NOT EVERY DEAD BODY GIVES UP A GHOST: A CONVERSATION WITH ALANA I. CAPRIA

10.04.18

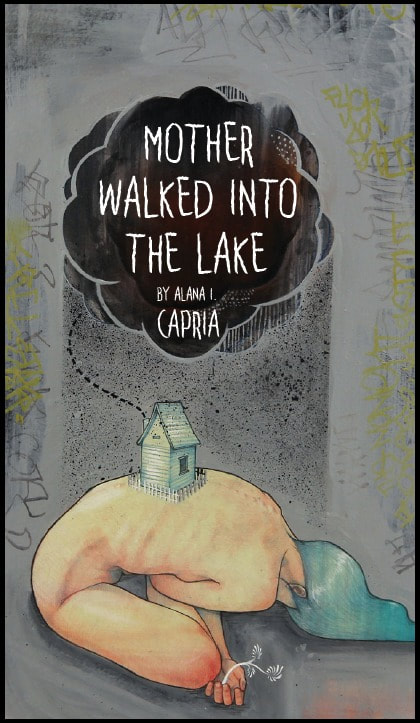

A lot of books are scary, but few fundamentally change the way you see the world. Alana I. Capria’s horrific fairy tale novel, Mother Walked into the Lake, is one of these—an artful feminist nightmare dripping with atmosphere and style, almost supernaturally so. We live alongside a family grieving their matriarch’s suicide, only to find she’s been dredged, alive, from the lake where she drowned. This course of events makes us wonder if she’s been imprisoned with her family or vice versa. Throughout, Mother Walked into the Lake is relentless, unforgiving, compelling writing—it challenges our worldview while simultaneously using fresh language and unfamiliar tropes. In Mother Walked into the Lake, Capria creates something altogether, frightfully new. Films such as They Looked Like People, Antichrist, and Inland Empire come to mind, the book surreally cinematic, but even these can’t match the fervor of Mother Walked into the Lake. This is horror ahead of its time, fully realized yet entirely accessible in 100 pages. A tall order: We need our books to possess us like this one.

A lot of books are scary, but few fundamentally change the way you see the world. Alana I. Capria’s horrific fairy tale novel, Mother Walked into the Lake, is one of these—an artful feminist nightmare dripping with atmosphere and style, almost supernaturally so. We live alongside a family grieving their matriarch’s suicide, only to find she’s been dredged, alive, from the lake where she drowned. This course of events makes us wonder if she’s been imprisoned with her family or vice versa. Throughout, Mother Walked into the Lake is relentless, unforgiving, compelling writing—it challenges our worldview while simultaneously using fresh language and unfamiliar tropes. In Mother Walked into the Lake, Capria creates something altogether, frightfully new. Films such as They Looked Like People, Antichrist, and Inland Empire come to mind, the book surreally cinematic, but even these can’t match the fervor of Mother Walked into the Lake. This is horror ahead of its time, fully realized yet entirely accessible in 100 pages. A tall order: We need our books to possess us like this one.

Alana is the author of the story collection Wrapped in Red and the novel Hooks and Slaughterhouse, both from Montag Press; and the chapbooks Organ Meat, Killing Me (Turtleneck Press, 2012) and Lilith (dancing girl press, 2015). Mother Walked into the Lake was released by KERNPUNKT Press in December 2017. She resides in northern New Jersey with her husband and rabbit.

What follows is an edited exchange of our emails over a few weeks.

Jason Teal: You have quietly dominated independent circles of fatalistic horror since the release of Wrapped in Red and Hooks and Slaughterhouse. Can you talk about the change Mother Walked into the Lake sees for your writing?

AC: I consider Mother Walked Into the Lake to be the most personal of my fiction and definitely the most plot-driven. I wanted Mother to be the kind of story the reader could believe happening, even when it was at its strangest. To balance the realism and supernatural elements was a challenge and I spent over two years trying to get the story right. In the end, the novel’s style was entirely different from anything I ever wrote before and there was such excitement in knowing I was capable of creating something new, both in terms of narrative and craft.

Mother was also more directly influenced by traditional ghost stories. Stephen King’s The Shining and Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House are two of my favorite haunted house novels and in a sense, their sensibilities helped form Mother. The crux of most (all?) haunted house stories is the families’ most buried tensions. The ghost becomes a symptom of these repressed resentments and aggressions. You see this in Mother: Mother is a woman who never fully accepted the strains of motherhood and when she returns from drowning, it is as a vengeful ghost figure, one that forces the family’s closeness so that they can reconcile the truths of the family with the fairy tale.

The use of the ellipses throughout seems especially crucial—I know many writers avoid specific punctuations (the semi-colon, for instance; gods know why). Was the choice to link sections with this punctuation an afterthought? What utility draws you to the ellipsis?

When I was working on my MFA, a large part of my thesis research revolved around Russell Edson’s prose poetry. One of his stylistic quirks was using ellipsis to end a piece, which illustrated that the story continued off the page, possibly forever. I became fascinated with that sentimentality and adopted it for my own. I love the thought that the story has a life of its own that spirals beyond what I could ever imagine.

I also have a more utilitarian use for the ellipsis. I like keeping my writing in a plain text master document and the ellipsis acts as a sort of marker so that in the event of a formatting issue within the document, I can easily restore the paragraphs (I once forgot the password I set for a document and upon getting it open, found that 500+ pages had lost their formatting).

I’m endlessly fascinated by the makeup of the novel—at once feminist, horror, fantasy, surreal, grotesque, comedy, tragedy, and so on. Did Mother’s biology come naturally, or did you set out to deliberately create story alchemy?

Above all else, I consider Mother to be a ghost story, albeit one trapped in a fairy tale world. I have always been a sucker for a good ghost story, especially those that lean towards surrealism. My Halloween tradition is to watch all of Most Terrifying Places in America (it’s eighteen episodes long). One of my favorite Christmas presents to this day was from when I was eight or nine years old and my uncle gave me Harper’s Encyclopedia of Mystical and Paranormal Experience edited by Rosemary Ellen Guiley. The book that inspired me to be a writer at the tender age of six was Christina’s Ghost by Betty Ren Wright (I read so many of her books, especially The Dollhouse Murders, A Ghost in the House, and Ghosts Beneath Our Feet). In light of all that, it’s surprising that it took me this long to finally publish my take on the haunted house. Most of my fiction before Mother has centered on fairy tales.

Above all else, I consider Mother to be a ghost story, albeit one trapped in a fairy tale world. I have always been a sucker for a good ghost story, especially those that lean towards surrealism. My Halloween tradition is to watch all of Most Terrifying Places in America (it’s eighteen episodes long). One of my favorite Christmas presents to this day was from when I was eight or nine years old and my uncle gave me Harper’s Encyclopedia of Mystical and Paranormal Experience edited by Rosemary Ellen Guiley. The book that inspired me to be a writer at the tender age of six was Christina’s Ghost by Betty Ren Wright (I read so many of her books, especially The Dollhouse Murders, A Ghost in the House, and Ghosts Beneath Our Feet). In light of all that, it’s surprising that it took me this long to finally publish my take on the haunted house. Most of my fiction before Mother has centered on fairy tales.

I love dark fairy tales. I have a volume of Grimms’ fairy tales my mother gave me when I was a child and it contains some of the more well-known stores in all their deep, dark forest luster. I watched a fair amount of Disney movies as a child and found that with each one, I was irritated. I hated Snow White and Cinderella, finding them to be wishy-washy twerps. I thought Rapunzel was an idiot, that the evil stepmothers were treated unfairly. I wanted them to fight back. My favorite fairy tale was “The Little Mermaid.” I hated that in the movie version, Ariel was at the mercy of the men in her life. Her companions were all male, her father dictated her life, upon finally becoming a human, she was immediately married. In the original story by Hans Christian Andersen, the little mermaid becomes human but when she walks, it is as though her feet are being pierced by knives. Mermaids have no souls and can only receive one if they marry a human. At the end, the prince rejects the mermaid by marrying a princess, and the little mermaid commits suicide.

It was a relief when I finally encountered Angela Carter’s writing in college. I read The Bloody Chamber and immediately collected the rest of her short fictions (Saints and Strangers, Fireworks, American Ghosts & Old World Wonders). For the first time, it really dawned on me that I could rewrite all these stories I had fundamental, existential issues with and make them what I wanted to see. So I gave these characters teeth and claws, made them bite. That aesthetic eventually found its way into Mother. She wasn’t a saint, she wasn’t a villain. She was just flawed.

Mother was also inspired by a number of contemporary art pieces, including:

1.) La Mémoire Douloureuse by Marc Giai-Miniet.

2.) Haunted Dolls by Laurie Lipton.

3.) The Submarine Wings and Seeds project by Philip Ob Rey.

4.) Oh Sylvia by Caryn Drexl.

5.) Sisters in Silence by Caryn Drexl.

6.) Unos Cuantos Piquetitos by Frida Kahlo.

7.) Asylum Shadow by Herbert Baglione.

8.) The Architectural Collages by Anastasia Savinova.

9.) Maman by Louise Bourgeois.

Do you have a background in visual art? This seems like a great list.

I dabbled in the visual arts when I was young but after college, I started following modern art and medical art websites such as This is Colossal, Phantasmaphile, Street Anatomy, and Morbid Anatomy. I don’t know if I could write without the visual arts. There are many times in the writing process that a story spirals out of an image, whether it exists solely in my head or is an actual piece. That union between the written word and visual art feels natural.

The book is so filmic. It’s almost as if you had a film editor consciously select scenes for inclusion from a larger reel. I’m curious: If you had to pick one working director to adapt the book for film or series, who would you choose?

I unfairly think of Guillermo del Toro but realize he’s already produced something about motherhood and possessive relationships, so maybe he’s out.

I have a few contenders: Osgood Perkins (I Am the Pretty Thing that Lives in the House) and Nicolas Pesce (The Eyes of My Mother). The films focus on a gloriously quiet horror that permeates and festers. There’s a little slip of reality, that uncomfortable feeling that the world is suddenly askew. Each contains its own haunting and a woman trying to quell the horror. I think either of these directors could turn Mother into something gorgeously horrific.

I Am the Pretty Thing was gorgeously surreal in parts, as well as effective in maintaining an atmospheric tension that became almost claustrophobic. In The Eyes of My Mother, the main character is haunted by her mother but that haunting is entirely self-inflicted. Both of these characters are alienated from the rest of the world; they do not know how to fit in. And so, they adapt as best they can, with one living in constant terror and the other opting to do the terrorizing. All in all, I think I would give the win to Pesce.

Also on the short list: Jennifer Kent (The Babadook) and J. A. Bayona (The Orphanage/El Orfanato), also for the reasons listed above, but thereby disqualified because, like del Toro, the movies are already mother-centric.

There is a fearsome quality with which Mother portrays family coping with individual mental health:

[Mother] wanted us to cough just as she did, as if sharing the disease might create solidarity between her and us […] If we were as sick as Mother, then the sickness became normal. If the sickness became who we were, then there was no reason that we could not all be together…

As you know, mental health doesn’t often get a fair shake in horror fiction, which too often shades its players as Other, and disturbed. Yet, in Mother, the family siblings, and even Father, hold on despite these dire circumstances as the unit tries to function anew. This, unexpectedly, leads to some heartwarming scenes contrasted with terrifying “games” of control, such as hide-and-seek. Why did you decide to write this major theme for the book?

Depression runs in my family and I am one in a long line of relatives to be afflicted. When you have chronic depression, that depression becomes its own state of normalcy. At a certain point, when a person is largely one way or another emotionally, then that emotion becomes the baseline. Any emotion that deviates feels strange by comparison. If you are depressed ninety percent of the time, then happy the rest of the time, the happiness is what feels unnatural, because it isn’t commonly felt. Conversely, if you are usually happy, then suddenly depressed, that depression will feel more overt, because it is a foreign emotion.

In Mother, a large question is: Which mother is the real mother? Is it the mother who walks into the lake or the mother who comes out? Is it mother when she’s happy or mother when she’s sad? And the question the siblings have to ask themselves is: Can we accept mother no matter how she is? If she no longer fits into the box of their expectations for her, is she still the same person? That is a struggle so many people go through. Can they be accepted by those around them for deviating from the norm or is the change too much? Maybe the question that really needs to be asked is: Why, when someone refuses to act the way we want, do we feel so afraid? And so, that is the crux of Mother: Can we accept the fact that those closest to us aren’t perfect?

Can feminism and horror be easily reconciled? Critiques of the slasher and thrillers dealing gratuitous violence on women come to mind as scarification of the genre (of which I’m a complicit reader). I’m thinking of your earlier works as much as Mother here. What draws you back to horror?

I believe that feminism and horror can go hand-in-hand, although it takes a fair amount of subversion of the genre. In so many genre stories, female characters are meant to be ruined and that ruination is all they can aspire to. It’s a belief that characters will not act until there is a woman to avenge, that in order for the viewer/reader to care, the woman must be savaged. Without victimization, the plot would never be set in motion. Often, it is violence for violence’s sake. It is along Edgar Allan Poe’s thinking that nothing is more poetic than the death of a beautiful woman.

My fiction has always focused on women rebelling against preordained roles. Princesses don’t look for the princes to save them but to be their next meal. Little Red Riding Hood destroys just as much as the wolf. Women’s reproductive organs become anthropomorphic and no longer obey the commands of the body. Mother walks into the lake because she refuses motherhood. There is a horror in rebelling, in rejecting traditional roles.

I write horror because I like to be scared. I like looking over my shoulder, feeling a sort of tightening in my gut from terror. But I prefer haunted house horror because while a ghost is considered scary, it is a removed kind of scare. Not every house is a haunted house, not every dead body gives up a ghost. But it’s the fear that horror resides in the home. How terrifying is it to imagine that your home, even your body, decides you’re the enemy. It’s the horror of: What if there is no safe place? What if those very things we take for granted—home and body—go wrong?

You book scared me but I’m excited to revisit it a month from now, maybe even earlier. What’s the scariest book you’ve ever read?

The scariest book I’ve read is The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty. I was raised Catholic and so anything related to demons was a no-no. Just based on the subject matter, The Exorcist was nightmare fuel. There was a long period after reading the novel where I couldn’t look at the staircase in my house because I was so paranoid that I would see my little sister descending it while in a backwards spider crawl. I hated the cover as well. It was a sepia image of a woman twisting to look at the reader and its eyes were more like impressions, giving the face an unwelcome blankness. Eventually, my mother begged me to throw the book out because it’s very presence in the house terrified her.

My scariest nonfiction book would be From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death by Caitlin Doughty. It’s an exploration in death rituals around the world, as well as cultural differences in regards to our treatment of the dead. I don’t think there’s anything scarier than being confronted with your own mortality. It’s so easy to imagine that death is this far off thing but really, who knows? It can just as quickly be in a flip of the page, a sip of soup.

Death rituals! What an intimidating subject. Not that it’s required, but would you ever write nonfiction?

I have written nonfiction professionally in the past. My freshman year of college, I wrote movie reviews and general musings for a small Hudson County newspaper. I also spent that year working as a staff writer for my college newspaper. For the remainder of college, I worked as a staff writer for a South Bergen County newspaper. I mostly did write ups of various board of education and municipal meetings (as with most small towns, a few of the dealings were on the shady side). I dabbled in more personal nonfiction but I’ve never liked writing outwardly about myself. I prefer putting bits and pieces of real life into my fiction to the point that it’s warped beyond recognition. Fiction is my comfort zone.

The collective “we” perspective infests Mother with a rhythm and cadence unmatched by, perhaps, a different book drawn only from the Father’s point of view or that of Mother. And still, we hardly see the children separated from one another—Sister, Brother, and the narrator seem to exist as three parts of the same person, until one chaotic scene where Mother has been frantically happy and our narrator reflects that “motherhood was certain” for herself. Was there something Freudian underpinning this number of children, the number of family? I noticed that the children were each mortally concerned with their cosmic insignificance at one point, wrestling with origins of the universe.

The siblings serve as an homage to my relationship with my younger sister and brother. Our parents raised us with the mentality that no matter what, your siblings always come first. You protect them, you’re loyal to them. We’ve always gone out of our way to stand up for one another. The siblings in Mother reflect that dynamic.

The novel also meditates on personal identity. If you strip away all the relationships in your life—if you are no longer a son or daughter, a sister or brother, etcetera—who do you become then? That was an idea I wanted to explore in the novel, but on a grander scale. Who are the siblings when they are entirely alone? The scene where the siblings narrate creation myths was one of my favorites to write. I’ve always been fascinated by the largeness of space, this idea of distances so great we can’t even fathom what they mean. At least for me, to think of it for too long becomes overwhelming. I like that the siblings shared that fear together and strove to comfort one another when it became too much.

There are so many visceral images in the text: blood flowing out of bodies as well as characters facing very real, and self-inflicted, danger, because they cannot, or will not, leave the house. To be blunt: Your writing is not for the squeamish. So I’m wondering, with this emphasis on physical horror, along with psychic and supernatural elements, how did you approach refining imagery for the manuscript?

I come from a short fiction background and so that’s the mentality I have when working on my novels. I approach long projects as a patchwork of smaller, self-contained bits. It’s the only way I can sustain the momentum for the duration of the project.

The first drafts of Mother were very long, about 80,000 words. It’s a very heavy book, dense and graphic. A story like that is overwhelming when it’s so long and so I sliced it until the final manuscript was around 32,000 words. There are a few scenes that are reminiscent of one another but that was a narrative choice. I think that people have a tendency to fall into patterns (I find routines comforting and I’m sure I’m not alone in that) and do the same things repeatedly. I wanted the novel to express that.

Along these lines, can you tell us what you’re working on now?

Presently, I’m working on a novel revision for a project I started while drafting Mother. This project has had several incarnations so far, none that I’ve been completely happy with. An excerpt from one of those drafts was published in The Avenue Journal‘s Woman Issue. To explain it vaguely, the story is about a codependent, superstitious, death-obsessed couple who lock themselves away from the outside world. The female of the couple becomes pregnant and then, everything goes to hell.