Review: Patrick Wensink’s Broken Piano For President

04.05.12

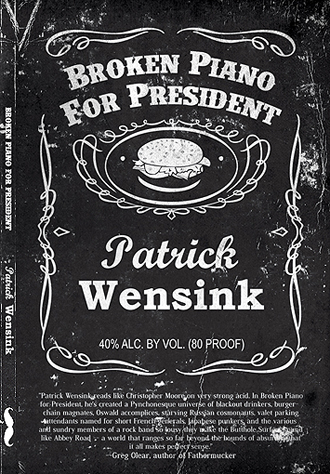

Broken Piano for President

Broken Piano for President

by Patrick Wensink

March 1st 2012

Lazy Fascist Press

Paperback, 372 pages

––––––

I received a package from Patrick Wensink last week. It arrived to my office via media mail, padded and wrapped heavily in packaging tape. Inside the envelope was a copy of his new novel, Broken Piano for President, a personal note from Patrick written with what appeared to be magic marker in a child-like cursive script (“child-like” in this case referring to its excellent adherence to the fundamentals), and a cassette tape. It was the cassette tape that obviously intrigued me most—since I was already three-quarters of the way through the digital version of his book (by the way, I’ve never read an ebook before and found reading a book in its PDF form not very much fun). What was even more interesting was that Patrick knew before sending me the tape, which turned out to be an audio book on side A—apparently read by Wensink himself—and 8 tracks by a band called Total Neutral on side B, that I still had a cassette deck. There it is, the JVC TD-W205 dual cassette deck given to me by an old roommate. I also noticed while writing this that I haven’t owned a CD player in almost eight years. I put the tape in and hit play.

The tape starts out tranquil and quiet, dare I say, bucolic, like the theme song to Fishing With John (with John Lurie), before meandering off in dark, brooding vibraphone patterns with occasional guest appearances by Brian Chippendale, the frenetic drummer from Lightning Bolt, and some female vocals drifting in and out of the atmosphere. The novel, on the other hand, starts out with a hangover, a screwdriver, and a bloody, matted mess of hair. Our protagonist, one Deshler Dean, we find, is used to mornings such as these. In fact, Wensink treats us, on occasion, to short lists such as these: “Deshler Dean’s Hangover Hall of Fame” which includes waking up in a pile of ingredients at a Dunkin Donuts and regaining sentience in the middle of a presentation in a marketing class. Dean is also the singer in an experimental art-core noise band backed by his roommate who moonlights as an assassin and a meth-head on drums. (Not unsurprisingly, the guest appearance of Chippendale on the Total Neutral accompaniment might have been an influence to the fictional drummer, known as Juan Pandemic, though not as the bone-thin character with picked-over skin who lives in a shack with a bunch of feral cats.) Unwittingly, or in Dean’s case, unknowingly, each of the these three friends are involved and intertwined in a much bigger plot—a seemingly never-ending battle of deep-fried deliciousness, skyrocketing calories, heart attacks, and chronic and cosmic one-upsmanship known as the Burger Wars.

The Burger Wars are waged between arch-enemies Winters Old-Tyme Burgers and their next door neighbor, Bust-A-Gut Burger, a revolving door of intermingling characters, and an endless supply of burger products ranging from the Fried Monte Cristo, the Winters’ Reuben Sandwich Burger, the Teriyaki Jerky Burger, the Bonzo Breakfast Burger (“three alternating layers of beef, cheese, fried egg and country sausage stacked Dagwood-style between two waffles.”), the flu Burger, and the revolutionary Space Burger, which apparently tastes like a crunchy, crispy, freeze-dried burger version of space ice cream. Lives will be lost in this Cold War nuclear stockpiling of sorts, and many condiments will be spilled. Our hero in all of this is, of course, Deshler Dean, only the space he occupies is that of an Alcoholic Werewolf: the many contributions he makes to the Burger Wars are lost to him in a state of blackout drunken-ness. “Friends call Dean the Cliff Drinker. Meaning when our hero goes out and has more than two, he falls off a boozy edge and forgets everything.” When he’s in this state of Cliff Drinking, Dean is the innovator of many of these products. He’s a double agent and a freelancer, playing both Winters Old-Tyme Burgers and Bust-A-Gut against each other in a drunken world of espionage and sabotage, none of which he remembers in the morning. From there, it unravels for him.

Dean sings for a band called Lothario Speedwagon. He cites in Chapter 16 his four most influential singers, each with their own caveat: Iggy Pop, David Yow, Nick Cave, and Gibby Haynes, whom Dean frequently conjures in his decision-making process. It’s Wensink’s inclusion of the number three, Nick “But only when he was in the Birthday Party” Cave because Wensink’s work is often referred to as absurdist humor. It’s striking to me because Broken Piano often reminds me in ways of Cave’s last novel, The Death of Bunny Munroe, in which our hero is a cocksman of the highest order who begins to lose his touch in the trade. When he’s unable to control that aspect of his life, and the more he tries, he is haunted by living nightmares, women he’s seduced run from him screaming, and he grows desperate. In a similar way, Wensink’s hero’s life is governed by forces he cannot fully explain or control—in this case Dean’s alter-drunken ego creates deals and expectations beyond what his sober self can possess. Everyone around him sees Dean as one in the same, except for Dean himself. As he struggles to put together the pieces of his shattered memories, bullshitting his way through business lunches while on break from his job as a valet, he’s also confronted with the responsibilities of a job he’s apparently really good at, but can’t reason how or why, and creating art that most everyone agrees is pretty terrible, except for some inexplicable reason, punk zinesters in Japan. Then again, the Japanese are into really weird shit. The more Dean attempts control, like staying sober for instance, the more everything crashes around him. His multiple bosses demand more innovation. His bandmates abandon him. His relationships go in the shitter, only to rebound with more drunken ideas, but he’s never quite sure why.

Wensink’s second novel has earned praises of being “Pynchon-esque” (I know I read that somewhere… oh yeah it’s on the cover), and I must say it’s true in creating a landscape of such ludicrous proportions. I think the best praise I can give it, aside from conceding its similarities to Cave and some of Pynchon’s works, is that twice during reading Broken Piano did I have to get up and urgently get a burger down the street.