Privacy Given Freely: A Review of Shannon Burns’s Oosh Boosh

07.04.16

Oosh Boosh

Oosh Boosh

by Shannon Burns

421 Atlanta

$15 / 64 pp.

Before reading Shannon Burns’s debut poetry collection Oosh Boosh, I read a book by Tessa Laird called A Rainbow Reader. Part of Laird’s thesis as a doctoral candidate of Fine Arts, A Rainbow Reader is a book about color sectioned into six parts, with each part dedicated to a different hue. Red is indigenous, yellow sickly, blue simultaneously policed and iridescent. While Laird ties her research to theory and history, she’s as likely to reference works of fiction, weaving the segments of her reader together from a rich collage of sources. The final section, violet, is a mix of science fiction, death, and mythology—this is where we’d find Oosh Boosh.

This book oozes violet. “A Christmas Poem” asserts that before the baby god’s arrival on Earth, “there was only violet/ catalog light”. Violet is multiple; it envelops the senses, not only visual but olfactory: “It’s the violet fragrance as she nears it– / It’s the carpet. / The absolute silence. / The love of God.” The color is present even in its absence. There is a violet feeling exuding from poems like “Futuristic City”, which opens: “I’m looking everywhere for you/ in a futuristic city. I see you/ through a poisonous fog!” Later in the same poem, “My head is the futuristic moon but/ gentle, flaming balmily like a past/ moon.” This poisonous fog, these cosmic flames, could be any color, could be chartruse, red, or neon blue, but I see them in ultraviolet.

Colors bounce around in Oosh Boosh, untethered to violet. The short poem “Dog on Mown Lawn” confesses: “inside me my crumb/ of wretchedness glows/ yellow-red and goes out/ again”. Much like Laird in A Rainbow Reader, Burns seems often repulsed by the color blue, and as a result confesses in “Blue Thing Feeling”: “So I have touched blue things and blessed them and have said I am sorry to them, which is more than I have done for the red, orange and yellow things, the things I love truly, meaning love in the usual way.”

While Burns is not confined to violet, her thinking is mostly violet in nature. Her color-charged verse returns again and again to supernatural thoughts; there is a natural power to be gleaned from colors, but one that can only be accessed through special knowledge that Burns imparts to the reader: “One way to become spooky is to send love through your hands to a blue thing. One way to grow to like that blue thing feeling is to speak spells of kindness to blue things in shame for all your life.”

But Burns doesn’t only tell her reader how to be a witch, she is a kind of witch herself, using repetition to draw pictures on her reader’s mind. In “Love of Nude”, Burns asserts her own “young period of nude” and attraction to its associative colors. Nude becomes a chant, a spell—nude dress, nude desert, nude voice, the nude stone that “became a magic wand” to her, “The nude you heard then in my voice/ The nude I saw in others”. By the time we read “How nude unfurled its chill,” it is less “beige, pink, peach” than mauve, a light wash of violet.

Oosh Boosh tells a human story; it is caught up in the spectrum of human emotions—equal parts funny and sad. In its best moments, humor undercuts its creepiness, as in “Kinds of Handsomeness” where ‘Horrible handsomeness’ is “Handsomeness/ speaking the shiver-/ pitch of horror” but there is also the ‘house handsome’ contained “In a man’s kitchen,/ a handsome set/ of bowls.” The power of a witch’s memory is not lost in these abstractions, as “One may pull a detail/ of handsomeness to her/ through time/ and pinch it like/ hot glass to make a toy/ of it to wear/ upon her breast” like a talisman or voodoo doll.

Shannon Burns’s poetry can raise the dead. In the titular poem, “For My Dad (Oosh Boosh),” Burns is incredibly frank about death, opening with: “He was a big fan of mine/ and died”, and after a list of strange bodily confessions continuing with, “He saw all these things and thought more/ of me and died.” Burns’s sense of nostalgia and mourning is tied to a “cold sunny day”— an afterlife, perhaps—in which she asks her reader to “Help me give the wild dead a nice place to live in it,/ things to do, the feeling of being needed in it.”

Though feelings of loss, aloneness, and other-ness permeate this book, in the depths of its strangest feelings these poems are conversational in nature. Burns draws the reader to her by talking directly to them: “Oh look what the cat / has chosen” she invites in “Plumb”, and although the reader eventually feels a separation from the addressed ‘you’ as Burns continues, “Now / married we make a marigold / chain and arrange it / around the cat,” they are still drawn in, still invited to partake of this memory in a way they could not if they hadn’t felt addressed and included themselves. Burns’s world is private, but her privacy is being given freely. We the readers don’t know Kelly like Burns does in “Kelly Brutal,” but Burns describes her so delicately, dismisses her so deftly, recalls her in such incremental detail that we can’t help agreeing: it’s brutal.

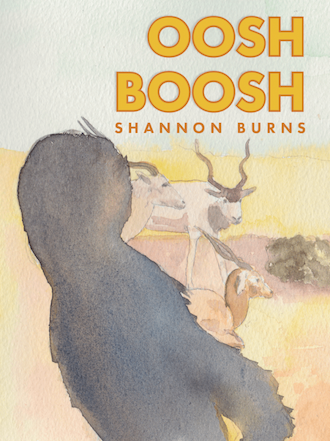

While the cover of Oosh Boosh is wondrous, to judge its interior by the horned beasts water-colored on its exterior would probably not yield a fair assessment. Instead, it is revealed in the lavender detail between their legs—or better still, the looming shadow in the foreground the reader’s eye dismisses at first glance. How does this unidentifiably humanoid shape go unnoticed? Once it is seen it cannot be unseen. It carries the antelopes on its back, hiding their hindquarters from our view. What is this shadow man? Could this swirling, dark plasma be the Oosh Boosh itself?