Paul Chan: Sade for Sade’s Sake at Greene Naftali Gallery, NYC

10.12.09

Paul Chan has become a kind of poster child of the politicized art world––and with good reason. In the late 90s Chan organized with the group Voices in the Wilderness to end sanctions against Iraq. Before the Iraq War, Chan traveled to Iraq where he interacted with Iraqi folk and made videos intended for educational purposes.

Paul Chan has become a kind of poster child of the politicized art world––and with good reason. In the late 90s Chan organized with the group Voices in the Wilderness to end sanctions against Iraq. Before the Iraq War, Chan traveled to Iraq where he interacted with Iraqi folk and made videos intended for educational purposes.

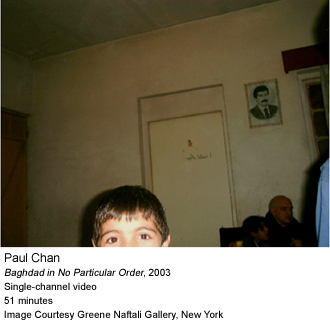

The results of Chan’s trip to Iraq are three videos which chronicle the before, during, and after of the Iraq War. The first video, RE: The Operation (2002), imagines Bush administration officials writing home from Afghanistan during the American operation post-9/11. As such, it is a witty satire of the Bush administration’s conduct following 9/11. The second video, Baghdad In No Particular Order (2003), consists of more or less raw footage of Chan interacting with people in Iraq before Iraq was invaded by the United States in 2003.

Riffing on the experimental ethnography of Jean Rouch, Chris Marker, Agnes Varda, Trinh T. Minh-Ha and others of the Cinéma Vérité film tradition, the video shows scenes from ordinary life. Twin girls dance to American pop music in their family home; a monkey sleeps in a hotel lobby; a boy dances enthusiastically (as if in trance) during the religious ceremonies of a Mosque. In the third video, Now Promise Now Threat (2005), Chan returns to his native Nebraska where he gathers footage, once again, of the folk. What this video reveals is the contradiction of people’s cultural attitudes, which are less connected with a national political discourse than ultra-local religious ones. Now Promise Now Threat, Chan claims, led him to think more about theological questions as they connect art and politics.

Something that has impressed me about Chan’s work since first encountering it in the early aughts is its negotiation of activism and problems specific to art as a field of knowledge. Like the early modernist motto "art for art’s sake," Chan has famously (and controversially) taken a position that partitions his work as an activist from his work as an artist. What the art aims for instead of a politic effect is "freedom," and a sense of "contradiction"––that the elements of artworks are unresolved, and therefore resist ideological coherence or comprehensibility.

Something that has impressed me about Chan’s work since first encountering it in the early aughts is its negotiation of activism and problems specific to art as a field of knowledge. Like the early modernist motto "art for art’s sake," Chan has famously (and controversially) taken a position that partitions his work as an activist from his work as an artist. What the art aims for instead of a politic effect is "freedom," and a sense of "contradiction"––that the elements of artworks are unresolved, and therefore resist ideological coherence or comprehensibility.

Despite this position, Chan’s recent work has been extremely socially and politically engaged. In Chan’s 2007 production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot in the 9th Ward of post-Katrina New Orleans, the artist worked with locals to organize the production. Surely, one can perceive this aspect of the production––the pre-production community meetings, advertising, and rehearsals––as stemming from Chan’s activism, and specifically his work with Iraquis via Voices in the Wilderness. By addressing the needs of the 9th Ward’s inhabitants––what they might want from a work of art? how a work of art may serve them?–– Chan would seem to provide the perfect negotiation of activism and aesthetic production. The activism and artwork, moreover, would seem to involve a single investigation of the ways practice and theory enfold and inflect one another through a set of consequences (what either activist or art work may yield as effective).

The immediate consequences of Waiting for Godot one can read about and view at Creative Time’s website (Creative commissioned the piece). People came together to see Beckett’s canonical play performed in the 9th Ward complete with free gumbo, a Mardi Gras-style procession, and using "props" and "stages" left-over from Katrina. Whether the production helped the people to overcome their own sense of “waiting” (deferment or abandonment) is a question I would like to ask Chan himself, since the success of the work—based on Chan’s articulations of the work’s intention—would seem to hinge on whether it brought relief to the 9th Ward’s plight.

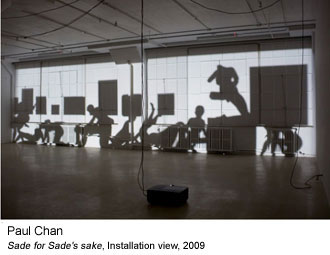

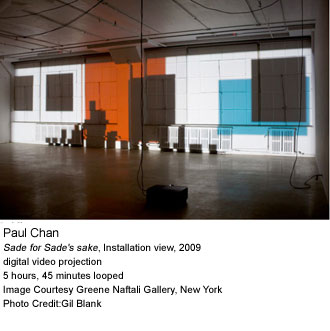

That Chan can keep one foot in activism at this point seems a feat, given his commercial success as an artist. I could not help but think of this success as I took in his show at Greene Naftali gallery, Sade For Sade’s Sake, which features a nearly six hour wide-screen video taking its inspiration from the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom, Sade for Sade’s Sake (2009), large-scale drawings using "fonts" developed by Chan, and a host of erotic/pornographic drawings after Matisse and other modern and contemporary artists.

That Chan can keep one foot in activism at this point seems a feat, given his commercial success as an artist. I could not help but think of this success as I took in his show at Greene Naftali gallery, Sade For Sade’s Sake, which features a nearly six hour wide-screen video taking its inspiration from the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom, Sade for Sade’s Sake (2009), large-scale drawings using "fonts" developed by Chan, and a host of erotic/pornographic drawings after Matisse and other modern and contemporary artists.

Chan’s video is clearly a return to two of his early animation videos. The first animation video, Happiness (Finally) After 35,000 Years of Civilization (1999-2003), featuring animated images after the drawings of Henry Darger connects to Sade for Sade’s Sake not only by its animation style, but also by its themes: war and pornography. In Happiness (Finally) After 35,000 Years of Civilization, Chan links pornography and war together through Darger’s epic drawings of naked, androgynous children battling with a belligerent adult population. Darger’s world is simultaneously a utopia (a non-existent place one might wish to live in) and a distopia (a place fallen from such wishes) in that the children represent a paradise encroached upon by adult miseries (war, sexual discrimination, destruction of a natural landscape).

The animation style of Sade for Sade’s Sake resembles Chan’s earlier video work, The 7 Lights (2005-2008), a work deriving from 9/11 imagery, but playing on ancient themes from world religion (apocalypse, creation, mourning after natural and social disaster, etc.). Seeing Sade for Sade’s Sake one recalls the freefall silhouettes of The 7 Lights. Likewise, squares representing objects, picture frames, and windows are key to both works––windows most of all.

Why the squares/windows? Chan’s playing on scale and abstraction through use of geometric shapes seems to derive from Kasimir Malevich’s Suprematist paintings. At one moment the squares are windows along the facade of a fortress (perhaps the prison that held the Marquis de Sade?); at another they are falling off the walls (picture frames cartoonishly coming unhinged). The squares also represent objects in the foreground and background (space is flattened by Chan’s iconoclastic use of these black and colored squares on a white background). Finally, these squares represent objects carried by the slaves who appear in the video silhouetted, entering and exiting the left and right sides of the video projection as though upon a stage.

Why the squares/windows? Chan’s playing on scale and abstraction through use of geometric shapes seems to derive from Kasimir Malevich’s Suprematist paintings. At one moment the squares are windows along the facade of a fortress (perhaps the prison that held the Marquis de Sade?); at another they are falling off the walls (picture frames cartoonishly coming unhinged). The squares also represent objects in the foreground and background (space is flattened by Chan’s iconoclastic use of these black and colored squares on a white background). Finally, these squares represent objects carried by the slaves who appear in the video silhouetted, entering and exiting the left and right sides of the video projection as though upon a stage.

Seeing Chan’s recent work, I am also reminded of Kara Walker’s signature silhouettes. When one sees Walker’s drawings, paintings, and animation, one immediately recognizes Walker’s referent––antebellum Southern slaves and their white masters. These images are both negatively stereotypical and historical. As such, they compel their viewer to feel outrage, empathy, and to come to terms with one’s own complicity with legacies of slavery (when I saw the Walker retro at The Whitney in 2007, I was in fact struck by the reverence of the crowd; the sheer quantity of Walker’s reiterative works gathered together had an overwhelming force). Chan’s figures, derived from Sade’s masterpiece The 120 Days of Sodom, have no obvious historical referent other than Sade’s book. They are mythic and archetypal depicting the generalized slave of Sade’s work, the slave as Sadeian concept. Unlike Walker’s figures, Chan’s own would seem to have neither racial or class feature. There are men and women slaves, though only men get to be masters. I am admittedly suspicious of this de-historicizing (if not de-politicizing) effect of Chan’s video.

Throughout the video we see the slaves moving heavy objects across the screen. Since there is no depth of field to the figures or the objects they carry figures and objects tend to flatten one another. The projection has a slight blur to it. Whenever I encounter a blur in film, painting, or photography I immediately sense a deformation is occurring––something being returned from form to formlessness. Insofar as Sade himself intends to deform God as a referent for “natural” order and “normal” human sexual behavior, Chan’s blur seems appropriate.

Throughout the video the masters confer among themselves. Like their slaves, they are naked. Their large penises dangle and jut out. Slaves crawl across the stage of the video’s wide-projection, sometimes they crawl on their hands and knees. They also cluster together in sexual orgies. During this clustering the figures twitch. There is a general twitch throughout the video, which represents both an orgasmic shudder (a petite mal), and the threat of the grand mal under torture or social meltdown (infrequently the video will just seem to shut off, as though someone had yanked the plug on the video projectors).

Throughout the video the masters confer among themselves. Like their slaves, they are naked. Their large penises dangle and jut out. Slaves crawl across the stage of the video’s wide-projection, sometimes they crawl on their hands and knees. They also cluster together in sexual orgies. During this clustering the figures twitch. There is a general twitch throughout the video, which represents both an orgasmic shudder (a petite mal), and the threat of the grand mal under torture or social meltdown (infrequently the video will just seem to shut off, as though someone had yanked the plug on the video projectors).

The flickering that goes on in Chan’s video inflects Chan’s preoccupation with the negative, a negativity which can act inversely as an affirmation of what a viewer sees, and point to the fact that we are seeing at all. Flickering forms a metaphysical axis in Chan’s work, one that is hard to pin down but nevertheless present. Were I to write a more theoretically arduous article on Chan I might consider at length this flicker in terms of Theodor Adorno’s modernist aesthetic theories, which I suspect Chan has read quite closely. The way Chan talks in his many interviews strikes me as Adornian anyway, however he evokes the names of a host of different philosophers, essayists, and theorists.

Chan’s tarrying with the negative also comes across in a series of poems he wrote from 2005 through 2009, Texts, in which many of the words of the poem are crossed out. These "erasures" (the popular term for poetic texts produced by the crossing-out of words) form interesting language effects. Reading the poems for a first time, the words that are crossed-out stand out. Reading them a second time, I read them without the cross-outs. The meaning differs radically depending on whether you read the poem with or without the cross-outs; the first reading yielding a wildly aphoristic poetry, the lines of the poem wending and cutting-off like a poem by Emily Dickinson or Robert Creeley, the second reading yielding something more bare. In the second reading you get something radically reduced, yet equally pithy and contradictory—like a koan or revolutionary slogan from May ‘68. These poems I read beside much of my favorite lyrical poems being written today for the ways that they foreground dialectic tension, and negotiate a theoretical lingo with common speech.

Inhabiting Chan’s nearly six-hour video, there is something powerful about watching so much black against white/light. In Wallace Stevens’ poem, “Domination of Black,” Stevens represents the scene of a universe turning upon its speaker, crushing the speaker of the poem with its chaotic density. There is a similar effect in Chan’s video. One starts to feel overwhelmed at moments—like the universe is turning on you. All that black does dominate inasmuch as seeing the black (i.e. negative space) affects the senses. I felt profoundly tired after watching Chan’s video for a few hours. Perhaps Chan’s use of negative space over such a long duration contributed to my sense of weariness.

Inhabiting Chan’s nearly six-hour video, there is something powerful about watching so much black against white/light. In Wallace Stevens’ poem, “Domination of Black,” Stevens represents the scene of a universe turning upon its speaker, crushing the speaker of the poem with its chaotic density. There is a similar effect in Chan’s video. One starts to feel overwhelmed at moments—like the universe is turning on you. All that black does dominate inasmuch as seeing the black (i.e. negative space) affects the senses. I felt profoundly tired after watching Chan’s video for a few hours. Perhaps Chan’s use of negative space over such a long duration contributed to my sense of weariness.

The question I kept asking myself watching Chan’s video was: why Sade? The press release for the show states that for the past few years Chan has been making work exclusively after the Marquis. One reason (that has two names) seems obvious: Gitmo and Abu Ghraib. The Bush administration remains Chan’s central foil, and as such Chan will probably be remembered and studied as one of the most important American artists––if not the iconic American artist––of the Bush era. That the Bush administration broke with the Geneva accords, encouraging torture among its military and governmental agencies, is a source of guilt and shame that the United States has yet to properly resolve––neither through symbolic exchange or legal retribution. One can only hope an aesthetic practice like Chan’s signals the beginning of a process of desublimation that can properly deal with the United States’ ongoing crimes against humanity.

But we are also living in a time of virtuality, and the pornographic is one of the predominant mediums of the virtual. Throughout his writings and interviews, Chan makes reference to the primacy of Lacanian cultural theory for the past twenty years. This primacy does not seem a coincidence given the central idea behind Jacques Lacan’s theory of the subject: that the subject’s "reality" is a construction of what he or she "imagines," whether this takes the form of a belief structure, fantasy, or ideology. Pornography has always been an exemplary scene of imaginal encounter. And so I think Chan chose the Marquis de Sade as muse because Sade represents an age of both extreme cruelty and virtuality (the fact that what we imagine constructs what we believe rather than the reverse). In an age in which torture is permitted by one of the most civilized societies in the world, language cannot help but suffer, reduced to a vehicle and byproduct of injustice. In the early stages of any totalitarian society, language is the first victim. Chan points to this fact through his most recent show.

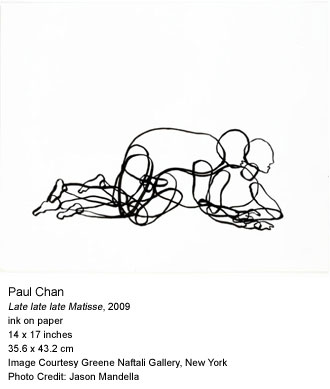

Lancanian cultural theory has often been charged with being overly discursive, prioritizing language over the bodily “real,” reducing the body to a set of language effects and a neo-Cartesian formula. Whereas the primacy of the animated image of Chan’s video produces a bodily effect (the black squares affecting their viewer over the course of six hours), Chan’s other works in his show perform something altogether different. These works consist of drawings deriving from Matisse, Mark Lombardi, and Cageian-Fluxus scores, and as such form a dialogue with their sources.

Lancanian cultural theory has often been charged with being overly discursive, prioritizing language over the bodily “real,” reducing the body to a set of language effects and a neo-Cartesian formula. Whereas the primacy of the animated image of Chan’s video produces a bodily effect (the black squares affecting their viewer over the course of six hours), Chan’s other works in his show perform something altogether different. These works consist of drawings deriving from Matisse, Mark Lombardi, and Cageian-Fluxus scores, and as such form a dialogue with their sources.

In the Cagian-Fluxus scores, Chan’s wish is to score pornographic language, as though to recall a language of repetition back to the body through performance—to thus exorcise or merely exercise this reduction of common language? Many of the scores appear blank (just bars of sheet music), and as such seem to await inscription, or perhaps interpretation (being played). This use of scoring is provocative to me as a way of evoking the body of the audience—their potential to sing or utter—as I believe many Fluxus and intermedia scores of the 60s and 70s also do.

In another drawing one sees the relations of characters from The 120 Days of Sodom drawn diagrammatically, not unlike Mark Lombardi’s drawings that chart geopolitical and economic flows of power. Such drawings playfully historicize the relations among Sade’s characters, showing there to be lines of force and hierarchy from which Sadist persecutions originate. Doing so, Chan recalls Sade back from the writer’s literary-philosophical predominance, inflecting Sadeian categories through a set of historical relationships.

In a set of drawings, drawings which could be after Matisse but also could be a reference to Bruce Nauman’s pornographic neon sculptures in which figures give each other head and point guns at one another and bodies holographically overlap in sexual poses. However, iconoclastically, once again Chan recalls pornography (the virtual) to the body, mediating pornographic perception through traditionally "high-art" drawing techniques. This mediation seems crucial for experiencing the body again, pornography being a kind of erasure or etherizing of the body in repetition.

Chan’s latest showing also consists of large-scale drawings of "fonts" invented by Chan. These drawings are in conjunction with a computer keyboard in which all of the keys have been replaced by gravestones and an actual computer in which one can play with the fonts and generate their own text. The fonts derive from pornographic phrases and words. I am not sure exactly how Chan generated the fonts, but it would seem that the fonts were conceived by a procedure (a computer program that equates key strokes with phrases and words). When one types the capital and lower case letters of the keyboard, as well as the numbers, comma, period, and questions mark keys, one generates sentences based on the language Chan has programmed.

Using this computer procedure, Chan has rewritten works by John Maynard Keynes, Gertrude Stein and others (and one can read these texts at Chan’s website, National Philistine. The large-scale drawings feature "decoder" legends showing keystrokes and their graphic counterparts. It is interesting that Chan has chosen to use drawings to explicate his fonts. Is this to sell a collectable art object (where the more dematerialized ones might have sufficed) or as yet another form of mediation? One suspects both.

At the base of the drawings’ frames are shoes. The shoes are from various walks of life. There are the shoes of the middle-class business man, of business casual (a hybrid sneaker shoe), and a grungy pair of Nike Airs (Chan’s use of shoes, like his use of objects in The 7 Lights is stereotypical, if not archetypal). Where once stood actual bodies, language stands in their place, a generalized pornography of stock words and phrases: “give it to me,” “suck it,” “more, oh more”… etc.

In recent interviews Chan has said that the primary investigation of his recent work is religious inasmuch as sacral matters interlock with those of economics, politics, and cultural struggle. His pursuit of this investigation is reluctant, however necessary. In an essay that appeared last month in the quarterly journal October issue #129, “The Spirit of Recession,” Chan addresses his sense of contemporary religion through the notion of “recession.” In this essay, Chan would like to play on the secular and religious notion of recession. In economics a recession refers to a time in which economic confidence has withdrawn. Yet in religious ceremony, the recession is the moment at the end of a religious service when worshippers return to their ordinary lives, thereby interrupting their period of worship. Recession, particularly in this later sense, is a time in which we can transform our lives, since they are no longer given to the subservience and docility of religious observation (an observation which Chan equates with deregulated global Capitalism).

I am not sure what to make of Chan’s turn to metaphysics, or the fact that his project has always been, at bottom, a metaphysical one even when it would seem to be serving a practical political use. I am wary of it, seeing all of the bad religions have done in the 20th century, and seeing a real need for art and poetry to exist outside religious discourse. Yet, I trust Chan’s intellect––there are few artists I know who are doing more to reflect on the stakes of their work for realms beyond art world problems and concerns. How to maintain a politics while investigating a metaphysics of culture and economics?–– Chan’s work burns with this question. How not to foreclose any of these realms of experience; how not to suture their separate truths—a fate that contemporary philosophy has warned us of in regards to social-political struggle (Alain Badiou, Jacques Ranciere)? Art, for Chan, is at the center of this negotiation. His use of Sade only extends this conflict further, risking a reduction of politics to metaphysics, and art to theology. Yet, it is history that has brought us to this critical juncture in art, and this is a fact I believe Chan to be all too aware of too.

–––––––

note and apologies: the captions were out of order for a bit. Fixed now! Also the complete info for image on page 1 is the following:

Paul Chan

Sade for Sade’s sake, Installation view, 2009

digital video projection

5 hours, 45 minutes looped

Image Courtesy Greene Naftali Gallery, New York

Photo Credit:Gil Blank