Ignition, Orbit & Landfall: A Liars Synopsis

18.10.07

When we talk about a band’s “growth,” we often mean simply “change”: they’ve dropped or added a string section; they’ve traded rock percussion for disco. This sort of change is usually cosmetic and predicated on ideals of perfectibility. Different variables are slotted into the same fundamental equation, with a drive toward higher levels of listener-satisfaction, salability, or both. This sort of creative arc fits seamlessly into a commercial framework where we vote, with dollars, for quality products, and expect these products to accrue quantifiable value as they are refined over time. It’s as if a band’s first album is the beta test, and each subsequent album is a new iteration of the product that should minimize the failures and build on the successes of the last.

When we talk about a band’s “growth,” we often mean simply “change”: they’ve dropped or added a string section; they’ve traded rock percussion for disco. This sort of change is usually cosmetic and predicated on ideals of perfectibility. Different variables are slotted into the same fundamental equation, with a drive toward higher levels of listener-satisfaction, salability, or both. This sort of creative arc fits seamlessly into a commercial framework where we vote, with dollars, for quality products, and expect these products to accrue quantifiable value as they are refined over time. It’s as if a band’s first album is the beta test, and each subsequent album is a new iteration of the product that should minimize the failures and build on the successes of the last.

While Brooklyn expats Liars operate under the same commercial umbrella as their peers, they are of a different breed: when we talk about “growth” vis-à-vis Liars, we mean, quite literally, “growth.” This is a band who’s never come out of beta, who reinvent themselves album by album (flouting the continuity that’s so vital to packaging and selling bands), and whose musical quest is predicated on intuition and exploration, not perfection. Anarchism is traditionally anti-government, but in the United States this has become synonymous with being anti-commerce, and while Liars profess no outward ties to anarchist movements, their bullheaded resistance to institutionalized models of stability and crystallization places their albums among the most spiritually anarchic available commercially today. Their art is dangerous, often indigestible, and transcendentally inclined: each album has been a conceptual space where individuals meet each other, in a wildly specific moment with no history or future, to manifest something that embodies that hermetic moment.

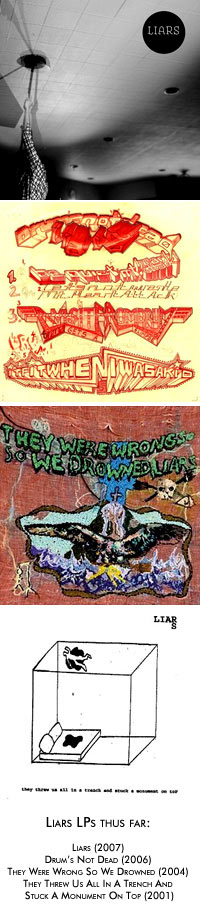

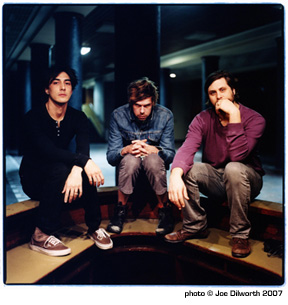

If this seems like a particularly good time to examine Liars’ creative arc, it’s because they’ve recently come full circle with their self-titled fourth LP, which finds the band completing their extraterrestrial orbit and landing in their own footprints. This sense of closure is amplified by the fact that band members Aaron Hemphill and Julian Gross have returned to California, where Liars first convened before moving to Brooklyn to make their names. An arc is all potential, but a ring offers us at least a temporary completion, and FANZINE checked in with Liars singer Angus Andrew by telephone to see how our intuitions about his band’s trajectory squared with reality. A native of Australia who now resides in Berlin, Andrew is genial and easy-going, which is belied by his imposing stature: imagine if you took Nick Cave and stretched him until he seemed about eleven feet tall, then put him in a gold lamé loincloth to grunt and howl over ceremonial percussion and paint-peeling feedback.

Liars arrived in New York City around the turn of the millennium, when “Brooklyn” was practically a genre unto itself. At this time, the band consisted of Andrew, Hemphill, bassist Pat Noecker and drummer Ron Albertson. In 2001, they released their debut, They Threw Us All in a Trench and Stuck a Monument on Top, on the Gern Blandsten label. The album’s title would prove prophetic: its corroded dance percussion, slashing post-punk guitars, and especially its creators’ zip code earned Liars a place in the new dancepunk canon, alongside groups like Out Hud, Radio 4, and the Rapture. This was the first and last time that it was possible to easily situate Liars in any one musical or cultural narrative, but even during this inchoate phase, there were signs that they were uncomfortable with genre constraints: the convulsive mechanical drum fills on “Mr. You’re on Fire Mr.” and the staticky musique concrète opening of “Garden Was Crowded and Outside.” They seemed as beholden to Suicide as to Gang of Four.

Liars arrived in New York City around the turn of the millennium, when “Brooklyn” was practically a genre unto itself. At this time, the band consisted of Andrew, Hemphill, bassist Pat Noecker and drummer Ron Albertson. In 2001, they released their debut, They Threw Us All in a Trench and Stuck a Monument on Top, on the Gern Blandsten label. The album’s title would prove prophetic: its corroded dance percussion, slashing post-punk guitars, and especially its creators’ zip code earned Liars a place in the new dancepunk canon, alongside groups like Out Hud, Radio 4, and the Rapture. This was the first and last time that it was possible to easily situate Liars in any one musical or cultural narrative, but even during this inchoate phase, there were signs that they were uncomfortable with genre constraints: the convulsive mechanical drum fills on “Mr. You’re on Fire Mr.” and the staticky musique concrète opening of “Garden Was Crowded and Outside.” They seemed as beholden to Suicide as to Gang of Four.

According to Andrew, Liars were surprised to find themselves pigeonholed, but even more surprised that people were paying attention to their music at all. He describes early Liars as a band without much of a point, more concerned with writing hot riffs. “We got to open a show for Sonic Youth,” he recalls, “and I remember feeling like we didn’t even deserve to share a stage with them.” For Andrew, music isn’t limited to sound: the visual, performative, and conceptual apparatus is as important as the recorded artifact, and he says that he even counts the discourse around a record as an important part of his overall process. As such, Liars committed themselves to staking out a territory that was more completely their own.

Liars’ next album, They Were Wrong So We Drowned, didn’t make a sudden left turn, it burned the map and burrowed into the earth. In retrospect, it makes perfect sense for a band determined to flout categorization, but at the time of its release by Mute Records in 2004, the album was utterly confounding to listeners who’d come to expect a certain level of accessibility from their dancepunk. Now, Liars’ debut resembles a sort of musical Trojan horse, where they secreted the paroxysmal bits that would soon become their primary medium amid a dancepunk framework. The slippages in their sound came to the fore on Drowned: it is a momentously difficult album, thick as molasses, impenetrably dim and forbidding. It found Andrew’s incantatory vocals pickled in a brine of murky drones, dilapidated percussion, acid-bathed guitars and bastard electronics. The record moved like something dragging itself through mud, forearm over forearm, and was danceable only in the most abstract, debased sense.

But a resistance to pigeonholing wasn’t the only motivation for Drowned’s sudden leap of faith: Liars’ personnel and practice changed significantly before it was recorded. Noecker and Albertson left the band to be replaced by Gross, cementing the streamlined trio that is the band’s most lasting incarnation. Where Monument took a couple days to record, Drowned took a couple months: Liars holed themselves up in a New Jersey cabin with TV on the Radio’s David Andrew Sitek to create the album’s adventurous sonics and abstruse witchcraft narrative. Andrew says that after establishing a foundation on their debut, Liars felt confident enough to venture further out, and inasmuch as the band’s transformation was a reaction to the culture of which they were an accidental part, it also stemmed from availing themselves of new tools. Armed with a sampler and a core membership likeminded in their commitment to unbounded exploration, Liars reinvented their approach to making music. “I realized that instead of playing a bass line,” Andrew recalls, “you could record a truck going down the highway, and that could become a bass line.”

But a resistance to pigeonholing wasn’t the only motivation for Drowned’s sudden leap of faith: Liars’ personnel and practice changed significantly before it was recorded. Noecker and Albertson left the band to be replaced by Gross, cementing the streamlined trio that is the band’s most lasting incarnation. Where Monument took a couple days to record, Drowned took a couple months: Liars holed themselves up in a New Jersey cabin with TV on the Radio’s David Andrew Sitek to create the album’s adventurous sonics and abstruse witchcraft narrative. Andrew says that after establishing a foundation on their debut, Liars felt confident enough to venture further out, and inasmuch as the band’s transformation was a reaction to the culture of which they were an accidental part, it also stemmed from availing themselves of new tools. Armed with a sampler and a core membership likeminded in their commitment to unbounded exploration, Liars reinvented their approach to making music. “I realized that instead of playing a bass line,” Andrew recalls, “you could record a truck going down the highway, and that could become a bass line.”

Drowned remains Liars’ most polarizing album to date: some fans and critics shunned the band for it, but for those of us who hung on, there was an exciting sense that this band was heading somewhere, pushing against some sort of boundary, and we were excited to follow wherever they would lead. Andrew confirms FANZINE’s suspicion that when Drowned drew mixed responses, some of them quite hostile, Liars weren’t discouraged, but instead felt as if they were on to something. “We felt as if we’d done what we set out to do,” he says. “That album probably got more write-ups than any of the others, even though it’s probably the least popular.” There was a sense that whatever Liars did next, it wouldn’t be motivated by a desire for perfection. Instead, it would be guided by intuition and a thirst for discovery: something altogether anomalous in a commercial climate that favored serial development over seismic upheaval.

Liars followed through on this tacit promise with their third record (for my money, their masterpiece), Drum’s Not Dead, released by Mute in 2006. If Drowned was compelling in large part because it felt like the work of a band at war with themselves, pushing the limits of their capabilities and often tripping over their own feet, Drum found them hitting the sweet spot. It sounded mystical and effortless, and while it retained Drowned’s droning aspects, they were alchemically transformed: everything that had been brown and sludgy became light and air. This new, ethereal Liars condensed the ritualistic freak-outs of Drowned around throbbing electro-acoustic percussion and Andrew’s haunting falsetto, and where Drowned lurched like a zombie, Drum glided like a apparition. It has a hallucinatory, perpetually startled quality, due in no small measure to the band’s move to Berlin, where they recorded the album in a broadcast center containing many rooms with many different acoustical qualities, which the band exploited to create the album’s mutating but always cavernous ambiance. In New York’s community of bands, Liars were a “thing.” In Berlin, nobody knew them, and Andrew remembers feeling galvanized by the new places and people. Viewed through this lens, it’s easy to interpret Drum as a documentation of the sense of wonder a new, strange location inspires. Andrew still resides in Berlin, returning to the States to write, record and perform with his bandmates.

Which brings us up to Liars self-titled fourth album, released by Mute in 2007. Liars, as I said before, finds the band more or less where they started, filling out relatively traditional song forms with their unique blend of industrial noise, tribal rhythm and rock instrumentation. This isn’t to say that Liars is a carbon copy of Trench. The latter drew heavily from classic British post-punk to inform its art-school brutalism; the former is rangier in its influences: putrefied dub, sparkly shoegaze, Liars’ weird version of blue-eyed soul, and the terse Krautrock rhythms that were so prominent on Drum are all folded into its bruising rock. It’s a thrilling record, but for a Liars fan who’d kept a close eye on their projected arc, it was also a tad disappointing: it felt as if the band were pulling back. But the more I sit with the record, the more I understand that, after probing the wild spaces of Drowned and Drum, a return to pop-oriented songcraft was the most expectation-defying thing Liars could’ve done. It’s a curve ball that at first seems a straight pitch.

Which brings us up to Liars self-titled fourth album, released by Mute in 2007. Liars, as I said before, finds the band more or less where they started, filling out relatively traditional song forms with their unique blend of industrial noise, tribal rhythm and rock instrumentation. This isn’t to say that Liars is a carbon copy of Trench. The latter drew heavily from classic British post-punk to inform its art-school brutalism; the former is rangier in its influences: putrefied dub, sparkly shoegaze, Liars’ weird version of blue-eyed soul, and the terse Krautrock rhythms that were so prominent on Drum are all folded into its bruising rock. It’s a thrilling record, but for a Liars fan who’d kept a close eye on their projected arc, it was also a tad disappointing: it felt as if the band were pulling back. But the more I sit with the record, the more I understand that, after probing the wild spaces of Drowned and Drum, a return to pop-oriented songcraft was the most expectation-defying thing Liars could’ve done. It’s a curve ball that at first seems a straight pitch.

To Andrew, Liars is an experimental record: after all the exploring his group had done, playing riffs and songs felt like “the next revolution.” While the album has no explicit concept, in the attempt to write “energetic, straightforward songs” the group found themselves revisiting their teenaged tastes, “that time in life when you don’t have a job or bills but everything feels so important, immediate and urgent,” from the corporate pop on which most of us were weaned to the first non-mainstream music we discovered on our own, building our tastes along with our identities. Liars documents a forward-looking group taking a look back, a cerebral group waxing visceral. What sounds at first like a regression, in context, becomes a full-circle, moving in one direction only: along the ley line of the band’s intuitive desire. Had Liars answered Drum with another ethereal oddity, they might have squandered the element of surprise to vital to their music. Only with a more traditional album could they retain their aura of suspense, and after Liars’ ostensible ground-clearing, there’s still no telling where they’ll go next.

For more on Liars see their official website. Or their Myspace site.

Credits on last photo and thumbnail: Title: 2007 photo shoot/ Artist: Liars/ Photographer: Joe Dilworth/ Date: 08 June 2007/ Usage Rights: press and promotions only/ Copyright: Joe Dilworth