On Institutional Garbage

13.12.18

Does the digital envy the analog, the haptic sense of its excesses, the paper trail’s disarray? Is it nostalgic for the language and forms that filled the briefcases of bureaucracy? Does it envy the overflow of books and paper onto desks and floors and burgeoning from trash bins? This was not so many years back, that time when we would carry the physical detritus of our institutions with us, filling backpacks and briefcases and so many file drawers—the ways this impinged on our physical space.

Our excesses haven’t diminished, they’re only better hidden. We have cultivated a sense of digital manifest destiny, that feeling that somehow because we’re not at capacity we can accumulate information in seemingly limitless ways. But how can we even attempt to process what’s already there? The Wayback Machine at archive.org saves 300 million web pages each week because, as the site claims, “The Web needs a memory, the ability to look back.” But we also need new ways to see. My email inbox has 1,247 emails unopened and waiting and that alone seems not optimal though perhaps one day manageable until I factor in the “Everything Else,” which is currently at 14,277 and rising and this number makes me feel like I have a problem with discarding; I have had onlookers glance at this number on my phone and exclaim with concern for my lack of digital upkeep. Is it information fatigue? Do we all suffer from it? Signs include apathy, indifference, mental exhaustion.

Why do we cling to these traces? Is it the anxiety of our embodiment when so much of our lives transpire in a digital landscape? Our digital waste is nowhere and everywhere. It has less value because it does not have to justify the space it occupies.

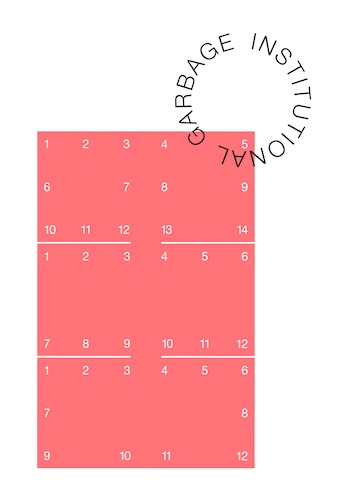

“The general principle that has emerged is excess. Always a lot and too much,” the publication manager reflects, on the catalog for the online exhibition. Its excesses perhaps all the more apparent in this physical aggregation, as archive of what previously existed as data—bytes and megabytes hovering in the cloud.

Paper excesses are more conspicuous. Consider, for example the Security and Exchange Commission circa 2003, their headquarters in Washington DC was imaged via satellite every few months to monitor the integrity of the office building, to assure it could continue to bear the weight of its own paperwork. Fifteen years later the weight of retaining information is no longer a concern, even if the volume has, if anything, increased. An insider tells me, “IT says we take in enough data that receiving hard copies would require multiple large trucks every day.”

“There is a desire to hold on to what is now gone or missing,” the editor comments, as if she must justify the physicality of the catalog for an exhibition that only existed online.

In Adrian Piper’s solo show at MoMA, one shelf held a series of jars filled with Piper’s hair and nail clippings, surely only a fraction of What Will Become of Me. For 38 years Piper has collected her hair and nail clippings for this work, which will be complete upon her death, once her remains are added. A document bequeathing the work to MoMA is also included—a bold move, perhaps then an absurdity in itself, but now a truth, a wish fulfillment executed too soon, as it has already become part of MoMA’s vast collection.

I was struck by the way the artist transformed all of her growth into art, even her nail clippings have become a form of production. This bequeathing of one’s physical traces opens so many questions. Is this collection a manifestation of Piper’s existential anxiety, of holding on to relics to mark time? Piper’s body is literally becoming part of the institution even in this moment. Her body is now an institutional body, and is always producing.

But also, I just looked at MoMA’s web site and at an image of this shelf holding twelve jars of hair and two of nails, and now it seems that must have been what I saw displayed in June.

But is it? The experiences have merged in my mind, and this makes me wonder what it means to gaze at this image of Adrian Piper’s hair and nails on my laptop screen, removed from their physicality.

And what does it mean to consider an online exhibition of physical objects now archived in a physical catalog while I am reading a PDF of the catalog in DropBox? These many degrees of removal from the works and the online exhibition don’t feel like distances at all but rather like I’m retracing their discontinuous existence while reimagining their varied articulations. The no-longer existing imaginary institution documented in Institutional Garbage has vanished but not entirely –nothing on the web ever disappears completely. I stumbled upon a backdoor cracked open and entered like a fugitive, and was soon overwhelmed by my attempt to note the variations between the catalog’s archive and the exhibition, that even in its nonexistence seems to be very much alive.

And what does it mean to consider an online exhibition of physical objects now archived in a physical catalog while I am reading a PDF of the catalog in DropBox? These many degrees of removal from the works and the online exhibition don’t feel like distances at all but rather like I’m retracing their discontinuous existence while reimagining their varied articulations. The no-longer existing imaginary institution documented in Institutional Garbage has vanished but not entirely –nothing on the web ever disappears completely. I stumbled upon a backdoor cracked open and entered like a fugitive, and was soon overwhelmed by my attempt to note the variations between the catalog’s archive and the exhibition, that even in its nonexistence seems to be very much alive.

Here inside, The Checkout Girl Manifesto has yet to be loaned out, and Webcamcurator’s series of video stills have come back to life. Rather than an anomaly this back-and-forth between analog and digital feels to me akin to what Brian Massumi refers to as the challenge “to think (and act and sense and perceive) the co-operation of the digital and the analog, in self-varying continuity.” It’s within these cracks and fissures that the virtual comes to life, and the institution too.

Consider the cracks between the surface and image of Daniel Bortzuzky’s Data Bodies, a chapbook that sits on my own shelf, and yet was an object in the online exhibition, and another configuration is included in the catalog. Data Bodies acknowledges the continuity of physicality and data; our selves have merged with the data we produce and we are all faxed and transmitted and flooded and stored.

Images show the chapbook physically spliced, exposed, disordered, and like many of the traces of the online exhibition, there’s a sense of movement, of presence, a necessity of negotiating space in new ways. I am talking of the digital version of the physical text but imagine what you’d like.

The editor almost apologizes for having had to ask patrons “to take their time and have a bit of patience – demands that seem anachronistic to the internet,” but this is a serendipitous invitation for visitors to participate in an act of wasting time. Or, think of it as another way to access the Art Labor Archive, where, as Jill Magi writes,“Time is deinstitutionalized and nonstandardized in this ritual even as the session occurs inside the institution and is monitored by the timer, the teacher.”

These moments of questionable productive value, could be called wasted. Though this is where one finds a backdoor in to the institution, and creates small fissures in the hegemony of productivity. It’s the place we discover we’re already entangled inextricably between these two realms. Like a digital version of the physical document of a digital exhibition.

Perhaps it’s best that I print out the PDF and set the manuscript beside hair collected from my sink, then photograph and upload and destroy, and on we live.