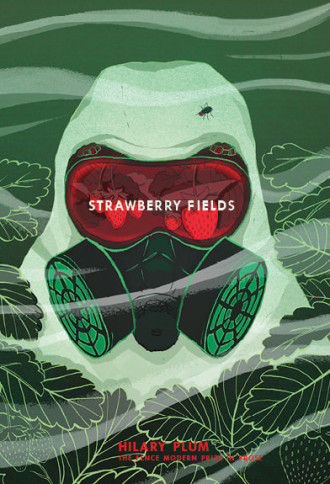

Alice: An Excerpt From Hilary Plum’s Strawberry Fields

24.04.18

In this excerpt from the novel Strawberry Fields, Alice, a reporter, is working on the case of five murdered veterans of the Iraq War. The investigation has extended in many directions, including toward the private military contractor Xenith. Here Alice recalls the early days of the war.

In this excerpt from the novel Strawberry Fields, Alice, a reporter, is working on the case of five murdered veterans of the Iraq War. The investigation has extended in many directions, including toward the private military contractor Xenith. Here Alice recalls the early days of the war.

Alice

Xenith landed in Baghdad in the heady days just after the invasion, didn’t miss a beat and in fact had beaten me there. I’d sat alone in an airport bar watching the shock and awe, firestorm in the night of an ancient city. It seemed that almost as soon as we freelancers had sorted our visas, stepped off the plane, charged our laptops, Baghdad had fallen. So there we were: birth pangs of an occupation. Coalescing around us what would be known forever after as the heavily fortified Green Zone.

I was there, I thought I was good to go. I’d found an interpreter but within a day lost him to the death of his mother. I could have tagged along here or there, made it work, but I caught some bug and spent day after day in my room sweating, thick-headed.

From my window I saw a war. A Marine unit doing sweeps, the same one always, I suspected, by my glimpses of a boy’s orange hair. Humvees and occasional tanks forced themselves down the street, fat cats squeezing through a pet door, I thought, feverish and tired of metaphors. I listened: sirens, traffic, distant explosions, it could have been a TV set to static. In the room next to mine a man shouted in an unknown language.

Once a day I forced myself out of the hotel and to a local teahouse, not the one where I was most welcome. I interviewed the regulars, but got little, no one wanted to talk to a flushed soft-eyed American, damp with some disease out of the heartland. I filled a notebook with sketched maps, brief interviews, impressions of the smells and prayer song, the migration of bursts of gunfire across the horizon. I photocopied a fourteen-year-old’s diary, loaned to me by its author. I think I believed that one day all this would signify something. Testify to something in the boundless history of war.

Walking too slowly back to my hotel one afternoon I ran into none other than my ginger Marine, hair just visible beneath his helmet. I nearly greeted him before remembering he wouldn’t know me. But he must have seen my expression on the verge of warmth, and from that day whenever he saw me he stopped me to chat. I couldn’t seem to avoid him.

The second time we met he pulled a handful of vitamin C packets out of a pocket and offered them, saying: I gotta say, you look like shit.

Thanks, I said, and wiped at the snot dried on my face.

More where that came from, he said: Embed with us and reap the rewards.

He looked pleased with himself. He looked not a day over twelve.

Goes against almost everything I believe in, I said.

I’m just talking good old-fashioned military-friendly journalism, he said, What’s not to love?

I’ll think about it, I said.

Don’t cry now, he said.

My eyes didn’t stop watering the whole time I was in that country. In my room I drank fizzing glasses of vitamin C, though I suspected it was far too late. Every day my interpreter called to say he’d be back tomorrow and for the first ten days I believed him. The truth was I didn’t care, or I cared too much. I stayed in bed. You all right? came the knocks at the door and a baby laughed on speakerphone through the wall. I thought, maybe this was the body’s natural response, or should be. To shut down, not go on with business as usual, if that’s what you could call foreign correspondence. I believed—no, something less than believed—that in my passivity I might claim a perspective no one else could, if I could exist in time so slowly, moment by moment as around me a nation fell to its knees, if I watched my ceiling and heard the long coda of an invasion, I would know something. Something else? Something more true? Looking back I can’t defend myself, can’t say what more true might mean, though at the time I wrote the phrase surprisingly often. I’d begin with the men, long dead, who had sat around a map and drawn the borders of what we know as Iraq. I would lead in with the history of colonialism, the fall of the US’s groomed leaders, the rise of the nationalists and theocrats. The gas attacks in the north we’d closed our eyes to, the weapons we’d sold. I would depict not just the scene before me but the motion of time within it, the forces of history that had pushed this nation to this wall, oil wells lit in the fields and not a flower thrown at our feet.

But I was silent, I was a woman, sick in a room. No country confessed its secrets to her. A people, a history, a language, a god, not one truth, though she waited attentive on street corners, notebook open for days. Every word I wrote anyone could have written. I filed some stories I don’t care to remember. Around me my colleagues and rivals assembled and I was slow to follow, looking off to the side, to the sky, to the ditches, the hands of children, begging or selling or waving a flag. Looking anywhere but at the page that was supposed to be mine. I walked the streets in a haze and if I turned toward anyone, I knew what they saw: a woman who did not share their fate.

You’re sick, the others said, when I tried to explain. Sweetly they left brandy at my door.

Alice! one day a voice cried behind me. I was leaning on a blast wall outside a half-empty market, watching the stalls get set up, rugs unroll. This was before the market bombings started.

How do you know my name? I asked Ginger, who was now beside me, pleased as any puppy.

He winked.

How’s the unembedded life? he said.

I love the taste of freedom, I said.

Come with me, he said. I have some real shit to show you.

Reader, what should I have said?