My Kingdom for a Sexologist

16.07.12

It is not knowledge we want from the internet, after all, but the stability that comes from never having to question something again. It encourages a kind of reverse fact-checking process wherein irreducible phenomena are atomized by science, reconstructed, and finally installed into the world of canonical fact. It is a nonsense space trying to form itself into a stable info-polymer.

In 1886 Richard von Krafft-Ebing1 prefigured many of these tendencies with his book Psychopathia Sexualis. “The propagation of the human species is not committed to accident or to the caprice of the individual,” he wrote, “but made secure in a natural instinct, which, with all-conquering force and might, demands fulfillment.” In sex Krafft-Ebing recognized a volatile subject that triggered the most parochial instincts in people. He hoped his work would “save the honor of mankind before the Court of Morality, and individuals from judges and their fellow-men. The duty and right of medical science in these studies belong to it by reason of the high aim of all human inquiry after truth.”

Psychopathia Sexualis offers a model for how information and authority disseminate through culture by using science to create the illusion of certainty about something both mundane and frighteningly beyond reason. Sexual inquiry was not a new subject in 1886, but there had never been a definitive scientific body of knowledge for it, and so Krafft-Ebing put forth his work as an effort to go beyond the sentimentality of artists and philosophers, while cohering the fragmentary studies of other scientists––an effort that would soon formalize into the discipline of sexology.

More than a century later, sexology is a much-changed discipline, but Krafft-Ebing’s instinct to retreat to clinical objectivity as a way of claiming authority before the “Court of Morality” has been prophetic. It serves as precursor for the psychopathy of internet discourse, a vast anthropological archive of the tens of millions of isolated kingdoms of egos cached into oblivion.

The objectivity of science can be a mediator in these clashes, and so we appeal to it to strengthen our own habitual kingdoms of fact. An internet jokes become a “meme,” a phrase invented to describe the transference of behaviors within a culture, or between cultures. Disparate news stories are yoked into Top 10 lists. Media figures have their lives cherry-picked, turning them into digital eidolons to whom we can play-swear our allegiances. And scientific research is translated into paradigm-shaking headlines that tickle the anxious borders of our plebeian book-learning.

The internet transforms writing from a medium of exchange into one for asserting authority. It enables combat between presumptive power figures, a platform for indignant attacks on the ausländer preaching heresy to the unguarded flock. Hypothetical inquiry is an invasion into someone else’s subconscious, and it registers as a claim to the crown. In this setting, sex is the perfect subject because of its universality and the impossibility of reducing it into any singular state of experience. Sex poses nothing but questions, and it leaves us all feeling capable of speaking to the subject with at least some general sense of authority.

To wit, sexology as a brand has flourished on the internet. This is not to say that the internet has been especially helpful to the practice of sexology. Sex research has undergone dramatic change in the last 100 years, but it remains a fragmentary undertaking split up across a number of larger fields like biology, behavioral science, public health, and sociology among others. Curtin University in Perth, Australia offers postgraduate degrees in Forensic Sexology, the University of Quebec in Montréal offers a Masters Degree in Sexology, and the privately owned American Academy of Clinical Sexologists offers a Ph.D in Clinical Sexology for people wishing to practice clinical sex therapy.

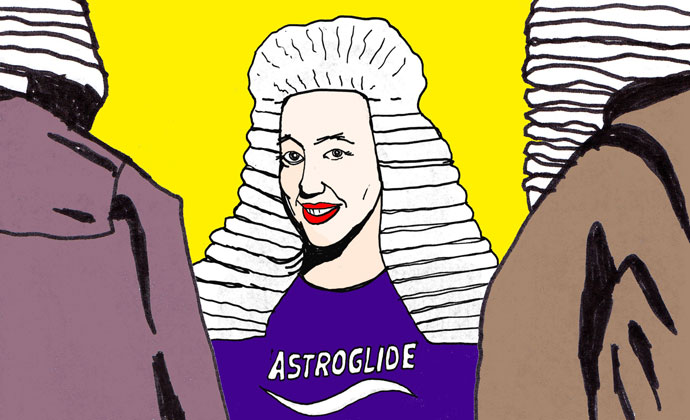

Sexologists are more familiar as “sex experts”––a title that many use synonymously with sexologist––who mix social advocacy with sprinklings of science. Yvonne K. Fulbright has written sex columns for The Huffington Post, FoxNews.com, and Cosmopolitan. She also serves as a “Sexual Wellness and Relationship Ambassador” for the lubricant brand Astroglide. Fulbright holds a Masters in Human Sexuality Education from the University of Pennsylvania and a Ph.D in International Community Health Studies at NYU. She’s also author of a number of sexual self-help books like The Best Oral Sex Ever (in his and her varieties), Sultry Sex Talk to Seduce Any Lover, and The Better Sex Guide to Extraordinary Lovemaking.

Fulbright’s interest in studying human sexuality is inextricably personal. An immigrant from Iceland who arrived in the United States at age 10, she found a jarring difference between the attitudes of her classmates and parents. “I was the first girl in my class to hit puberty and I was getting a lot of attention from that, some mixed messages,” she told me in a phone interview. “As I got older and heard other people’s stories about what a traumatic time puberty was, especially with females who developed early or who developed late––in both cases they’re dealing with negative messaging and negative experiences.”

Though Fulbright is academically trained, her work is sometimes hard to separate from her peers who lack comparable credentials. Ducky Doolittle is a popular sex educator who has appeared on NPR, The Howard Stern Show, and is a regular speaker at college campuses around the country. She is a certified Sexual Assault and Violence Intervention Counselor and has trained with Planned Parenthood on STD prevention and comprehensive sex education.

The line blurs even further with Sarah White, who has founded a therapy practice based on the presumption that nudity makes it easier for patients, primarily male, to engage in the process. While lacking clinical credentials––she holds an undergraduate degree and says she is collecting research for a dissertation on naked therapy––White features a testimonial for her service from Alan S. Liu, an MD in Child, Adolescent, and Adult Psychiatry, with whom she shared a patient.

What joins these figures is not their work, per se, but the needful curiosity inside their audiences, propelled always to seek out facilitators to answer questions about a subject for which they want a coherent authority. This need within us has spawned a major industry of idea-translators who live in the plain-spoken borderlands between the mathematic truth of the universe and the digestible metaphors of folk wisdom. In this, sexology is no different than physics, economics, or neuroscience, empowering writers like Jonah Lehrer, Malcolm Gladwell, Jane McGonigal, Steven Levitt, and Stephen J. Dubner to explore secret truths that we always suspected were there but lacked the breadth and vocabulary to discern on our own.

The chemical perfection of ketchup or the neuroscience behind World of Warcraft are suitable subjects for extrapolation because their effects are so recognizable. Ketchup is good because its balance of salty sweetness and vinegar tang pleases a broad range of the flavor spectrum for many people. World of Warcraft feels good because it is larded with discrete and achievable goals that play on a person’s self-esteem. These qualities are self-evident without further embellishment from molecular arcana. But it is precisely because the conclusions reached through deference to scientific authority will be so uncontroversial that makes the process hypnotically appealing.

The forced juxtaposition of the obvious and the mystical is the only abiding truth of the internet; it is the motor behind its perpetual incoherence and disorder. People communicate alongside one another, relying on a near infinite reserve of iconography that can be taken to mean almost anything when forced out of context. In this environment we have an instinctual need to seek out authoritative mediators that can delimit the possible fallout from confrontation. The self-conscious suspicion that our need for authority is itself a weakness adds hostility to these encounters, in which we must both strip down the false prophet and confess our vulnerability to false prophets in the first place.

In a diary entry written in 1942, George Orwell decried the prevalence of ad hominem hostility and intolerance in the England’s media, based on the myriad interpretations of a speech given by Lord Beaverbrook, the country’s Minister of War Production. “Nowadays, whatever is said or done, one looks instantly for hidden motives and assumes that words mean anything except what they appear to mean,” Orwell wrote.

He rather neatly prefigures the sarcasm-driven indignation complex, more concerned with condemning alternative views than synthesizing them. “Everyone’s thought is forensic, everyone is simply putting a ‘case’ with deliberate suppression of his opponent’s point of view, and, what is more, with complete insensitiveness to any sufferings except those of himself and his friends.”

We don’t need to know what monsters like these would have done with the internet. We are those monsters and we are everywhere, seeing villainy in one another, suppressing the validity of each other’s views and experiences, struggling for a form of authority that the internet is finally incapable of giving. It only gives us one another, a redundancy accelerated by computers and smartphones. We can never seem to survive without falling back on the Court of Morality, whose judge’s certification process has now been transformed into a digital parade of authorities waiting for their chance to propagate someone else’s peace of mind for their own purposes.

__________

1 Full name: Richard Fridolin Joseph Freiherr Krafft von Festenberg auf Frohnberg, genannt von Ebing.