The Mime Deals in Negation: A Review of A Twenty Minute Silence Followed by Applause

26.04.18

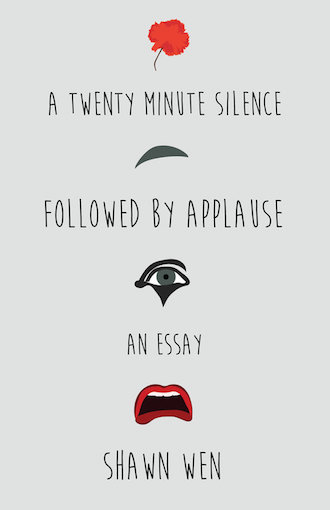

A Twenty Minute Silence Followed by Applause

A Twenty Minute Silence Followed by Applause

by Shawn Wen

Sarabande Books

$15.95 / 136 pp.

O there are deaths like witches of Arc

Scary deaths like Boris Karloff

No-feeling deaths like birth-death

sadless deaths like old pain Bowery

Abandoned deaths like Capital Punishment

stately deaths like senators

And unthinkable deaths like Harpo Marx

– Gregory Corso, “Bomb”

A Twenty Minute Silence Followed by Applause, the biography in blank verse of Marcel Marceau the famed French mime establishes critic Shawn Wen as strong new voice in literature.

Wen draws on various documents, to piece together the story of Marcel Marceau the silent performance artist, international sensation, and innovator. It’s a remarkable story, especially given the glory of Marceau’s mid-century career in performance.

It’s fascinating to look back at Marceau’s meteoric rise framed against the backdrop of 20th century conflict. Born Mangel, Marceau’s father was murdered in Auschwitz. “His brother emerged as a leader of the Underground in Limoges. Marcel became a forger. With red crayons and black ink, he shaved years off the lives of French children, too young to be sent to concentration camps.” This began Marceau’s inevitable flight and transformation. Marceau joined Charle’s Dullin’s School of Dramatic Art in Paris after the end of WW2. There he learned to focus on the body as the site of expression. “Leave speech behind. The body has it’s own language: weight, resistance, hesitation, surprise.” Marceau became a mime, and Bip was born.

The story is classical. And Wen operates within a generous imagination. There are some biographical details, but these are not really emphasized. As a documentarian, Wen captures ephemera. She describes Marceau’s different performances and scenarios. Bip is in a restaurant. He is at a party. He is wooing invisibles ladies. She talks about Marceau’s techniques, and describes his aesthetics of drama. She lists his books. She catalogs possessions: fetish masks, a Japanese fencer’s costume. It’s a lovely book. Quiet and quick. For me, evoking some of the wit of certain Echenoz titles (Lightning, Ravel) and just like in those books, Twenty Minute Silence mostly avoids biography. We get the enigma of Marceau the performer over the mundane details of Marceau the living person. Although Wen describes his pattern of womanizing alongside his remarkable longevity.

The aesthetics of Marceau come in the idea that silence is generous. By the 1960s, John Cage established a coherent vocabulary of performance based in silence. Before that, the cinema was a natural home for silent clowning: Harpo, Chaplin, Tati, Keaton, Lloyd. Jean Renoir’s dazzling achievement, The Golden Coach, captures the wild and kinetic spirit of commedia dell’arte, alongside the necessary laughter and raucousness of the performance, because clowns thrive on noisy crowds. Marceau’s silence evokes intentionality, drawing on the traditions of symphony halls. This is the silence of drawing room charades.

Middlebrow camp cuts through the ages. Douglas Sirk definitely occupies this space, as does the partnership of Emeric Powell and Michael Pressburger, and Mr. Arkadin era Orson Welles. Marceau also enjoys strange revisionist vibrations. Someone like Gene Kelly enjoys a less complicated legacy. He is generally celebrated as a performer. Marceau, however unusual, was formally simplistic and therefore similar to this kind of straight ahead performer. But he seemed especially interested in all of this “art talk” in the manner of the Orson Welles paradox, “It’s pretty but is it art?”

Wen describes a version of Marceau as an irresistible force. He is often introduced in terms of his physicality, emphasizing the truth of masculine beauty. It’s instructive to place this treatment into a historical context alongside works on Merce Cunningham, Bob Fosse, Isadora Duncan, Balanchine, and others, all arriving at the general conceit that the body doesn’t lie. Even famed gadfly journalist Mike Royko, the most straight-talking of any straight-talker, used to slide into a certain register when describing the athleticism of Gene Kelly. It’s a testament to Wen’s writing that the book is so entertaining. By relying heavily on ekphrasis and the enigmatic, she cultivates a sense of mystery. Readers become researchers engaging the legacy of a great performance artist.

It’s certain that middlebrow culture ages in interesting ways. Things once corny become more interesting in time. And so Marceau emerges as a camp virtuoso. Not nearly as funny as Charlie Chaplin, Harpo Marx, or Buster Keaton, he was something else. The mime Marcel Marceau was hardly considered high art during the height of his popularity. He was beautiful, but his was a camp beauty. And now there’s an almost illicit pleasure in revisiting his legacy. It’s a carnal bathos wash. It’s difficult to answer questions about innovation and form as it relates to mime. There’s an obvious tradition. And Marceau is explicit in identifying his influences. But it’s less clear why it matters. In A Twenty Minute Silence, the hook is so compelling, that it distracts from the obvious paradox that Marcel Marceau is boring.

But it’s obvious that Wen has uncovered an enormously pleasurable paradox. She describes a man living a blessed life. And a very long life. The strangeness of Marceau arrives in a sense of talking too much, oversharing the poesis in an attempt to clarify that this is of course a valid endeavor, and thereby, sort of ruining the punch lines. Studs Terkel apparently said, “Only one guy outtalked me. Marcel Marceau. I couldn’t get a word in.”

A mime is a terrible thing to waste.

Born in 1923, Marceau persisted as Bip until his death in 2007. There is something sublime in the death of a mime. A silent death. The mime is benevolent, a creative force. But by bringing visions into reality, the mime deals in negation.

Marceau lived thirty years after he decided he was too tired and bored to finish his memoir. He didn’t have enough time.

Wen identifies the way critics weighed in on Marceau’s long life. One commentator in The London Evening Standard, wrote “For me two hours of Marceau is like being trapped in a bar with an accomplished raconteur who insists on telling endless shaggy-dog stories.”

There was another titan of middle brow aesthetics, Joseph Losey, that caught onto the bizarre pleasure of mime death already in the early 1960s. In his sagging mod masterpiece, Modesty Blaise, Losey kills off a Marcel Marceau impersonator less than five minutes into the action. Mime death, silent, negating the negative, leaves only the memory of the performer, and the possibility of imagination to come.

Shawn Wen’s work is thorough and poetic. It’s a careful treatment of an enduring paradox.