A Hunger for Truth and a Taste for Toppings: A Conversation with Eileen G’Sell

17.12.18

I met Eileen G’Sell on Craigslist. I was trying to sublet my room and escape New York City, while she was looking for a room so that she could escape St. Louis. She liked that my place was dog-friendly; I liked that she was Google-able as a real live person and therefore, (somehow) less likely to steal my shit or axe-murder my roommates. Cut to the end of the summer when I returned from my travels to find Eileen and her beloved dog, Holden, on my couch with a bottle of wine and the beginning of a now years-long friendship marked by riotous laughter and rigorous conversation about gender and pop culture, writing and publishing, love, sex, and social justice. This was the summer that Eileen began to step fully into her now successful career as an essayist, which has lead her to write extensively for Salon, Vice, Hyperallergic, and other well-known outlets, as well as spend two years on the editorial team at The Rumpus—first as the film and media editor, and then as a features editor. But Eileen’s first love has always been poetry.

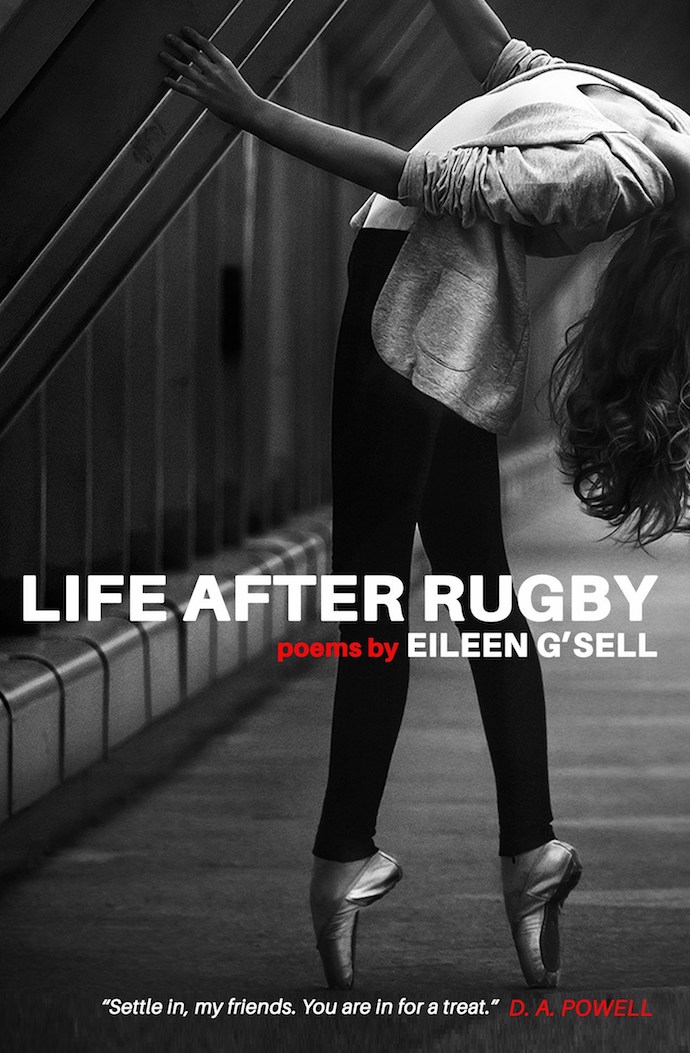

Earlier this year, her first full volume of poetry, Life After Rugby, was released from Gold Wake Press to critical acclaim from such poetry powerhouses as DA Powell and Shane McCrae, among others. The hallmarks of Eileen’s work, regardless of genre, are razor sharp intellect, strong political conviction, and a quality of playfulness which are all on display in her debut effort. In her poem, “The Reason the Moon Moves,” Eileen writes: My attentions / were coolly divided between a hunger / for truth and a taste for toppings. And in response my marginalia reads: This. So very Eileen!

Though Eileen still splits her time between St. Louis and NYC, this particular conversation between friends happened via phone and email.

11.7.2017–Eileen G’Sell, teaches rhetoric and poetry at Washington University in St. Louis..Photos by Joe Angeles/WUSTL Photos

LL: Because I got to know you as an essayist first and because I love a good origin story, can you tell us your poetry origin story?

EG: I probably first came to poetry as a songwriter. As a child I always gravitated towards writing and singing songs, often as a way to occupy my time and feel less lonely. I’m pretty extroverted as a grown up, but as a child I was really shy. I’m not actually sure if I was naturally shy, or if I was just ostracized so often that I thought things would work out much better if I didn’t openly express my personality. I began writing these songs in preschool and singing them to myself on the playground, in the car, in my house. It was like a secret I had where I knew in my mind I was a soon-to-be-discovered child pop star and no one else knew. This was the heyday of Star Search, so that was very influential to this delusion. I think the instinct to rely upon rhythm, certain aspects of rhyme, the sounds of words, and a way to express interiority—this all came through songwriting. Then, when I actually learned how to write, that was such an amazing experience. I just remember feeling like, Oh my gosh, I can make this permanent.

In Life After Rugby, you work with a range of content and form, the cohesion of the collection really coming through in its thematic elements. One of the most pervasive and compelling themes that I read across both your poetry and cultural criticism, is an interest in exploring power. What are the central questions regarding power that you’re grappling with in Life After Rugby?

I think that some of my questions have to do with how one comes into the world having a certain degree of agency and how it can be stripped away. As an individual – I can only speak for myself – I felt very powerful when I was young. I thought: Oh, I have an idea and this idea has power and I can influence things. Even as little kid: I can kick the ball this far! I can reach this shelf! I had this sense of agency moving through the world and it never occurred to me that someone might not take me seriously or this person might think that I have to be accompanied when female, for example. One of my questions is: To what degree are we born with power that is our birthright as human beings, and to what degree do institutional systems of power strip that away from us?

On one hand, it’s kind of a big-R Romantic question that privileges the individual, in terms of the individual having all this big imaginative power and capacity to transform the world. I do have a gravitational pull toward that thinking, but I also grapple with it. I think there are big problems with privileging the individual because it has historically erased the collective and erased certain forms of solidarity. Like with feminism, for example, specifically the idea that feminism is all about individual choice. There’s something I agree with about that, but there’s also a way in which that can be neatly folded into a neoliberal project where it’s like, well, women are liberated now because they can buy shit for themselves. Or women are liberated because they are financially self-sufficient and really, what that means is that more affluent women—often white women—are liberated, and that larger systems of power that oppress millions of people can be ignored because the individual is the focus.

That makes me think about the title poem in the collection, which is concerned with an individual – a female character – and seems to be thinking about femininity, loss, and sexual agency. And violence too. Can you talk about the process behind this poem?

That poem was originally called “Euphoria Takes One for the Team” and was made into a chapbook by Dancing Girl Press about five or six years ago. I was imagining euphoria as a woman, a kind of femme fatale and happiness as something illusive and seductive and sexy, but also kind of dangerous if you seek it out so much. I just don’t think that anyone can choose to be happy. I think that’s a total fallacy. Plenty of people might disagree with me, but I don’t think it’s possible to be like, Well, I choose joy. I feel like this idea that we have the ability – that it’s willful or just a matter of choice to be happy – can be a very harmful way of making people who do not feel happy feel even worse, or feel guilty about the fact that they are not choosing to be happy, like other people ostensibly are choosing to be happy.

So, I was thinking about “Euphoria” as a kind of femme fatale character and that’s what motivated the first section where I’m describing this female character with nice legs and red hair—I was thinking about the femme fatales I’d seen onscreen. Especially during the classic Hollywood period, 1940s cinema. Busby Berkeley from the 1930s also has some really vulgar, raunchy femme fatales that are really funny. I was channeling that type of character and thinking: Where would she go? What would she say? What would happen to her? I was also trying to connect these questions to the idea of being able to choose “Euphoria”—and the futility of that.

Another influence on the poem was the movie Medium Cool, from 1968, that I was shocked that I’d never heard of before. It’s by this director, Haskell Wexler, and it really blew my mind because it was a narrative feature film, set in Chicago, and towards the end, one of the main characters is walking around where the 1968 Democratic National Convention was being held, during the famous protest. It’s this feature film that you would take to be fiction and then this character who is also fictional is walking through the actual protest. I was watching it thinking: This is so realistic! I can’t believe they recreated this protest that was so famous. Of course that protest remains famous for being one of the first times that media came in and was present and documented police brutality. And it had been broadcast on live mainstream TV, so this chant that appears in the poem, “The whole world is watching! The whole world is watching!” was something that had political resonance. People were seeing what was happening during this time period in a new way – their screens were being invaded by images of violence, images of corruption, etc.

That film made its way into the poem because I found out that the scene wasn’t a recreation. They decided to shoot this fictional scene in that space and a riot went out of control. It’s amazing seeing this fictional character actually terrified—because she was, the actress was terrified! There’s this fantastic co-mingling of diegesis and a feeling of Oh no, no, this is reality. I created the Euphoria character in this poem thinking about how she’s in her own fictional world, but then reality encroaches in different ways. There’s this sense of spectacle that surrounds her as a character and the way reality takes her to be spectacle. It was an experiment in form and also an experiment in connecting interiority to more public political questions of class, of violence, of institutional power, etc. The poem also explores my own struggle with depression, which is of course deeply personal. But it’s only in connecting the personal to the public, to the spectacular, that I can even begin to make sense of it.

Throughout the book, you seem to be interrogating notions and presentations of hyper-femininity, but also hyper-masculinity. Why are you specifically interested in the extreme versions of these gender constructs?

I think I’m drawn to them because, personally, I have long embodied traits of the two poles. Growing up, I was a consummate tomboy—I loved fishing, sports, catching bugs, and hanging out with boys. I’ve always been pretty opinionated and competitive, and in the neighborhoods I was raised in, girls weren’t really supposed to behave that way. I say “behave,” but really, I didn’t feel allowed to be that way, regardless of behavior. It’s more constitutional on my part; even if I’m not enacting my opinion or exhibiting a competitive spirit, it’s still usually present. At the same time, I’ve long been enamored of feminine adornment—cosmetics, fashion, jewelry, the whole shebang. Growing up in the 80s, Madonna was a huge influence. Even more so since she was not exactly embraced by my Midwestern Catholic family (despite, of course, Madonna being a Midwestern Catholic!).

I’ve long gravitated toward what might be considered the two poles; it’s the middle I sometimes have trouble navigating. So, I think intellectually, exploring these themes is of import to me. I realize that some of my more traditionally masculine traits—a kind of confrontational spirit, aggression, love of power—are not exactly always admirable! But at the same time, there they are, and I don’t foresee them going away. Similarly, I’m ambivalent about the forces of traditional feminine beauty, but also utterly adore experimenting with its rituals, whether it be a shade of lipstick or style of stockings.

In terms of learning something from these extreme manifestations, I think perhaps it’s how much they can have in common in terms of damage. I think I’m most invested in the harm wrought to one’s own body in the process of achieving some masculine or feminine ideal; rugby and ballet, that sort of thing.

I think insofar as human beings become conscious that they ought to be a certain way, gender-wise, there’s the potential for both hyper masculinity and hyper femininity to emerge in either destructive or productive ways. I see drag as one productive manifestation of these extremes, for example–and more everyday aspects of drag that never hit the stage.

Has the increased visibility and conversations around sexual violence and consent changed or shifted anything in the ways in which you are interested in writing about gender and power?

This book was written prior to the Weinstein scandal and #Metoo, so in no way is any of it directly engaging with that, but I’ve long been interested in sexual power in general, especially how it’s manifested in less obvious ways, by less obvious players (i.e.: not white straight men). With my poem “Invisible Men,” one of the newest poems in the collection, I humorously scrutinize the appeal of “rich white men” as potential lovers, imagining what it would be like if these guys were literally invisible and so never acknowledged. With the punch line of the poem (and I don’t mind if it’s called a punch line, because I admire comedy as having its own poetics), I say, “Please don’t take this personally, but I happen to see right through you.” I think in a way, it’s less about the increased visibility of sexual violence specifically, as it is the increased visibility about just how entitled straight white men tend to be that catalyzed this poem.

I think I am still grappling with questions of gender and sexual power with the #MeToo conversations that continue—and should continue—to emerge. As someone who tends to be the pursuer, the aggressor, I suppose, in certain romantic situations (at least at first), it’s admittedly sometimes hard for me to imagine not feeling like one has the power to consent or deny consent. But that has to do with my own lack of immediate empathy—not the reality of the situation. The more the conversation has grown, the more I’ve become aware of how my own experience—as a woman, a sexual person, and a person who often enjoys confrontation—is not necessarily the norm, and that I need to more consciously empathize with those who were robbed of their power to consent, or perhaps felt they never had this power to begin with. It’s thorny terrain, and I think that’s important to recognize. But I hope more open conversations about consent and power will lead to fewer assaults and better sex–and just a healthier sense of humanity in general.

————————-

Life After Rugby is available from Gold Wake Press, https://goldwake.com

You can find Eileen on Twitter at @Reckless_Edit or at her website, www.eileengsell.com