More Than Love & Joy: A Conversation with Hanif Abdurraqib

13.11.17

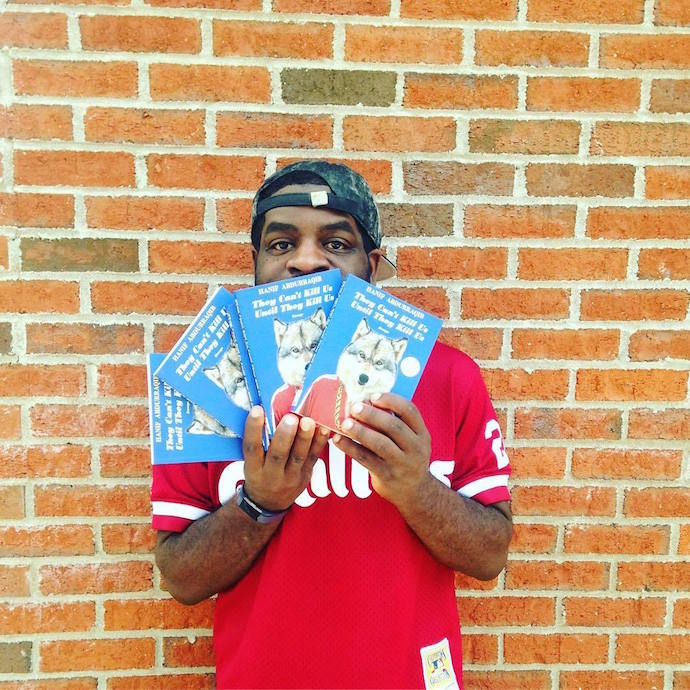

In her foreword to They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us (Two Dollar Radio, $15.99), Eve L. Ewing writes, “this book almost makes me believe in things I’d thought I’d given up on.” In a year that’s felt like a century, hope is hard to come by. Hanif Abdurraqib doesn’t promise us anything beyond brilliant flashes of light in a dark and complicated world, but he does it with such generosity, such grace that we might not deserve it.

Moving seamlessly from Fall Out Boy to Nina Simone, from Bruce Springsteen to the death of Mike Brown, Abdurraqib centers this masterful collection of essays not only around music and the way it’s shaped and carried him through life, but the tiny sparks that help us survive. “Joy, in this way, can be a weapon — that which carries us forward when we have been beaten back for days, or months, or years.”

I spoke to Hanif this fall about his book, elementary school music lessons, and Lester Bangs.

JF: This is maybe not the most professional way to open an interview, but, after your music teacher told you your face was wrong did you quit playing the trumpet? I am asking because a similar thing happened to me and I’m still mad about it.

HA: Yeah, I think I kind of kept playing for a while out of spite, though. I actually open the Tribe Called Quest book I’m working on with a longer version of that story. It was my lips, he said. My lips were too big to play the trumpet. My father stormed into his classroom during parent-teacher conferences with a handful of records, all black horn players with big lips. When I was young, I was foolishly embarrassed by that moment — my father storming into a classroom like that. I was only maybe 11 or 12, and so I think I just had this impulse of “I’m being embarrassed by a parent.” Now, I think I look back and realize that my father was defending not just me as a trumpet player, but also the idea of the black musician, particularly from his era, who had been denied and denied and denied and still had to find a way. It was my father’s way of saying “you won’t do this to my son.”

So, I played trumpet for a few years after that, but I was never particularly good at it. I think some people are truly born into a relationship with an instrument, and I was definitely not born into any relationship with a trumpet. I didn’t have the breath for it, or the coordination it took to effectively pull it off. I did play a pretty good version of “Autumn Leaves,” though it took me a year to get it down.

You were much braver than I was. I just never went back. A better question that relates to both “Nina Simone Was Very Black,” which, like this whole book, is beautiful and insightful, and They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us as a whole, is what is it like to write about your very specific experience, knowing people (like me, right now) will project themselves onto it in a way that can erase the essential point you are making?

Thank you for your kind words. I don’t know if projection by itself erases the point, you know? I mean, I think there is some stuff in there that was written to open a wide door for folks to enter a similar space as I was in/am sometimes still in. I think the work of the reader is to know which room is beckoning you as an active participant and what room is perhaps simply beckoning you as a listener to those who might be more suited to be active participants. The essential point, I hope, has many lights pointing to many paths. And, sure, they all aren’t for everyone. But there comes a point where that part is out of my hands, and I have to trust whatever might be behind that projection. Your music teacher’s slight might not have been motivated by race, though perhaps it was motivated by another identity you hold that still was driven by a discriminatory stereotype (the same music teacher who told me my lips were too big to play trumpet told a girl in my class that girls were usually “not built to play tuba,” so I mean it’s all so much.) I’m intimately interested in the intersections we allow ourselves when we do understand that all of our various cages aren’t rattled by the same ills, but there might, in fact, be an overarching ill that rattles them all the same. And we can come to that conversation understanding that one doesn’t entirely have to be worse than the other. I hope for careful and gentle readers who aim for that.

You do a great job of cracking that quest for intersectionality open a little wider in “I Wasn’t Brought Here, I Was Born…” when you’re talking about trying to be invisible at punk shows and watching girls get pushed around, the way that feeling “othered” seems to give some people the freedom to ignore larger issues. “I don’t remember the first time I made an excuse for being a silent witness.”

Yeah, I think often about this. I was just in LA and I was talking to one of the old punks I used to go to shows with, and we’re both grown ups now, and we’re both trying to be better than we were in our youth, but I think we still kind of reveled in what invisibility afforded us back then. I think when someone is inside of a world in which they’re either invisible or they’re a target, invisibility really feels like a blessing. So much so that it isn’t exactly inspiring to make yourself visible in the name of defending the other people who are targeted and not as lucky as you might be. I think this is all something that it is hard to unpack as someone 17, 18, or 19. Even when punk sells itself as this familial thing where no one gets left behind. It is weird when vanishing feels like survival.

Or if you’re visible, you want to be visible as something the people like you aren’t. “I’m not like those other girls, I can take a hit. I’m not like those other guys, I can take a joke.” You don’t always realize when you’re that young what you’re trading to fit in.

Well, yeah but I also think that when we’re young, it’s hard to imagine a violence more jarring than not fitting in. I have surely felt that as an adult at times, of course. But in youth, it is so massive. Sure, there’s the simple out of “kids are mean,” but it’s a bit more than that, isn’t it? It’s also kind of the suddenness of having to figure your shit out, often with a large audience of parents or classmates or potential crushes. I hope to never stop having to figure my shit out, but I can see the path a little bit easier now that I’m over a decade removed from my wretched and beautiful adolescence. But we sacrifice a lot in the finding of Our People. And I think it’s hard trying to find a place to fit in, and it’s sometimes harder to know when you’ve already found it.

I know Lester Bangs has had a big influence on the way that you write about music, and you mention “The White Noise Supremacists” in that essay. I recently re-read it, and it made me think of how naive I was the first few times, thinking the racism he was talking about was a thing of the past.

Yeah, Bangs is really important to me and I think about that essay a lot. Mostly, I think about how if that essay came out today, it would be torn apart. I mean, it has some flaws in it, surely, and it’s written in a way that I think the critical space couldn’t handle a white dude writing about race today. But that piece came out in 1979, when far fewer white people were able to not only articulate the flaws on these music scenes, but also able to name themselves complicit, and name the things they’ve done wrong in the past. There’s a real section of that essay where Bangs is reflecting and feeling shitty about himself, and he doesn’t dress it up. It presents itself in a kind of raw manner. He lays it out: “I’ve fucked up and I feel shitty about it.” And I don’t really know how I want people to address the ways that they’ve fucked up, but I know that I’m tired of public apologies that feel like they’re serving the public more than the harmed parties. And so I appreciate the parts of that essay that really feel like Bangs grappling with his complicity in these spaces and scenes that had gotten to the point(s) they’d gotten to with racism and prejudice. I think that there isn’t a whole lot that has changed if we imagine the heart of the essay as really being about using racism to project a type of cool. The racism may take some different forms, and sometimes not be as overt as white people calling themselves “niggers” as a token of cool (let’s not forget the infamous photo of Bangs in that “Last Of The White Niggers” t-shirt…) but what the essay was picking at still feels highly relevant.

There’s something in the tone of that Bangs essay that feels sincere in a way that a lot of contemporary public apologies don’t. There’s a performative aspect to the way that we talk about what’s going on that rarely feels more than superficial. You touch on this in “They Will Speak Loudest of You After You’ve Gone,” which covers so many things so deftly in five pages, that it’s difficult to describe. It crystallizes around the myriad ways that white people fail people of color, the 2015 Charleston shooting, and what it is like to wish for violence while understanding it isn’t the answer.

I distinctly remember wanting Dylann Roof to die, and then feeling guilty for wanting Dylann Roof to die, and then feeling shame about my guilt. I know that essay maybe seems like it centers on what it was like to be black in the Northeast among a sea of Well Meaning White People who cared about issues broadly, but not people intimately. But mostly, I think of that essay as me grappling with the complexities of American Punishment. I am not a believer in the death penalty. I think our prison system is deeply flawed on a structural level. How can I reconcile these things with the anger I felt about Dylann Roof? If I allow myself to be governed by my anger, is that a failure? Do I then take on one trait of that which I am fighting against? In the times I write about in that essay — times when I was made to feel invisible in a community I was paying to live in — when people applaud restraint but not question the landscape that so consistently demands it. I think about those times. Really, it’s a negotiation of the emotional response, or an understanding of what it is to believe in violence. For me to say “I don’t believe in violence” may sound nice or placating for the right people, but I have closed my eyes and wished Dylann Roof dead because grandmothers were gunned down in a church next to their grandbabies. I have watched a video of Richard Spencer getting punched in the face and flippantly laughed. I have, in my lifetime, balled a fist and thrown it because in some places, no one makes a fist unless they intend to throw it. So, really, though whiteness was perhaps a lens for entry, what I was really trying to unravel is what I’ve found myself unraveling for the past two years: what it is to believe in violence, but not pray to it.

In “Serena Williams and the Policing of Imagined Arrogance” you say, “There really is no measurement for how America wants it’s Black athletes to be. Oftentimes they are asked to both know their greatness and know their place at the same time….” It’s something that shows up in “It Rained In Ohio On The Night Allen Iverson Hit Michael Jordan with A Crossover,” too, that we spend as much time, maybe more, trying to control the expression of our Black heroes as we do in awe of their brilliance.

Yeah, I love Allen Iverson. I mean, I love Serena as well. I maybe love Serena in a way that feels more like I am an awestruck viewer of someone entirely untouchable in all of the most exciting ways. Loving Serena is like staring into the sun. Loving Iverson — particularly for me as a kid — was a really affirming thing in a lot of ways. He was small, and I was small. Though our smallnesses differed — he was small for the NBA and I was just small for every walk of life. I also really appreciated how Iverson — when faced with shifting his image to go along with the NBA’s newfound respectability — just said “no thanks.” I was really impressed with that. I’m a different sports fan now than I used to be, but I’m still more interested in narrative and personality than I am in anything else. I sometimes think that I get so invested in sports for the storylines and only slightly for the action. And so Iverson, Williams, and the vast many others like them — their expression of self is, to me, as thrilling as what they do in their respective sports. It’s kind of all tied together, obviously. If Serena didn’t win so much, all of the stuff that makes her cool would maybe not matter. If Allen Iverson didn’t represent this perpetual and resilient underdog narrative throughout his entire career, him wearing gold chains during press conferences wouldn’t mean as much. Still, I find myself interested in the story of the hero inside of the hero.

They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us is divided into six parts by short, numbered pieces about Marvin Gaye, centering around his singing the national anthem at the 1983 NBA All-Star Game. What made you think to structure the book this way?

Well, a funny thing about that piece is that the way it sits in the book is its natural state. That is an early version of a piece I wrote about Marvin Gaye and Patriotism, which came out in Pacific Standard last summer. In the original format, it was broken up in sections, like the ones that open each section of the book. We couldn’t run it like that when it published, in part because it was a little hard to follow. But I kept a copy of it in its original structure, mostly because I had been working on some Marvin Gaye poems, and I figured I could find a way to insert that narrative into one or something. I keep far too much writing, I think. There’s this idea I have that I’m waiting for the work to tell me that it’s done with me. I don’t decide when I’m done with the work. This was one of those things. I wanted that Marvin Gaye essay in the book, but there were such distinct themes in those vignettes, and they all sort of spoke to the overarching touchpoints I saw in the book: triumph / fear / loneliness / violence / joy / a reluctant and always-shifting patriotism. Marvin Gaye was so fascinating in that he contained so many complications and it truly felt like the music was his way of working them out of his body. Even the songs about sex aren’t really about sex as much as they are about seeking out an opposite of emptiness. “Let’s Get It On” is this patient, always building ride. And, sure, that’s sexual. But it’s also about drawing out a moment in which someone is present with you. It’s about drawing out a night in which you are not alone. I don’t know. I could talk about Marvin Gaye for hours and I’m sure it wouldn’t be fulfilling to you, or perhaps not to any of the readers of this. But I think what I’m mostly saying is that I looked at that old essay, in a folder where I pile my discarded ideas. And it told me how it wanted to live in the world. Each section of the book echoes a different part of Marvin — a different complication that I found myself wishing he could have lived long enough to unravel.

“Surviving on Small Joys” is both the title of the last essay in the book, and a sort of unifying theme throughout your work — not just in this collection, but in your poems, too.

You write, correctly, “I want to be immensely clear about the fact that we need more than love and joy.” Despite the weight of that knowledge, you manage to bolster that joy in your work, to keep it above your head as you wade through sad and terrible things.

I think the thing I’ve charged myself with is the understanding of feelings as more than just one thing. I no longer imagine grief as only grief, or only something to try and claw my way out of as quickly as I can. I spent a lot of the last year sitting in the direct center of a lot of unpleasant emotions. And, sure, I’m glad to be out here on the other side of all the shit. Of course. But I learned a lot by sitting in my own sadness and choosing not to move. I learned that sadness isn’t only sadness. There is a joy in the sadness that pulls your ship closer to another’s sad ship and lets a newer or deeper relationship bloom. There is a joy in a darkness that passes over you and forces you to sit searching out only your own reflection. Sad and terrible things are sad and terrible things, of course. But I think I’m also talking about them as vehicles. I can’t cast off all of the accidental joys I’ve been carried to on the wings of sad and terrible things, even if I don’t acknowledge those joys in the moment. I’m interested — intensely — in the feelings resting underneath the feelings. In the emotional orchestra, I’ve spent far too long imagining joy as the most silent instruments in the arrangement. The ones I have to strain to hear. I’m trying to move the band around.