Moleskin(e) Deep

03.07.13

Moleskine. The needless “e.” One remembers Georges Perec, salutes his unwavering ways. A vowel that fucks up the pronunciation, renders it variable. And, more importantly, it fucks up the fantasy. Moleskin. How much better. Just the word, perfected by guillotining the “e”––and the things it now, as amputee, settles near––signals fetish, adjusts a particular frequency. It conjures appetites that make one grovel in search of their impossible fulfillment. (Is it just me?) It feels like something that can be slotted between fur and foreskin, between the stump of contemporary experience and the phantom limb of richer lives, between metaphor and metonym when these learn to magically animate exercises that expand human behavior past stultifying collective norms. Moleskine. Moleskin. To know that, e-less, hacked and cauterized, it shares its name with a piece of adhesive cloth used, in prude quarters, to cover the genitals in the filming of nude scenes only infuses it with a more tawdry spirit. In short, Moleskin sounds like something that, in a certain mood or reeved up enough, one should want to lick and lap, to choke on, rather than write and doodle in. Although, if one burns enough time thinking about it, the pressed and smeared and mashed pulp––always a smudge or a Freudian-in-the-room away from becoming a perfect analogy for the fecal––at the heart of the Moleskine journal may just make chasing after these “legendary notebooks”® all the more perverse, vindicating the anti-Perecean “e.”

Of course the Moleskine notebook, our contemporary simulacrum of the ubiquitous personal journal of avant-gardists of all stripes, indispensable testing board of ideas, is really a fetish in a completely different way: namely, in sustaining the illusion that special notebooks are placeholders and extensions of a subjectivity that can still maintain profound engagement and draw deep and inspired insights from the world we’ve been sentenced to. More than this: it fetishizes the idea that there are still both a subject at all in the old sense––the Enlightenment’s autonomous “corner store of consciousness” to the supermarket chain of the corrupted psychodynamics of the 20th century and ours, as Frankfurt School scrooges may have put it––and a world in the sense of a series of social and institutional arrangements (or at least a deep desire and fight for them) based on the drive toward shared emancipation from natural peril and artificial structures of unfreedom, and the maintaining of material conditions and social relations that don’t atrophy experience incessantly. Neither, of course, seems to exist any longer.

Unlike basement fetish economies that can sometimes teach us to slip the heavy manacles of our conditioned bodies, the Moleskine notebook––the personal notebook in general––is a sadly conservative instrument. It’s one of the ropes we use to try to keep the last vestiges of a by-gone world from drifting beyond our horizon. The saddest thing of all is that the blisters from pulling index only energy spent in projection and not, as hoped, in preservation. It’s a refusing to let go of what isn’t there anymore. This is not to say that one can’t handle of Moleskine notebook with some grace, be ready to draw it with injudicious panache at any moment from a backpack or a coat pocket and furiously jot something brilliant and innovative in it. It just means that to sport it properly requires a certain cultivated decadence, a finely tuned sense of cruel irony, aimed particularly at oneself.

Misgivings aside, I couldn’t help but be intrigued––and slightly nauseated as it happens more and more when hearing of these cross-promotional follies––when I heard that Moleskine was producing a series of books or “notebooks” with contemporary architects. Not that architects were being invited to suggest new designs for notebooks or ways for them to disappear in a dignified way, but that these new notebooks, respecting the company’s well-known design, where going to be filled with material relating to and produced by contemporary architects. A fetish-figure vesseled in a fetish-object. They would be, I imagined (rightly, sadly), little monographs disguised as notebooks, with introductory essays and the obligatory interview, in a series un-inspiredly called “Inspiration and Process in Architecture”––a series, edited by Francesca Serrazanetti and Matteo Schubert, that “emphasises the value of freehand drawing as part of the creative process. Each volume provides a different perspective, revealing secrets and insights…” And so, a bit masochistically, I asked to be sent a couple to review––one dedicated to prominent Mexican architect Alberto Kalach and one dedicated to international superstar Zaha Hadid.

Kalach––of Vasconcelos Library fame––fell for it. He turned his Molsekine into a reproduction of a sketchbook, into a collection of his ideas at their larval stage, urgently captured in furious lines and ink washes. En plein air sketching is here given a potable oxygen tank so that it can take temporary leave from its deathbed. This is not to say that there aren’t some interesting sketches in the notebook, or that they don’t help better understand Kalach’s architectural production and his relationship to “a broken city, like Mexico City,” or flesh out a fascination with vegetation as architectural element and inspiration, or sense an excitement with spherical structures and island-like, doughnut-shaped forms.

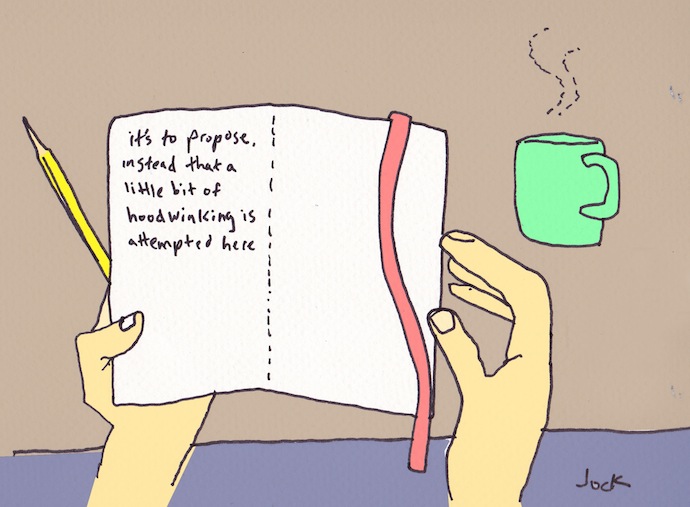

It’s to propose, instead, that a little bit of hoodwinking is attempted here. We are offered a “notebook” as if it was this transparent thing, a real point of contact between thinking and its graphic representation, between the blobs of nascent ideas and the kneading of them into proper shape; as if the hasty graphite line could still be automatically endowed with an irrevocable particularity and the sketch was nothing less than an expression of the dynamic exchange between intuition and execution, between the abstraction of the epiphany and the sensuality of the line. Kalach: “I draw and draw until the idea is clear. There is no room for interpretation.” It’s almost enough to make one run out to the thrift store in search of Herman Hesse novels.

The exercise of generating these “notebooks” is pedaled as if there weren’t layers of mediation and diverse intentions, often unrelated to thinking or drawing, at play here; and as if these layers didn’t convex the mirror and distort the portrait that is supposed to be on offer. Why not acknowledge, just for starters, in the smartly oblique way that this can be done, the central role that promotional value plays for both Kalach and Moleskine in this project? One brand adding value to another on a two-way street. A merging of cultural capitals to see if together they generate new effects and new profits. Little else is really happening here. The audience for these “notebooks” is not so innocent as to be shocked by the fact that there is about as much authenticity in the assembling of them as in any number of architectural projects that populate our cities, and it’s certainly not innocent enough to think that the motivation here is an unmediated view into Kalach’s “creative process”––whatever that could be these days.

Zaha Hadid, in stark contrast, produced what is virtually a catalogue of her paintings––both those made by hand and those rendered with digital imaging software. (There are some supplementary texts interspersed that read like nothing if not exhibition wall labels.) Although I’m no fan of Zaha Hadid’s paintings as paintings (Hadid: “I’m not a painter––I have to make that quite clear”), since they look to me like minor league versions of both historical constructivist and suprematist works and of the work of certain so-so contemporary artists, their use as de-hierarchized reproductions in the “notebook,” the instrumental coldness that this marks, reveals a certain consonance with the world at large. In fact, turning the “notebook” into a compendium of homogenized stand-ins for her paintings, unsentimentally inserting another layer of mediation, doubles as Hadid’s way of coyly pointing to the layer of factors, a kind of substrate of information usually left unregistered, the malware that is also the platform, that determine what is at stake in the invitation for her to go notebook-quaint. In refusing first of all to celebrate the hand––her “exceptional manual talent”––that the introductory essays so anxiously bring up over and over, coming to close to making her sound like an heir to the Shakers, Hadid turns this monograph into an allegory of stultified contemporary experience itself.

Others have written extensively about Hadid’s paintings, going soft-at-the-knees over axonometric distortion and anamorphic spatiality and things like this, so there is no need to say too much about them here, especially since what matters is the way they are presented and not what they may be about. Let’s say, relying on dusty parlance, that it’s a matter of form and not content. It’s a matter of structural intervention, of how the notebook is used and how all that it wishes to hide is revealed or undermined. Unlike Kallach, who showed up to play his role while knowing that entire operation was rigged, Hadid highlighted, obliquely and maybe even anamorphically (when approached from a certain angle), the fact that an entire matrix of mechanisms and interests was at play by refusing to assume her role as its had been blueprinted. Deep down we all know that there are always impinging “impure” forces at work in projects like this and in our contemporary experiences, but just as deep down we are willing to pretend that they run no interference on the possibility of authenticity, of unmediated communication, of transmission of profound feeling. We hold on to this fantasy, even as we constantly claim to be above it. We are fetishists through and through.

One cringes a little at having to side with the celebrity, but things are rather black and white. One architect played the game in violation of the rules, the other was played by the game. Through the brutal coldness of reproduction and instrumentalization, transparently deployed, Hadid pisses all over our warm and fuzzy illusions, our nostalgia for the analogue, and our bad faith. To her credit, she got her “notebook” and then some; she scripted the thing and its negation. By not giving us treasures from the deep recesses of her thinking, while of course doing this all along, she exhibited unbendable fidelity to who she is, the general architectural project she captains, the icy lines of thinking she navigates, and the arctically-inhuman age that she––like the rest of us––has been sentenced to and has vigorously helped sustain and perpetuate.