Jawbreaker: A Hard, Sweet Time-Capsule of Punk’s Troubled Adolescence

04.12.12

Time efficiently whittles down your favorite bands; putting on some NOFX never occurs to me anymore. But some things just stick with you. One of mine is the emo-core band Jawbreaker, who are gradually reissuing their influential original albums on Blackball Records. Their relatively brief career straddled two related, highly charged cultural transitions: the alt-rock gold rush set off by Nirvana’s Nevermind, and the evolution of “emo,” a word you yelled at punk bands who played fancy and sang about feelings, into a slick corporate genre full of burnished sentiments and hooks. But the same pressures that would tear the band apart also shaped a discography that still sounds fresh and urgent 20 years later, thanks to the palpable conflicts roiling within it. In Jawbreaker’s songs, the narrative of hardcore’s turbulent exodus into less dogmatic, more melodic pastures is compressed in white-hot bursts of conflict between fury and vulnerability, sincerity and jadedness, politics and introspection. It feels a lot like growing up.

I didn’t discover Jawbreaker until 1997, shortly after they disbanded. This seemingly regrettable timing turned out to be apt. At the time, indie rock was infiltrating the steady diet of punk and rap that fueled my high school years. Jawbreaker was a perfect gateway into more sensuous and cerebral realms, with their chugging barre chords and ringing leads, film dialogue samples and enigmatic lyrics. This was especially true of their glorious, exhausted swan song, Dear You. After touring with Nirvana, they had signed with major label DGC to make a clean-sounding pop-punk record with the same guy who recorded Green Day’s Dookie. (You might vaguely recall “Fireman,” a skeletal anthem that somehow sounds both nervous and anesthetized, briefly flitting through MTV’s 120 Minutes.) This run at the mainstream didn’t pay off for Jawbreaker like it did for their most successful peers, Sunny Day Real Estate. In fact, it backfired. It is now hard to fathom the Rite of Spring-level calamity Dear You caused among devoted punk fans.

Jawbreaker was castigated in Maximum Rocknroll for selling out, and tales of Dear You songs being snubbed on tour are legendary. To be fair, at least a couple members of the band really didn’t like each other anymore, and their road-weariness had been well-documented on the scathing “Tour Song” several years prior. Judging from the adverse reactions at the time, you would think it was an AOR record heavy on piano balladry—which bandleader Blake Schwarzenbach would in fact broach later, with Jets to Brazil. But the nail in Jawbreaker’s coffin still holds up as a vibrant, realized mature album. Songs such as the burly “Chemistry” and the scouring “Lurker II: Dark Son of Night” belie the notion that Jawbreaker had gone soft. Even better, the added sonic polish pays off in atmospheric classics such as “Accident Prone,” and the lyrics are stuffed with rather ingenious wordplay. Dear You’s reputation has caught up with its quality in the decades since, as pitched battles between a clearly divided underground and mainstream have come to seem abstract.

Dear You was the first Jawbreaker record I ever heard. Coming into their discography from its poppiest end, I had none of the compunctions of punk partisans, and quickly moved backwards to fan favorite 24 Hour Revenge Therapy. It revealed a different but equally compelling band, more sludgy and spectral; more working-class-intellectual in affect. But the accessibility that would flower on Dear You shone clearly in songs such as “Ache” and the pop-punk classic “Box Car,” with its definitive refrain of “1-2-3-4 / Who’s punk, what’s the score?” 24 Hour Revenge Therapy and its predecessor, Bivouac, represent the intriguing developmental period when Jawbreaker explored something volatile between the punk of their debut and the pop-punk of their finale, harnessing ambitious sonic impulses to increasingly tuneful songcraft. Blackball Records’ reissue of Bivouac, due out on December 11, vividly whisks me back to that time when punk music and my own perspective were concurrently opening out into subtler colors of emotion; more nuanced and ironic perspectives.

After their cramped, sweaty, furious New York debut, which I wrote about at length when it was reissued, Jawbreaker moved to the Mission District to record this spacious, regal, furious follow-up. Having largely dispensed with ”the issues” on the preachy Unfun—a prickly bid to secure punk bona fides while spitting in the eye of punk purism—Jawbreaker got more personal and coded on Bivouac. The record opens with “Shield Your Eyes,” the first song that Schwarzenbach ever wrote and sang for Jawbreaker, when the band was still called Rise. Here, it takes on the character of a palate cleanser. A mist of low feedback clears to reveal a majestic landscape of rolling guitars and galloping drums, and the measured breadth feels like a repudiation of Unfun’s hysterical concentration. The invitation to “shield your eyes / stare at the sidewalk lines” is quite a change of pace from the prior insistence on inspecting hard truths. The band stretches out even farther on “Big,” giving the guitars acres of loping percussion to stroke, smatter and smear. “Don’t it make you feel small?” Schwarzenbach sings, apropos of the more human scale of his lyrics as well as the rangy, towering music.

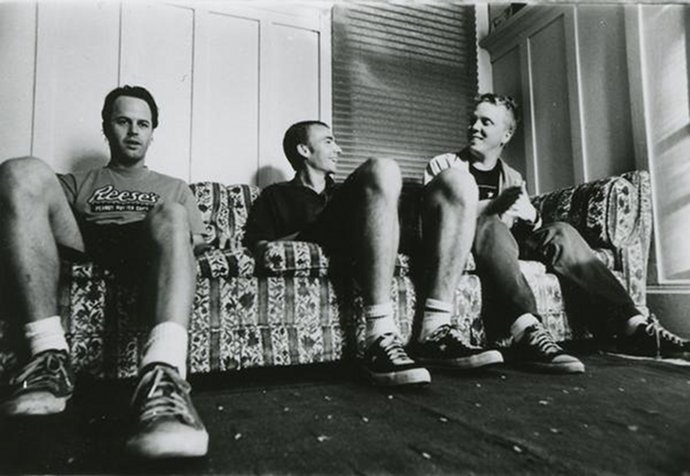

Unconstrained by the relentless forward momentum of hardcore, Bivouac explodes in every direction. Punk riffs are broken into elaborate sections with different time signatures, rippling with syncopations and contrasting timbres. The musicianship is styled with a sloppy energy, but makes no attempt to mask its practiced precision. The decompressed songs are powerfully motored by the tight, tumbling rhythm section of bassist Chris Bauermeister and drummer Adam Pfahler. Specializing in limber melodic counterpoint and daredevil fills, they provide an unshakable framework in which the guitars can morph freely from classic rock phrasing to pummeling hardcore, plangent arpeggios to slashing blues licks. Schwarzenbach’s voice sounds shredded, owing to throat polyps that necessitated surgery shortly afterward, increasing the impression of a man desperate to be heard at any cost. Angular art-punk nightmares such as “Parabola” and “Face Down” maintain a defiant edge, but elsewhere, more gradual catharsis emerges via roomy breakdowns, where the band stops combusting and starts to chug together as one, scrambling up long shallow slopes toward the horizon.

“Parabola” remains one of the strangest songs Jawbreaker every made, with thrumming bass and whistling feedback and distorted vocals wrangled into something that scandalously flirts with a dance music. But Bivouac also contains one of the band’s most beloved and approachable efforts, the punk rock comfort food of “Chesterfield King,” presiding over the more clangorous and/or mournfully beautiful excursions like a lodestar. A band that maintained such intense extremes was destined to be riven apart by the cultural convulsions it tried to navigate with integrity, at a time when the very meaning of the word was hotly contested in punk circles. This new document of Bivouac, with a boosted low-end and two excellent bonus tracks from the original sessions, reminds us of why this music outlasts the context of its time and the heyday of its brand: the timeless combination of skillful musicianship and a committed original vision.

__________

The 20th Anniversary reissue of Bivouac is available from Blackball Records on December 11th or for preorder.