On Lynn Crawford’s Shankus & Kitto: A Saga

14.09.17

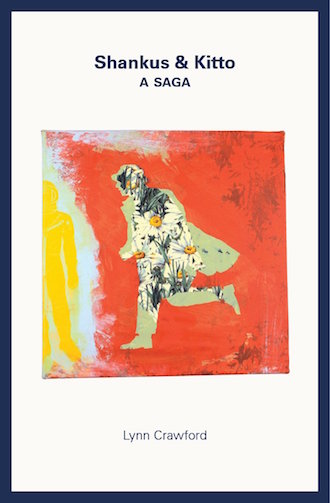

Shankus & Kitto: A Saga

Shankus & Kitto: A Saga

by Lynn Crawford

DittoDitto

141 pp. / $16

Lynn Crawford’s new novel is an inside-out family epic where, instead of the usual sweep of generational time, we are given a perspective that allows us to see familial heartbreaks as a telescoping and ever repeating fractal.

The first installment of a projected diptych, Shankus & Kitto: A Saga tells the story of a first generation Greek-American couple who run a restaurant serving traditional food. Their son opens an offshoot restaurant in gentrified “downtown” where, to attract the locals, he reluctantly adjusts his menu.

“George,” he confides to his brother, “this neighborhood is killing me.” He points out a table full of customers and continues, “Not a meat eater in the fucking group. For awhile I got some of them to go with me on the, High quality meats from animals that lived high quality lives, campaign, but they faced peer pressure, you know, they all do yoga. And some of their teachers tow a hard dietary line.”

Hilarious about the mission creep of New Age food choices as she is also on the infantilizing power of technology, Crawford is an accurate, sometimes mordant, more often earnest, observer of a new normal:

I walk down the street, check my phone regularly. Well, maybe a lot. But a lot compared to what? I just am not sure since I see people–not that I snoop, though it might sound like it– bend over phones in the library, on the subway, at the grocery store. Maybe they are reading poems or political articles, or looking up meal suggestions or ten minute work outs. BUT, but, maybe they, like me, are hoping for, banking on, a message from a certain someone.

A parallel but thankfully not equivalent arc to the redemption story, one of the central points of the book is to remark upon the generative power of suffering. Referencing a different saga, a character says that it is “unhappiness that ignites existence or, in any case, breeds stories.” The separated people of Crawford’s novel are in a repeating and very familiar condition, propelled by their unhappiness.

Dino, the restaurateur son, is having an affair with Ily, which devastates his wife, Meg, for whom Dino’s financier brother, George, carries a torch. How these characters and their intertwining stories are presented is part of an unexpected strategy that Crawford employs to demonstrate family’s discontinuous and yet oddly recycling narratives. Monologues are told from Cubist angles and unforeseen perspectives: Ily, we see mostly as a young adult away from home for the first time at culinary school in Europe; Meg is both recovered, and at the lowest point of devastation, from her husband’s affair; and Meg’s narrative is complicated by her mother’s fiction, which are embedded in Meg’s monologues and which oddly recount the immigrant tale of Meg’s in-laws.

This interweaving tableau is told in a singular yet disarmingly familiar style that mimics the rhythms of a Midwestern voice but without recourse to the relatively cheap tricks of regionalism or slang. At one point, speaking about a list of decidedly non-gourmet favorite foods—a list which included “aerosol cheese” and “red pop”—a character says, “Another reason I keep that … food list … is to remind myself it is ok to behave and eat like a dope. If you never allow yourself that you stop growing. Intelligence, sophisticated palettes, articulate sentences, all have their place but, in excess, function as armor… Allowing those moments to savor junk, sound ill- informed, is an experimental, risky, gesture; possibly one paving roads to growth, expansion.”

Crawford’s voices capture a particular type of everyday speech. William Carlos Williams, arguing for an American (immigrant) context said that his work derived from “the mouths of Polish mothers.” By writing in a poetry of vernacular, Lynn Crawford has similarly and bravely gone against the grain and in doing so has slyly re-constructed the family epic.