Semiotics—not just for the French!: A Review of Jennifer Kronovet’s The Wug Test

12.01.17

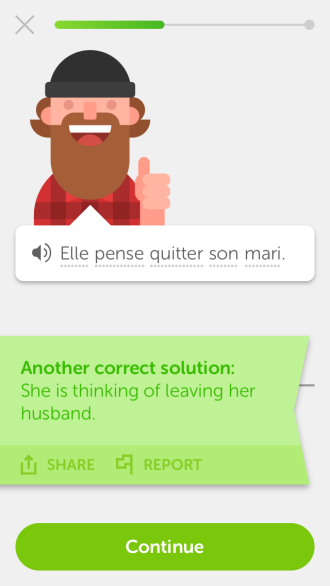

Recently, in an effort to “better myself,” I downloaded DuoLingo, the popular language-learning app—I thought I might brush up on my French. DuoLingo teaches languages by gamifying them. Here’s how it works: users tackle lessons on vocabulary (“Food,” “Animals,” “Idioms,”) and grammar (“Adverbs,” “Pronouns,” “Past Imperfect”) through a series of exercises—word-matchings, fill-in-the-blanks, sentence translations—earning “experience points” along the way. The first few lessons are simple. You learn to say “tomato,” and “shark,” and “hat.” You learn past and future tenses. Simple translations, like “It is raining,” or, “Do you read the newspaper?”

It gets dull after a while. But as the user improves, the app starts generating more complex sentences. Soon, micro-narratives emerge. Fragments of stories much more compelling than any multiple choice question. You might be asked to translate a sentence like, “He used to be respected by everyone.” “She was no longer loved by her husband.” “In this village, it is impossible to build houses.” Suddenly, what was once automated and rote becomes human and personal. You want to know what this man did to lose everyone’s respect. You want to know where this woman’s marriage went wrong. And what’s up with the development freeze in this village?

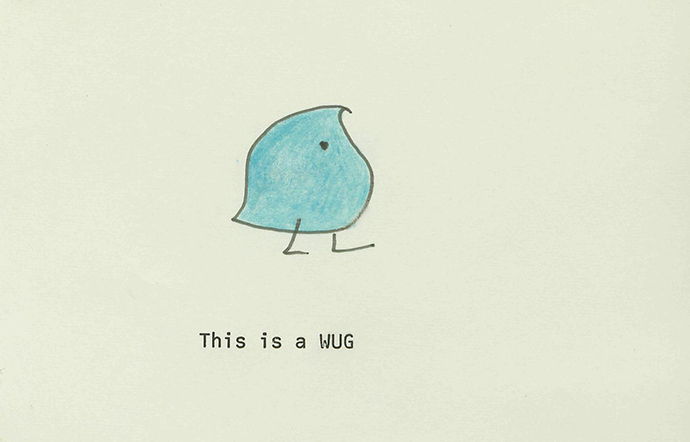

The Wug Test (Ecco), the second collection of poems by Jennifer Kronovet, inhabits this very intersection of linguistic rules and their active role in our lives. Kronovet’s project—she is a translator as well as a poet—is to strike the corpse of philology with a lightning bolt and bring it back to life; to show us why the rules we follow in our speech and writing matter. The “Notes” section at the end of the book reads like a Who’s Who of linguistics and semiotics: Jean Berko Gleason, Charles K. Bliss, Benjamin Lee Whorf, Ferdinand de Saussure. But The Wug Test is anything but dry or academic. It’s a playful, exuberant trip through linguistic theory.

Many of the poems are narrative, and read like micro-fables set in worlds as hazy and imprecise as the words used to describe them. In “Idioms,” a father implores his daughter to “remove the word from the thing”—she becomes afflicted with Hovering Language Syndrome. In “Phonetics: S, A Love Story,” a character’s /s/ has “a slight echo or whistling sound…she pronounced herself as herself.” Gender, and the idea of gendered language, inspire some of the collection’s best lines, as in “Semantic Analysis: Beauty”: “Men are 20% worse at using beauty than women.” In “English Female Speech,” an authoritative voice instructs the reader: “Do not break the plate and say please at the same time.” High theory is always tempered with humor. Perhaps no line encapsulates Kronovet’s tone better than this one: “Language shapes experience and kaboom.”

Mothers and sons also feature prominently in The Wug Test. A series of poems concerning a character referred to as “the boy” present a mother re-learning language through the experience of parenting, freshly aware of how words shape both of their experiences: “I feed him while concentrating on the words / I feed him. (If I list them, we might fail.)” Elsewhere, in another of the boy-poems: “We use words like a tree uses light: / there is a process we don’t see but do.” In another, after reflecting on Chomsky’s Language Acquisition Device theory, the speaker can’t help but “see them, the children, processing.” She “can’t undo the device to / make them less machine.” This anxiety, that every word a child is exposed to will shape them, however imperceptibly, permeates The Wug Test, tempering the playfulness of other poems. Kronovet gives new meaning to—and has fun with—the phrase, “mother tongue.”

These “other poems” frequently open with a premise, or a hypothesis—“Each language brings new words in differently,” or “It is well studied why it is developmentally important for children / to ask approximately three hundred questions a day”—before testing the premise. But somewhere along the line the test goes deliberately awry, language breaks down—an explosion in the laboratory—and the reader is left to sort through the debris.

Elsewhere, the poems don’t test theories so much as humanize them. In “Critical Period Hypothesis,” Kronovet invokes the real-life case of Victor, ‘The Wild Boy of Aveyron,’ a feral child who “left the forest and became evidence.” In Kronovet’s poem, based on the true case study, Victor loves milk but doesn’t know how to ask for it. He exclaims, “Milk!” only when it’s put in front of him, a reminder that “we must keep one another inside our words.” A story like this seems made for Kronovet. The Wug Test is a delightful book, as fun as it is intelligent, by a poet who sees “words as milk” and whose “mind survives on language.”