Interview with Peter Sotos

19.01.06

This interview originally appeared, in a slightly truncated form, in The Prague Literary Review Issue 4

This interview originally appeared, in a slightly truncated form, in The Prague Literary Review Issue 4

Bataille, Genet, Sade and company do swift business at the local bookshop, but some of the most adventurous readers I know tell me they haven’t gotten around to Peter Sotos. Distance renders depravity digestible, so cast the burly Chicago author in terms of his precursors––imagine Sade slopping through Chicago gloryholes; Bataille looping the audio of murderers, victims, and media whores into powerful sonic whirlpools; Genet diligently clipping/fleshing out/resuscitating news stories about child abductions (and abductors). Another turn-off to some: His books aren’t novelistic (and he doesn’t intend for them to be); instead, frame each as an ethics course steeped in cum shots and crime sprees. And for newbies, the texts are, in his words, "severely connected," i.e. the more you read, the more complex the repetitions, shadows, echoes, reverberations.

Sotos’ personal history also threatens to obscure his work. Because of the insistence on a narrative first person, he’s been vilified as a misanthropic pedophile. (His mid-80s kiddie-porn arrest for the possession of the zine, Incest #4, is often what folks know about the author.) Due to his history with seminal noise group Whitehouse, some view him as a part-time writer. Regardless, Sotos continually proves himself a rigorous thinker (sentences shot through with Nietzschean quivers) whose brutally spare prose and complex inquiries into desire make him one of a handful of contemporary authors justifiably worth their "transgressive" salt.

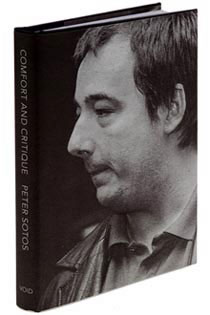

As of late there’s been a lot of activity surrounding Peter. Creation books published Proxy, a collection of books from 1991-2000: Along with Tool, Index, Special, Lazy, and Tick, it includes a cut-n-paste introduction by the author and a collagist CD (w/ Steve Albini). Last year Brooklyn-based Void Books published Selfish, Little and more recently made available Sotos’ strongest work to date, Comfort & Critique. Creation recently published Predicate: The Dunblane Massacre, Ten Years After (and, in fact, parts of this discussion show up in Waitress, released by Creation Books as a limited-edition accompaniment to other Predicate pre-orders). He edited and wrote the introduction for Jamie Gillis’ Pure Filth, out on Feral House in October 2006.

Comfort & Critique looks at, among other things, the 2000 abduction and subsequent murder of 8-year old Sarah Payne by prior sex-offender Roy Whiting in Sussex, weaving-in the author’s everyday discussions about soup, Annabel Chong’s The World’s Biggest Gang Bang (Chong fucked 251 guys in 10 hours), the "Name and Shame" riots in Paulsgrove UK (at one point a pediatrician was attacked when locals misread a sign). Check out also its play on timelines and Wordsworth’s child to the man (vice versa), etc.

I interviewed Peter Sotos this past summer. Since then, we’ve kept in touch, most often about music. There’s the temptation to say something nice about the notorious author, but instead of selling you on Peter the person (admittedly a great guy to get drunk with while discussing the finer points of Shellac), why not read his responses in the following interview and formulate your own opinion.

FANZINE: Perhaps an odd place to begin, but how do you support yourself?

FANZINE: Perhaps an odd place to begin, but how do you support yourself?

Peter Sotos: I work. Not that I think it’s such a good idea, but I always have. I don’t have a career. I do think it’s important that the books have no great commercial requirements and that my work isn’t split between lesser and greater degrees of seriousness — especially in regards as to who releases the material.

FANZINE: Any writing rituals?

PS: People sometimes ask if I write when I’m drunk. I do, sometimes, but it tends to get thrown out pretty quickly when I read it back sober.

FANZINE: Do you ever catch yourself writing for your audience?

Peter Sotos: I’ve heard how wrong I am for as long as I’ve been alive, it seems. So I have to weigh a possible audience’s possible arguments against mine all the time. But I don’t pander.

FANZINE: Where do you see yourself fitting in terms of literary tradition?

PS: I know where others say they see me fitting in. But, honestly, I don’t think in those terms at all. I don’t see anyone else doing what I do. Which sounds terrible, I know. But I don’t feel much kinship with contemporary writers, especially those who create fiction. My interest is in completely the other direction. There are writers whose work I love, of course, and it’s nice when some people make certain smallish comparisons. Sade, Dworkin… But nothing in terms of an ongoing tradition.

FANZINE: You mention Andrea Dworkin often. People might find the two of you an odd pairing, but on some level I guess you seem to share a notion of the humanity of victims.

PS: I disagree. I think Andrea Dworkin cared very deeply about her words being more than that – just words. I’m certain that I do, as well. But we don’t see the frustrating impossibilities of that action in the same context or towards the same result.

FANZINE: Have you read (Samuel Delaney’s) Hogg?

PS: I’ve read Hogg, of course. I think it’s supposed to be like a Tom Of Finland cartoon and it doesn’t do all that much for me. I like Times Square Red, Times Square Blue and The Madman much more but I’m uneasy about so fucking many of the community conclusions and connective politics. I honestly don’t think they exist. I go to the same kind of places Mr. Delany does, or did, I don’t know, and I have very different experiences.

FANZINE: When I think of contemporaries, I also pause at William Vollmann. But you’ve been critical of him and his work.

PS: I’m not convinced. He sounds untouched. A bad liar with quaint reasoning. We’re looking for different things, though. I don’t feel I have anything in common with such traditional concern.

FANZINE: People have referred to your books as formless, though there are obviously internal structures and connective patterns. How do you map the texts?

PS: I write what I like and connect the underlying themes and strains later. See what comes through, basically. Tick had a very clear numbering system running through it. Selfish, Little had a fairly rigid template. I suppose Comfort & Critique, though, has the most structure in that the news clips were very carefully selected and then placed in a very specific order. The book itself then came from that order and the general assumption that created it.

FANZINE: Proxy makes your self-sampling more explicit. Do you have an overall climax in sight?

FANZINE: Proxy makes your self-sampling more explicit. Do you have an overall climax in sight?

PS: No. But Proxy was designed, in large part, to draw out specific degenerative repetitions. That’s exactly why the books aren’t in chronological order. The last three books are presented as going backwards and the first two books are, sort-of, the index. The introduction is made of excerpts from newer unpublished material constantly concerned with how most of the sex joints and expectations are gone or dying fucking badly. But it’s not a narrative, you know?

FANZINE: Was its two-column newspaper-style layout intentional?

PS: Probably not. It might be something that both Jim Goad––when he published Total Abuse––and James Williamson from Creation had in mind, though. I’m far more interested in the text being like a book than a newspaper. I’m responsible for the layouts of Pure and Parasite, but not the books. The images are mine, though. I don’t try to comment on newspaper and media hypocrisy, I’m just largely unable to get away from it.

FANZINE: In Comfort & Critique you write, "I’m absolutely sick of the differences between intention and interpretation. I want to create an art that is ideally shored. One that can’t be misunderstood any longer. Not by the powers that want to see me jailed or by the fucking mice that pretend I’m doing something socially significant." How do you intend to make this happen?

PS: The work can only be done as writing. Where one sentence explains the one before it. Full length books. I’ve seen the questions I bark out used out of context and sold as something else, something less. I want to make sure the answers are rigorously considered and that can only be done by writing books, not creating advertising. I don’t have a blog or a e-commerce website.

FANZINE: What is it about the question and answer format and interrogation that lends itself to your project? And often, there’s often a noticeable disjunction between the question and the response.

PS: There’s some disjoint in the careful wording of the questions themselves. The way the questioner tells the answerer how to think isn’t subtle but still, almost always, almost naturally, accepted. Of course, there is my own internal dialogue at work, often enough, that finds focus and excitement in the way others pose and answer highly personal, as well as grossly impersonal, questions. That search for so-called brutal truth that is vain and badly done. The way cops and artists come off exactly like street corner faggots asking toothless hustlers if they’re cold without coats. The way that it can keep getting worse. The idea that others may know what’s best for you. May want to protect you and need to explain that to you. There’s quite a few reasons.

FANZINE: When did you meet Jamie Gillis?

PS: I met him in SF about six years ago, I guess. David Aaron Clark suggested it, originally. Jamie, as I see him, is exactly the rare sort-of person who understands the Q & A dynamic. He looks to me as if he genuinely wants to understand why these people, himself especially, do these things, these acts. Or want to see them. He asks legitimate questions and can’t be blamed for the bad answers of the participants. Or the low expectations of his audience. I do absolutely think he’d like to get more than type.

FANZINE: In Comfort & Critique, you write about the press defining victims, but the narrator also makes it known that he is not "blaming the parents or the other particulars or suggesting something about the nature of the press." Still, there seems to be a hazy area where such a critique pops up.

FANZINE: In Comfort & Critique, you write about the press defining victims, but the narrator also makes it known that he is not "blaming the parents or the other particulars or suggesting something about the nature of the press." Still, there seems to be a hazy area where such a critique pops up.

PS: Such a critique of the press or the general media just seems obvious to me. You don’t get news reports that are devoid of spin and you don’t get news reporters who don’t wink at you because of that. So critiquing the nature of the press seems redundant and unimportant. There’s a huge market for such examinations, especially in music and film, but it doesn’t mean all that much to me. I’m far more interested in how that thinking creates the bodies and personalities it reports on. To be precise, and use the quotes you pull, Sara Payne gradually became the product that the news wanted. Or, at least, the side I’m sold. But not as a concentrated and conscious marketing ploy. Rather as someone, emotionally reduced or not, might respond to comfort and attention, sympathy and flattery, incredible existential and physical loss. It’s similar to what most people might say they want in a relationship. I’m not just saying that the press is lying.

FANZINE: Reading Comfort & Critique, there are these multiple levels and philosophical moments. "Critique" has a didactic ring: Is it a philosophy of ethics in the sense of what Foucault was investigating when he died? I also kept thinking of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

PS: The title Comfort & Critique, essentially but not exclusively, refers to a simple journalism construct. Or pretense. The writers who concern themselves with Sara and Michael Payne, for example, who critique the situation, dispatch the news but shave any edges off so that the parents are constantly comforted and cared for. Whether they do this in obligation to their careers or a greater, perhaps humanist, ideal is incidental to my discourse. Of course, the bits you highlight connect this tendency to art. That most art, literature, music, journalism is blurred by a selfish interest in earning a living isn’t surprising. What is surprising is that these artists pretend that they’re offering an objective honesty. But, actually, I’m more interested in how that fluidity seeps into concepts of respect, love, sympathy, etc; personal and otherwise. Also the way that these journalists write so that they directly address the parents and the criminal at the same time. I understand the Wittgenstein and Foucault references in that they were trying to develop a systemic accuracy, a specificity; that is certainly a personal need of mine.

FANZINE: In the book there’s a vacillation between needing/not needing the photos of these children and the mention of needing only the "quickest trigger." Why did you decide to include the images at the end of the book? Is this what Sarah would’ve looked like?

PS: They’re the images that provoked the idea of Sarah. The idea of a magazine came from my wanting to compile these scraps and make something more complete, something better, than the purely functional way they were being personally handled just before. The magazine wouldn’t have been adequate. The only way to do what I wanted was to write this book about the impulse.

FANZINE: You mention that "Sara Payne should know about this book." Has there ever been an instance where a subject (or subject’s family) contact you about your work?

PS: That quote directly refers to Ian Brady’s book. I said that she should know about that book specifically because she had written an open letter to the “kidnapper” of Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman. She was offering a plea to the would-be killer. She was seriously out of her element, advice-wise, but definitely in her element public-wise.

FANZINE: Recently, you did readings in France in front of various still images: abducted children, television news, etc. I’ve seen a few of the CD-ROMs from where these images were pulled. Are they specifically companions to Comfort & Critique?

FANZINE: Recently, you did readings in France in front of various still images: abducted children, television news, etc. I’ve seen a few of the CD-ROMs from where these images were pulled. Are they specifically companions to Comfort & Critique?

PS: The films you saw were actually companions to the book that had just been released in France–Au Fait, which is a translation of Tick. I have quite a few of those badly edited collections, I tend to call it a system, and they apply to any work I’ve done. They inform the books but they shouldn’t be seen as anything complete. I struggled a great deal with explaining their personal context in France.

FANZINE: Why is the textual portion of the book named after Katrina Kassel?

PS: If there is a reissue of the book––without the photos––then I wouldn’t include that title. This is something I’d like to see in the future. But this edition is a necessarily small amount without any legal haggling or concern. That’s why the photos are included and why the print number is so small. Katrina and Sarah were names that I thought the original information could come wrapped in. The text functions in much the same way as the photos do. And I think Katrina Kassel is an extremely important subject in Sarah Payne’s short life and Sara and Michael’s longer one.

FANZINE: In the book, you posit a working definition of pornography: "It’s that severe but specific reduction that creates the definition of pornography…. It is purely what I do to an image. Or a fucking act that I only run through my head. It is the limitations you accept…"

PS: It’s impossible to apply grand definitions to pornography because the intense precision of individual taste is central. This is why laws and the necessary text on pornography are so loud and popular. It allows different sides to establish self-serving moral grounds but never a concrete or unified answer. One defines pornography for oneself only. The act of masturbation wouldn’t, obviously, qualify everything as pornography but rather what one is looking for in pornography. Just that these objects are capable of being used as pornography. I’ve seen far too much of this so-called "transgressive" pornography that is completely defined by the ridiculous arguments of those who seek to vilify printed words and pictures. The ones that bask in their naked freedom and flaunted spirituality are just as ugly, just as obscene, as the ones who constantly beg you to watch out for their children’s future.

FANZINE: Toward the end of Comfort & Critique there’s the hysteria at Paulsgrove and the idea that perhaps Roy Whiting didn’t fuck Sarah. I don’t feel like you need to humanize the predators because they already feel human to me. Was that your intention when you introduced this information into the book?

PS: No. Not at all. I think it’s important to understand that he probably didn’t fuck her not because it makes him a more human or conflicted soul but because it defines what little he may have wanted.

FANZINE: In the book you also write: "see if you can title it without making a headline about the havoc of loss and the strength that rises from despair." Is Comfort & Critique an attempt at that headline?

PS: Yes, in a much larger sense, I think it is.

FANZINE: Comfort & Critique features your most literary finale to date. The end ostensibly ties things together. It feels germinal and even elegiac. When it drops, you suddenly realize the dates have been going backwards and here’s your opportunity to look again at the book from end to start…

FANZINE: Comfort & Critique features your most literary finale to date. The end ostensibly ties things together. It feels germinal and even elegiac. When it drops, you suddenly realize the dates have been going backwards and here’s your opportunity to look again at the book from end to start…

PS: The structure is for me. I’m not playing a game whereby the reader may or may not get the information at hand. I’m not including a surprise or something that may be obscure. The template runs that way because I deal with that material constantly. I understood what was happening with the way I read and keep and consider all that material. It was the way I thought of the people turned down into flat material and my suspicions and tastes were born out in the text. I see the way these people change and mold but I’m unconvinced that they acknowledge it. Not in the sense that it defies the incredible trauma that they’ve suffered but instead that they might be reverting to type. There’s also an element of where you’re allowed to dip into the middle of their lives and work backwards from the public associations and shaky philosophies.

FANZINE: Speaking of which, why have you included the following quotes? "I do not want to fuck the child. Let that be the theme that glues everything together," "I’ve always imagined myself fully clothed with these children," and "the fantasy has to be built around children because the impossibility and all the lesser excuses wouldn’t be possible any other way." Is it an attempt to complicate the notion of memoir?

PS: I don’t put myself in someone else’s mind. If a public wants to see me as torturing someone then they can understand that the work is in the field of words on paper. I don’t pretend that there aren’t complications and responsibilities. Intention and satisfaction and complicity and tristesse; there are many that seek to tangibly superimpose these concepts onto the meta-physical. I understand, I hope, the limitations and incredible frustrations of language. I desperately try to break that down. There’s that part at the beginning of Comfort & Critique where I address the issue of police releasing carefully cropped sections of child porn in efforts to locate missing and endangered children. The way those in glory hole situations or anonymous sex backrooms try to connect to larger comfort and acceptance drives. The whole of Predicate, which is about Thomas Hamilton, is a personal history of just photos.

FANZINE: Sara Payne is presented as repetition. You also talk of your own repetitions: "Stop repeating yourself. Stop masturbating onto just photos and pretending it’s better than what the rest of the slime don’t even do," "I’m not that hard to figure out. Especially when I’m repeating myself." Can you imagine ever writing different sorts of books than the ones you have and are writing?

PS: I don’t write just to have a book with my name on it. I write because I’m compelled by the intensity, as well as the lack, in the material at hand. I think there’s a huge difference in the way I write now and what I’m better known for writing, but I see absolutely no reason to look for a subject to write about or find something I can somehow turn into a book or whatnot. I don’t look for new projects or ways to impress or surprise others. I’m not interested in craft. If I’m told I write well, I know that it comes from a passion with the subject. The subject propels the writing and the constant thought. I don’t have a need to create something. I have a need to create this.

You can purchase Comfort & Critique from Void Books.