Save The Receipt: Rethinking Wes Anderson

17.10.07

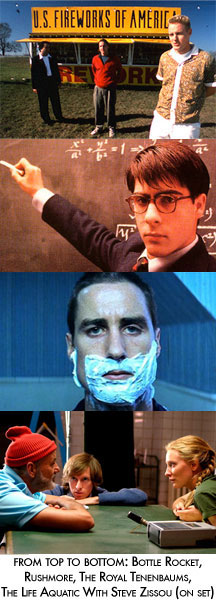

In 2006, Wes Anderson, weary and at the end of a long string of films that began with 1996’s Bottle Rocket, and proceeded through Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums and, most recently, the expensive and unevenly reviewed The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, made a commercial. In the ad, which was commissioned by American Express, Anderson himself is caught on set while directing a scene from a film that sharply resembles François Truffaut’s Day for Night—“Making movies: How do you do it? What’s it like?” he asks the camera. As Georges Delerue’s soundtrack saws away in the background, Anderson reviews props, meets a young fan, tweaks dialogue, admires an actress, and finally gets hit in the face by another cinematic allusion, a flock of birds. A $15,000 helicopter shot is too expensive, he’s told––a reference to his underfinanced second movie, Rushmore––so he reaches into his pocket, and hands over his wallet. “I got it,” he tells his producers: “Save the receipt.”

In 2006, Wes Anderson, weary and at the end of a long string of films that began with 1996’s Bottle Rocket, and proceeded through Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums and, most recently, the expensive and unevenly reviewed The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, made a commercial. In the ad, which was commissioned by American Express, Anderson himself is caught on set while directing a scene from a film that sharply resembles François Truffaut’s Day for Night—“Making movies: How do you do it? What’s it like?” he asks the camera. As Georges Delerue’s soundtrack saws away in the background, Anderson reviews props, meets a young fan, tweaks dialogue, admires an actress, and finally gets hit in the face by another cinematic allusion, a flock of birds. A $15,000 helicopter shot is too expensive, he’s told––a reference to his underfinanced second movie, Rushmore––so he reaches into his pocket, and hands over his wallet. “I got it,” he tells his producers: “Save the receipt.”

Wes Anderson grew up as the second of three brothers in a well-off family, and had the good fortune to attend the prestigious St John’s School, in Houston, a setting that would later inspire Rushmore. At the University of Texas, Anderson wore preppy L.L. Bean clothing, wrote short stories, and studied writing for the screen and stage. In one such class he met Owen Wilson, the aspiring writer and actor who would become the co-writer on his first three films, and who would star in all but one of them. After their first project together, a 1994 short that would eventually become Bottle Rocket, Anderson and Wilson sought both financial backing and work-for-hire in the film industry, but could not, in Anderson’s words, find employ: “We couldn’t get the rewrite job on a movie that wasn’t even going to get made.” This frustrating pause, however, would end quickly, and both Anderson and Wilson’s rise to success was unimpeded in the aftermath of Rushmore, which finally made Anderson a respected and somewhat bankable auteur and gave Wilson the confidence (and/or marketability) to pursue a lucrative acting career in Hollywood.

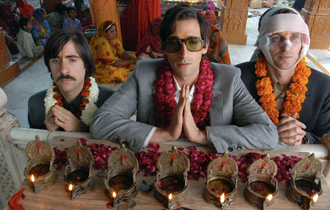

Through their mutual successes, their creative circle only broadened, and on Anderson’s newest film, The Darjeeling Limited, the writing credit Anderson had traditionally shared with Wilson was spread instead between himself, Francis Ford Coppola’s son, Roman, and Roman’s cousin, Jason Schwartzman. To make Darjeeling, which is set in India, and mostly on a train, Anderson, Schwartzman, and Coppola first lived much of the story out. “I guess we went to India as research,” Anderson told New York magazine, “but the more precise-slash-romanticized description would be that we were trying to do the movie, trying to act it out. We were trying to be the movie before it existed.” With Darjeeling, the fantasy of Anderson’s American Express commercial, in which money was no object and every detail was cinematic, became reality: Anderson’s life was his movie, his movie his life.

Through their mutual successes, their creative circle only broadened, and on Anderson’s newest film, The Darjeeling Limited, the writing credit Anderson had traditionally shared with Wilson was spread instead between himself, Francis Ford Coppola’s son, Roman, and Roman’s cousin, Jason Schwartzman. To make Darjeeling, which is set in India, and mostly on a train, Anderson, Schwartzman, and Coppola first lived much of the story out. “I guess we went to India as research,” Anderson told New York magazine, “but the more precise-slash-romanticized description would be that we were trying to do the movie, trying to act it out. We were trying to be the movie before it existed.” With Darjeeling, the fantasy of Anderson’s American Express commercial, in which money was no object and every detail was cinematic, became reality: Anderson’s life was his movie, his movie his life.

Critics reviewing Darjeeling picked up on the fantasy and wish-fulfillment aspects of Anderson’s film, and took the opportunity to critique him for it, going so far as to re-read each of his four previous films as steps in an obnoxious parade of precociousness and privilege. Darjeeling, a movie in which three obviously wealthy yet unemployed brothers go to India for the purpose of finding themselves over the course of a “spiritual journey”, was indicted for glorifying a kind of “vague, paralyzing, leisure-class malaise,” in the words of one reviewer, a glorification which demonstrated just how out of touch with reality Anderson was. Anderson’s agreed-upon greatest strength, his ability to frame a shot and to populate it with numerous beautiful details, was rephrased as an aggressive and thoughtless maneuver: “Beware,” said the same critic, “of any film in which an entire race and culture is turned into therapeutic scenery.”

Commented upon by both Anderson and his critics was the close social and spiritual connection between the director and the characters that populated his film. In addition to admitting that he had, with two surrogate brothers, acted out Darjeeling’s plot in the creative space of his own life, he also made the connection between the three brothers of his film and the two real-life brothers with whom he had grown up.

Further blurring the relation between Anderson’s fantasies and his reality was the suicide attempt, in the month leading up to the release of Darjeeling Limited, by his leading man, Owen Wilson. Audiences and critics alike saw queasy echoes in a scene late in the actual film, in which Owen Wilson’s character, Francis Whitman, shares a bathroom mirror with his two brothers, Jack and Peter. As the younger two look on, Francis strips off the maze of bandages that have encircled his face throughout the movie and, with some ceremony, reveals jagged scars beneath. In turn, this scene directly referenced one in The Royal Tenenbaums, which Owen Wilson co-wrote, in which Wilson’s real life brother Luke plants himself in front of a bathroom mirror and gives himself a haircut and a shave before turning the razor on his own wrists—the method Owen was rumored to have himself employed on August 26, 2007.

Further blurring the relation between Anderson’s fantasies and his reality was the suicide attempt, in the month leading up to the release of Darjeeling Limited, by his leading man, Owen Wilson. Audiences and critics alike saw queasy echoes in a scene late in the actual film, in which Owen Wilson’s character, Francis Whitman, shares a bathroom mirror with his two brothers, Jack and Peter. As the younger two look on, Francis strips off the maze of bandages that have encircled his face throughout the movie and, with some ceremony, reveals jagged scars beneath. In turn, this scene directly referenced one in The Royal Tenenbaums, which Owen Wilson co-wrote, in which Wilson’s real life brother Luke plants himself in front of a bathroom mirror and gives himself a haircut and a shave before turning the razor on his own wrists—the method Owen was rumored to have himself employed on August 26, 2007.

Though this tragedy could have been seen as validating Wes Anderson’s preoccupation with fictional characters whose advanced level of success and emotional problems closely mirrored those of a real life Owen Wilson––cares that turned out to be altogether too real––widespread knowledge of Wilson’s suicide attempt did not preempt the criticism that Anderson’s films were deficient for dwelling almost exclusively on the troubles and cares of white men with privilege and education.

When asked about this criticism by a New York interviewer, Anderson didn’t have much of a response, beyond denying that there was anything dishonest in his work: "Making movies to try to show everybody how great and cool we are…well, that’s just not the case," he told the magazine. "We’re trying our hardest to entertain people, to make something people will like, something people will connect with. I don’t think there’s a great effort to try to make some statement about ourselves, you know?"

In any case, Anderson’s minute attention towards characters of a certain fortunate background was hardly something he could deny; nor would he even want to. Rather his point, underscored by his friend’s suicide attempt, was that there was nothing wrong with––and in fact, something important about––investigating a specific type of upper-class and dissolute character onscreen. His work has carved out its unique space in modern American film for precisely this reason: no one cares more about this uniquely unsympathetic character than Wes Anderson, a fact that initially drew a tremendous audience of theatergoers who seemed to relate, to the tune of The Royal Tenenbaums‘ fifty million dollar box office return.

In any case, Anderson’s minute attention towards characters of a certain fortunate background was hardly something he could deny; nor would he even want to. Rather his point, underscored by his friend’s suicide attempt, was that there was nothing wrong with––and in fact, something important about––investigating a specific type of upper-class and dissolute character onscreen. His work has carved out its unique space in modern American film for precisely this reason: no one cares more about this uniquely unsympathetic character than Wes Anderson, a fact that initially drew a tremendous audience of theatergoers who seemed to relate, to the tune of The Royal Tenenbaums‘ fifty million dollar box office return.

Anderson’s subject, in that film as well as in those that followed, might best have been summarized as the problem of living well. In Darjeeling, the director’s response to the drab boredom, the yawning good fortune that the Whitman brothers represent makes a kind of sense: their life would be impossibly dull and conventional if they didn’t seek out the beautiful objects and outré adventures they do, even when these adventures turn out farcical or tragic. When Wilson, playing Francis, peels away his bandages in front his two brothers (Peter, played by Adrien Brody, and Jack, played by Jason Schwartzman), Peter’s response is to say: “Well, you’re going to have a lot of character to you.”

In Bottle Rocket the trio of main characters, who are middle class-to-rich, play at being gangsters; in Rushmore, Max Fisher, a motherless scholarship student at a posh boarding school, puts on elaborate plays. Anderson’s characters, with money or not, are constantly complicating their lives for the sake of making them more like fiction, or art—the vision Anderson would later make explicit while satirizing it on American Express’ dime.

In Bottle Rocket the trio of main characters, who are middle class-to-rich, play at being gangsters; in Rushmore, Max Fisher, a motherless scholarship student at a posh boarding school, puts on elaborate plays. Anderson’s characters, with money or not, are constantly complicating their lives for the sake of making them more like fiction, or art—the vision Anderson would later make explicit while satirizing it on American Express’ dime.

Parody has always been the way in which Anderson highlights the very real pain in his characters’ seemingly absurd facades. When the three brothers descend from the titular train that is the vehicle for their spiritual journey and mingle with the people, Francis has a $3,000 loafer stolen and yet declares, only minutes later, “I love it here—these people are beautiful.” Anderson mocks the oblivious sentiment even as he demonstrates something basic about Francis—that he longs for something he doesn’t have, namely a single real relationship with another human being.

Later, after the brothers have availed themselves of both the country’s train stewardesses and religious shrines as means for potential revelation, the natives on their train become so annoyed with the antics of the Whitman brothers that they’re thrown off their train, baggage and all. After wandering the desert sans amenities, and admitting spiritual defeat, the brothers happen upon three Indian children in the midst of drowning in a nearby river. They rescue two. “I didn’t save mine,” says Peter, and though his attitude is ridiculous, his guilt and horror are real. Anderson’s camera takes in the radiant whites, yellows, and blues of the bereaved family’s dwellings. As the mute brothers watch, the father bathes his dead son, washes him, and sends him off.

Asked about the way in which Anderson’s three brothers obviously make a fetish of the native people of India, Waris Ahluwalia––the Sikh actor who plays a train steward in Darjeeling, and who also had a supporting role in The Life Aquatic––told the New York Press: “We knew that was racist. It’s the character. It’s done to agitate Owen’s character.” He also noted the difference between Anderson and his characters: “Wes treated the country beautifully, in terms of how he shot it. It’s earnest and honest. The films of Satyajit Ray are something that he loves. He got really into it. So why is it fetishistic in a bad way? We all fetishize things. Maybe he did.”

Asked about the way in which Anderson’s three brothers obviously make a fetish of the native people of India, Waris Ahluwalia––the Sikh actor who plays a train steward in Darjeeling, and who also had a supporting role in The Life Aquatic––told the New York Press: “We knew that was racist. It’s the character. It’s done to agitate Owen’s character.” He also noted the difference between Anderson and his characters: “Wes treated the country beautifully, in terms of how he shot it. It’s earnest and honest. The films of Satyajit Ray are something that he loves. He got really into it. So why is it fetishistic in a bad way? We all fetishize things. Maybe he did.”

Anderson’s obsessive-compulsive compositions and information-soaked frames are often seen as trivializing what he puts inside them––such as the beautiful shots of the dead boy’s funeral––but one could also say the exact opposite. Darjeeling, like 2004’s The Life Aquatic, utilizes a continuous set, in which the camera is able to pan across each and every room of the train, in Darjeeling, and every chamber of Zissou’s boat, in Life Aquatic. As the camera scrolls through the train towards the end of Darjeeling, each compartment is occupied by one of the movie’s bit players––the Indian porters on the train, the Whitman brothers’ discarded assistant, etc––acting out a moment of their ongoing lives. Out of the camera’s eye, goes the idea, life continues. Anderson’s mania for detail extends to compassion for those crewmembers and actors he brings into his world, however briefly. They wouldn’t be there if he didn’t respect what they represented—aesthetically and intellectually, which for Anderson tend to be one and the same.

Francis’ challenge, early on to his brothers, is to “Say yes to anything.” This is the challenge to which his characters have been responding to since Bottle Rocket: the challenge (and the dream) of handing over the Am Ex for the sake of the film. The people who populate his films are often bad guys, because they can never refuse even their worse instincts, but in the end, this is also what allows them to become great.