing my father to a giant ape, and even stupider that that makes me the blonde, but as surely as Dwan, I faced the task of reconciling dread with love in that basement. Neither of us, Dwan or me, was particularly faithful. When the curtain falls, she’ll be looking for the nearest dotted line. And I haven’t seen my father in more than twenty years.

Kong never hurts the blonde, and let me be clear––despite his power and temper, my father never hit me, though he was awful intimidating. Sometimes when I interrupted his workout, we’d lie together on the floor and watch TV, but more often he was ticked. Other times, he wouldn’t shout or say anything at all if I disturbed him, he’d just look at me like I’d done something that reminded him of my mother. That was worse. I feel stupid comparing my father to a giant ape, and even stupider that that makes me the blonde, but as surely as Dwan, I faced the task of reconciling dread with love in that basement. Neither of us, Dwan or me, was particularly faithful. When the curtain falls, she’ll be looking for the nearest dotted line. And I haven’t seen my father in more than twenty years.

Kong isn’t strictly a mnemonic charge for me, he’s a measure of scale. He has determined variously the relative size of things: movie theaters, houses, a father. Also, skyscrapers. De Laurentiis’s intention in pushing the story forward in time was not to make King Kong ’76 more topical, although inadvertently that’s what he accomplished (Jackson’s version is the first to underwhelm the ledger, and the first not to be contemporaneous with its audience). De Laurentiis wanted a big finale, and he planned to stage the last battle on top of the newly constructed World Trade Center site rather than the Empire State building (at the time, no longer Manhattan’s tallest structure). Kong goes looking for asylum above these two steel dicks because they remind him of a similar rock formation on Skull Island. He’s trying, in other words, to get home.

For the last fifteen years, off and on, I’ve made New York my home, and I wonder if before they were destroyed those towers weren’t calling me. When we are children, does anything so violently chip away that first soft chunk of our innocence as the sudden knowledge of impermanence? I’m stuck with Kong, and he’ll stay with me my entire life, paradoxically because he taught me that nothing else will.