Smithereens: On Robert Walser’s Microscripts

13.07.15

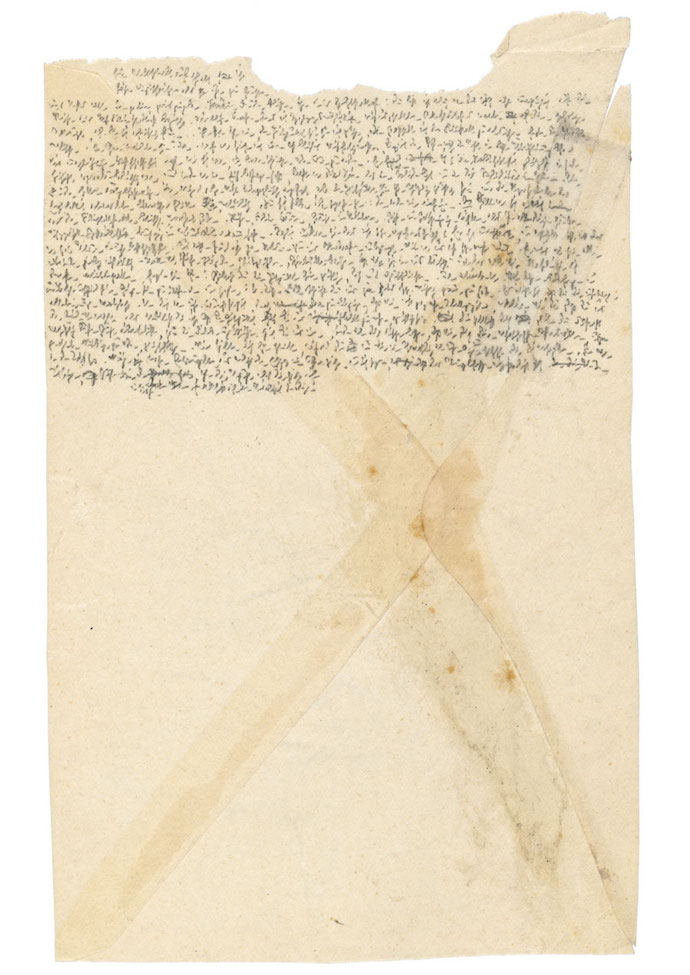

Where no additional space exists, the best way to make space is to shrink the occupying object. Where you cannot stretch confines, you make room by condensing that which is confined. This process of micromanagement can reveal arcades and vaulted ceilings in the details of a tomb. But having performed this act of dimunition, why then restrict the shrunken form’s working area? Why cut and tear away at those spaces made larger through shrinkage? Why make space only to unmake it? But this dimensional insecurity, this shift in being – from claustrophobia to agoraphobia – is really just part of the overall process of self-imposed restriction. First the person is reduced, then the world he inhabits.

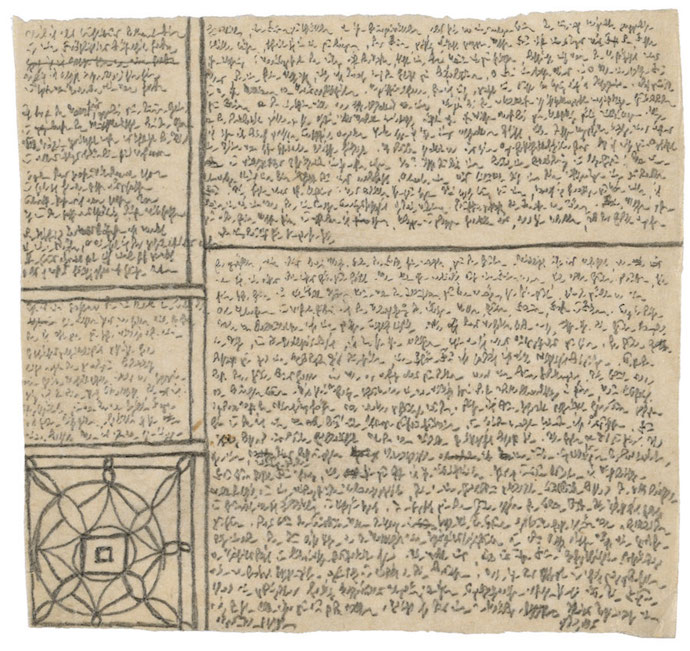

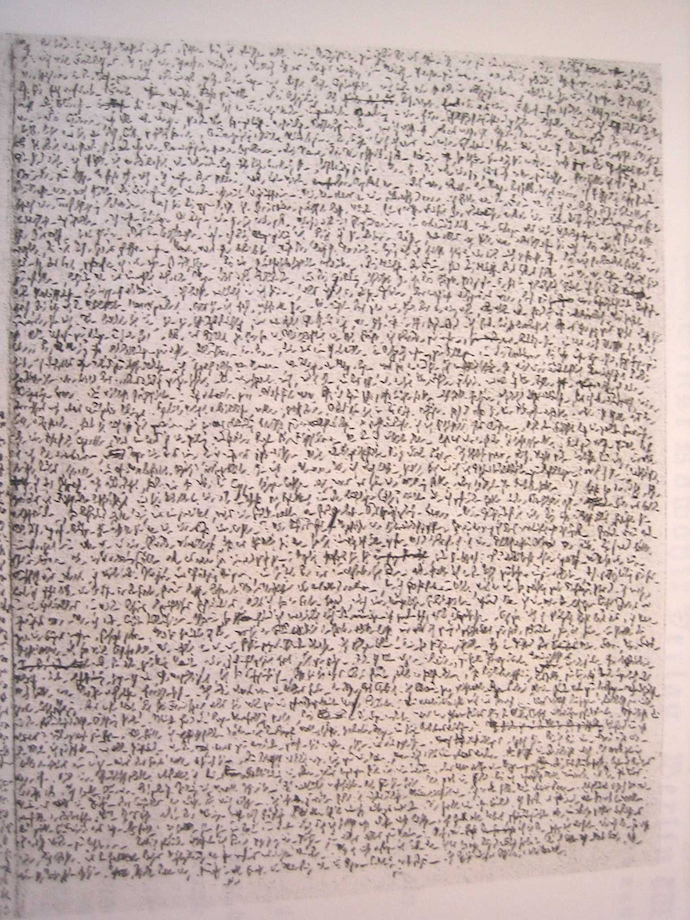

Walser’s choice of spaces is significant: the occupations he effects with his accelerated deployment of cramped insectile markings – coagulating into blocks of blurred uniformity – are scratched for the most part into dead spaces, flat holes obscured by illegible characters desperate to fill the space they created when they shrank themselves. These are spaces resigned to emptiness, spaces abandoned to the meaning-void eye-sleep of a single uniform tone, spaces made up of blank frames and the undersides of business cards (spaces homaging commerce), of used postal wrapping and envelopes (quietly militating against the importance of destination), of the hidden underside of a penny dreadful cover (regurgitating sensation as a small patch of swamp mould crawling along the bottom of a soiled blankness), of pages torn and dissected from glossy lifestyle magazines (where men like hogs are butchered for their choicest cuts), or of the backs of old calendar dates (detailing the return of the past in the insulated creatures of routine).

The characters, for all their elegant observations and pseudo-clinical diagnoses, disclose themselves like persons meticulously partitioned from the world, incomplete and fractured zombies devoid of the tools necessary to achieve genuine emotive residence, those irrevocably detached from certain standard human conditionings: back in the world like curios exhaled from an electroconvulsive therapy ward, reconditioned casualties declared fixed following programmes of highly-selective neuron annihilations. His people talk over the silence of themselves. Like lonely residents in a nursing home, they relate facts and empirical data for the sheer honest and healthy wonder of it – the listener (and the teller to some extent: “My activity is superior to me”) [i] is an irrelevance.

As to the genesis of Walser’s fictional figures, Walter Benjamin pinpoints a single source:

“his favourite characters come from […] insanity and nowhere else. They are figures who have left madness behind them, and this is why they are marked by such a consistently heartrending, inhuman superficiality. If we were to attempt to sum up in a single phrase the delightful yet also uncanny element in them, we would have to say: they have all been healed.”

The truth of this is plain, and once acknowledged profoundly felt, for only once we’ve realised what has happened to them and where they might have come from can we recognise how their success might be considered a crisis, their cheerfulness, and the cheerfulness of others, a sweetened suffering of the same pathology. Even the distractions of art and literature are regarded as essentially crisis-prone; and any contentment found, a progenitor of lament (verl-aCH). Walser’s ‘Demanding Fellow’ tells of how “the happiness he achieved was a sort of calamity,” so that he finds himself – with a painful sense of inevitability – sucked down into a condition in which “his longing, how he longed for it again.”

If we are to follow Benjamin’s appraisal, Walser’s characters have achieved what Gérard de Nerval and his ‘Aurelia’ could not: the latter being a story with which he intended to convince his custodian in Passy, Dr Blanche, of his impeccable sanity, his status as a cured man, a man at home in life and free of all but the threat of death. But ultimately the sharp line he sought to establish there, between the misery of madness and the happiness of health – the former replete with illusion and decayed senses, the latter with vigour and nourishment – was drawn too absolutely, the fabled ‘real world’ that he claimed to have finally accessed, too distorted by the sickness of longing and denial, his story lacking the matter-of-fact robotism of Walser’s.

The man in ‘Radio’ eavesdrops on a public broadcast, acutely conscious that the announcer, as he feels the need to point out, “had not an inkling of my listenership or even of my existence.” This interplay of intimacy and alienation, of being both included and ostracised, is typical of Walser’s conflicted instruments.

The outside world, exhaustively marked with history and human intention, is subjected to a tempered fuzzing, like when “interesting buildings that had played a role in history were mirrored in the still, color-suffused water of remote canals.” That narratology, that historiological grounding, made ever so slightly out of focus, like the appearance of the very script in which they struggle to breathe.

In ‘Swine’ we are asked, “Does not the endlessly endearing drag us down?” For there’s an interest in it all, loving and swinish – all the banal details laid out like jewels to be pondered in their natural state with no need for further embellishment. There’s an acceptance – a healthy one, maybe. This is what there is, let’s look at it. Let’s see it. Let’s attempt to see and for once not see-as. But this concentration engenders its own mysteries: an un-edited purity where narratives lay uncoupled and attentions shift. For this bleakness of happiness is a meandering state, so confusions are best left alone, as confusions. Where solutions are proffered they remain. They sit and exist as what they are: momentary reactions that were once in context. This way they seek to avoid the complications of truth and falsity. Where details muddy what goes on, they are omitted.

When in ‘The Train Station (II)’ there is talk of “useful money,” where the use of the extraneous adjective reveals a remoteness that is so explicitly contrived, and also when marvelling at the alien naivety of a comment like, “I myself am sometimes well-known, sometimes a stranger,” we are forced to confront the interspatial complexities realised by Walser’s cured narrators, how they are fundamentally disassociated not only from the world around them, but from themselves as encounterable things within that world. Like the microscopic scrawl that inhabits the space between the concrete of names, addresses and postal markings – some textual fungi or creeping vine leaching what life it can from flat, empty surfaces – his people are removed from those false (humanised) stories, and naturalised and haunting “sillinesses” reign in their place, something captured by James Joyce some 12 years earlier in 1920:

“When travelling you get into those waggons called railway coaches, which are behind the locomotive. This is done by opening a door and gently projecting into the compartment yourself and your valise. A man in an office will give you a piece of cardboard in exchange for some money. By looking at it attentively you will see the word Paris printed on it which is the name of this stop.” [ii]

Although “unable to feel at ease anywhere at all” (as is that foremost man), most of Walser’s people try desperately to exist ‘somewhere and somewhen’, and in the story underneath that title the best is seen as always missing, always nowhere and nowhen – a dream of the sick, bones dressed in a ragged couture of failing muscle and thinning skin, of airless places in which only words can breathe – “the present as the eye of God” in which men can only exist as a glossed reflection.

Walser’s disenfranchised onlookers (self-fleshed contraptions of iatric absence) can only see other androids, see their automated aimlessness, the terrifying and yet ridiculous automatism of their daily encounters, the one difference being that their existences have not yet been exorcised of the pleasure that makes the world sticky:

“People who are refined visit other refined people and confide in them, chattering and babbling out precisely what they have experienced and whether they found the experience indigestible or pleasing.”

In the revealingly titled ‘Usually I first put on a prose piece jacket’, the ease of transition from sillinesses to self-confessed horror suggests that there is nothing substantial keeping them apart, almost as if each were already encroaching on the other’s territory. The writer confesses that he hopes his automated prose piece “pleases you [the reader] so much it will make you tremble that it will be for you, in certain respects, a horrific piece of writing” But why horrific? Wherein lies the horror for a healthy mind? In the lines preceding this, we are told of the mechanistic gesture of a woman, Rosalinde, who in dispensing bread to an underling does so with a movement at once utterly machine-like and beautiful, like the gallop of a horse – an animal that runs through her like blood (for as we see with Mr Brown and Mrs Black, names colour Walser’s figures indelibly and all the way down). The horror, then, is in the juxtaposition of beauty and the machine, the essentially un-personed qualities of grace.

About ghosts, Kafka writes: “You’ll never get a straight answer out of them. Talk about vacillation! These ghosts seem to doubt their own existence even more than we do, which given their fragility is hardly surprising.” [iii] On this basis, all Walser’s figurines are bordering on the spectral: an ontological status befitting the almost wraithlike text that constitutes their true flesh.

The father and son shut up inside ‘Jaunts elegant in nature’ like trinkets in an oak display case, the wife and mother invisible but for youth, beauty and a legacy of curls (no trademark frustrations or shrewishness, no meat there “longing for viper bites”), present two opposing facets of man’s ailing health: the progenitor flattened and stripped of pulse by an overbearing sense of duty and stoicism – for although desires would surface, “he found it his duty to disregard them;” and when gripped by isolation and insomnia, “befriended loneliness” and the nights from which he could not remove himself – and his progeny, devoid of such concerns and so scarcely present at all, an alteration in air current, an olfactory pleasantry; too insubstantial a being to breed even the slightest of adversaries (“he was forbidden to become something to which breath and a form belonged”) and so never quite a man, his illness and subsequent death ushering him away like something (un-thing-like) becoming itself again, a ghost fading from view like some lightly-sketched portrait left out in the sun. (The son is not in the world, but neither is he in his own story – for “characters in books stand out better, I mean, more silhouettishly from one another, than do living figures, who, as they are alive and move about, tend to lack delineation.” He is instead a poetical hypothesis on the possibilities of corporeal minimalism, an exercise in existential subtraction.)

The residence of this faintly-realised son (blessed with not only his mother’s curls, but her figmental ontic status as well) is a place rich with alluring detail. But one detail is worth noting more than the others: “The air appeared to be the bride of the garden, and the garden its bridegroom.” That the second half of this sentence should have been thought requisite is itself something deserving of a book-length treatment, for it is not there by accident, and it is not mere pleonastic clutter. That a relation that is axiomatically two-way should be documented so comprehensively allows the reader to see the degree to which Walser’s worlds are atomized: no matter what the relation between objects and people they remain intrinsically separate, inassimilable entities that are somehow fundamentally remote. Even a man who would be a wretch, and who, enslaved by his desire, attaches himself to a woman who would make him one is not truly united with her, for even this seemingly harmonious reciprocity simmers with the imminent threat of rupture. Even the man who orates on the evils of schnapps is so distant from his words that he must do so while under its influence. And even though one’s own goodness may be considered contingent on others, that goodness is never duly transferred, but merely a requirement that leaves its subject empty. All are disconnected in a way that no brutality of kindness can alleviate, disengaged like the nun we find in the company of soldiers, or the city man persecuted in the quiet country village.

The robustness of Walser’s figures resides in their ability to accept the precipitous frangibility of human life. They are the ones who are no longer “too frail to disclose [their] own frailties,” the ones cracked and mended, those “strong at the broken places.” [iv] But what Walser compulsively details is the price of this strength: the ever-present uncertainties, the safety of a cold dead eye, the self-imposed strictures that are required in order to just approximate pleasure. Concerning the inception of the title for his most famous novel, William Burroughs writes: “I did not understand what the title meant until my recent recovery. The title means exactly what the words say: NAKED Lunch – a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.” [v] This is the aftermath of recovery, a state in which nothing is taken for granted, or glossed over, or just consumed – the world comes to these convalescents raw and unseasoned, no longer greased human for the palate. And happiness is no exception, its paradoxical nature haunting the microscripts: “the shakiest of things and yet also the most solid.” An observation illustrated by Kafka in his four-sentence story, ‘The trees’:

“For we are as treetrunks in the snow. They appear to lie flat on the surface, and with a little push one should be able to shift them. No, one cannot, for they are fixed firmly to the ground. But look, even that is mere appearance.” [vi]

Perhaps, though, the only place for victory and approbation, for completion and stability, is, as the “Cheib” of microscript 50 discovers,[vii] in a future into which we disappear to be remade in stone.

Walser’s people are trying to set up home in autumn, and to ignore the seasons that precede it. For autumn has rightly put aside the false promises and gibbering inanities of spring (it knows that “Not only under ground are the brains of men / Eaten by maggots”), [viii] and has shrugged off the glare of a summer that had its eyes squinting half-blind. It has confidence in a worse state, a darker, colder place, and so finds some solace there – if only in its postulation, as seen in Walser’s mansion-dwelling beggar who “was constantly taking his autumnalities for granted, as though there were such a thing as precisely nuanced gradations of life.” [ix] These demarcations are the stripes of their sanity. But habitation is never less than precarious, for though fortified those fortifications demand constant attention and renewal. A similarly anthropomorphic treatment of autumn can be found in the work of Georg Trakl, whose poems are haunted by the creeping manifestations of this starkly contemplative season. He could have been addressing Walser’s creations when he wrote: “More pious now, you know the meaning of the dark years, / The cold and autumn in lonely rooms,” [x] been commenting on their fragile happinesses when describing the “Autumn sun, thin and unpredictable,” [xi] or the inauguration of their perspectival insulation by warning that “When autumn arrives, / a sober brightness appears,” [xii] describing their new topography of “Bare trees in autumn and stillness,” [xiii] their status as peripheral autumnal stains, those “black footsteps on the edge of the forest.” [xiv]

The cartographer of facets and incidentals does not risk being consumed by the whole. The minutiae pile up like fragmented specimens on a shattered slide; incomplete and detached from its once rightful context, each takes on a new existence, one resisting the pain of conclusions and the demented dreams of completeness. The convalescent hides in the moment, languishes in a present that never completes, and in documenting it he documents himself: consciousness now stripped of the threat of any prolonged confrontation with itself. And so when the Blue Page-Boy says, “I have not yet ever experienced anything worth mentioning except that now and then, i.e., relatively seldom, I glance into a little mirror,” he has already indicated that the subsequent question, concerning whether or not he at some time kissed at a woman’s mouth through a spoon, might be best left hanging, his proposed informality with the questioner left perpetually unconsummated.

Mistrustful of life and the blind integrations of humanity, Walser’s characters, like his script, are instruments of precision used to perform localized surgeries, glass-eyed eviscerations of shrunken and necrotized anatomies, whereby the aggregate tissue of life is left nebulous and alive: a mechanism of defence, for, as Cioran explains, while: “Depressions pay attention to life, they are the eyes of the devil, poisoned arrows which wound mortally any zest and love of life. Without them we know little, but with them, we cannot live.” [xv] Walser’s people have managed to isolate the poison, and are careful – a lifeless care – not to let it spread, to dissect life’s corpse into enough pieces that it may never be put back together.

The work is only worth it when it isn’t, like surgical precision honed on a corpse.

————

[i] Robert Walser. Microscripts (New Directions, 2010), 43. All quoted material from this text unless otherwise stated.

[ii] James Joyce in a letter to Frank Budgen.

[iii] Franz Kafka. ‘Unhappiness’ in Franz Kafka Stories 1904-1924. (Abacus, 1981), 41.

[iv] Ernest Hemingway. A Farewell to Arms (Scribner, 1997), 225.

[v] William Burroughs. Naked Lunch (Flamingo, 1993) 7.

[vi] Franz Kafka. Franz Kafka Stories 1904-1924. (Abacus, 1981), 37.

[vii] See: Robert Walser. Microscripts (New Directions, 2010), 65.

[viii] Edna St. Vincent Millay. ‘Spring’ in Second April (Kessinger Publishing, 2004), 2.

[ix] Robert Walser. Microscripts (New Directions, 2010), 89.

[x] Georg Trakl. ‘Childhood’ in Autumn Sonata (Moyer Bell, 1989), 77.

[xi] Georg Trakl. ‘Whispered in the Afternoon’ in Autumn Sonata (Moyer Bell, 1989), 43.

[xii] Georg Trakl. ‘Helian’ in Autumn Sonata (Moyer Bell, 1989), 67.

[xiii] Georg Trakl. ‘Sonja’ in Autumn Sonata (Moyer Bell, 1989), 97.

[xiv] Georg Trakl. ‘Transformation of Evil’ in Autumn Sonata (Moyer Bell, 1989), 125.

[xv] E. M. Cioran, from The Book of Delusions, trans. Camelia Elias in Hyperion, Volume V, issue 1, May 2010, 75.

This essay previously appeared in print in the UK in The Black Herald.