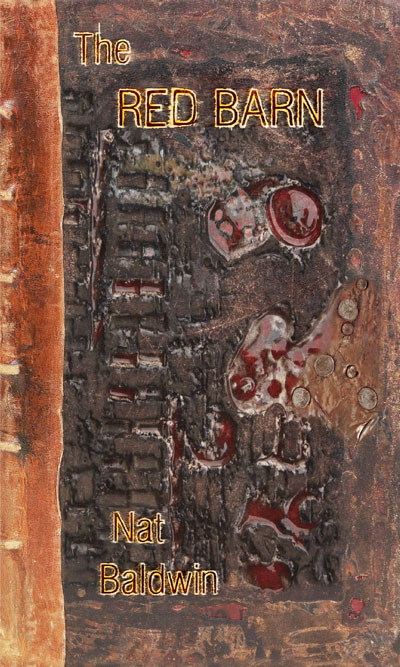

In The Red Barn: A Conversation with Nat Baldwin

11.04.17

Nat Baldwin has a few solo albums under his belt, plays bass in Dirty Projectors, and I hear he’s a pretty damn good basketball player, too. But he’s also a voracious reader of foreign and independent literature—has been for some time—and a magician with words himself, as his debut fiction collection demonstrates. The Red Barn is the rarest of rarities. The way Baldwin strings together words is no small feat. The sentences become trancelike, with reverberations and echoes of each other, though never in a redundant manner, and the whole becomes something akin to a Music for Airports in book form, though much more brutal and visceral in subject matter. It is a book of short sentences that smash into each other and then rebuild themselves anew, like I imagine how cancer cells duplicate in unknowing flesh and spread around to other organs.

Recently I had an opportunity to catch up with Nat and talk about his work.

TJW: The first story in The Red Barn, “A Crack in the Back of the Barn,” is essentially a matter-of-fact telling of the slaughter of an animal. We don’t even know what kind of animal just that it has hooves and nipples, the nipples are scraped off, as is the skin. It is pretty brutal. Have you ever seen Gaspar Noe’s film Carne?

TJW: The first story in The Red Barn, “A Crack in the Back of the Barn,” is essentially a matter-of-fact telling of the slaughter of an animal. We don’t even know what kind of animal just that it has hooves and nipples, the nipples are scraped off, as is the skin. It is pretty brutal. Have you ever seen Gaspar Noe’s film Carne?

Nat Baldwin: I haven’t seen Carne but just googled it and like the way it looks. I’m glad you felt the brutality of that story

Essentially Noe just went to a horse butcher and filmed the entire process of butchering a horse, up until the meat ends up on a plate. The brutality of your story has a kind of electricity to it, provided by the voyeurism of the person watching somebody watching and relating it all. What was there for you in the butchering of an animal in all of its gory detail?

I think that narrator is seeing something they’re not supposed to see, but something they see often, to the point where the way they tell the story makes it sound like something they do, although it’s really something they only do in their minds, or through the seeing, if that makes sense. They have other tasks around the barn, and a lot of the language (at least in a few of the others that connect with this first one) is supposed to be filtered through a mind that is receiving commands, though it’s unclear if the commands are coming from other people (i.e., those butchering the animal) or if the commands are simply the way the narrator organizes their own thoughts (i.e., obsessively commanding oneself to do certain things, behave certain ways, &c). Does that make sense?

I think so.

I guess I’m just curious how someone would think if they saw things like this on a regular basis; or, if they imagined things like this on a regular basis. Also, I think I want to draw attention to the fact that extreme violence is everywhere, if we stop and take a closer look.

I thought it was really effective in that it draws you into the brutality, making you complicit because you refuse to turn away.

I love a fiction that creates total immersion, whether it’s through the world-building or simply through language or the tension between both.

I think you definitely do that in this collection. Which kind of takes us into the second story, “Rabbits out Back in the Burn Pile.”

That one was fun to write! I think I wrote a lot of it while on my back porch (in a house I don’t live in anymore) looking into the void of the forest. I read some police reports in order to compose that piece.

It is inspired by some sort of true crime?

That one is. I abstract it quite a bit, of course, but I became very intrigued by the story of some murders that happened on a farm not too far from where I’m from. I actually was reading about it and then realized the murderer sort of reminded me of one of the narrators in “This Noise Does Not Stop” and thought they could create a kind of conversation.

I like the idea that the first story is about an animal being slaughtered in a barn, hung up and cut and de-skinned and all that, and then in the next story, we get a barn, a man in it, in a chair, drooling, not talking, with cuts all over him, and at one point we are told there are no animals anywhere, even though I kept getting this feeling that the man was an animal, and then all the sudden, there is a dead body on the shore, and we have a person harnessing it up like an animal to drag it back home, to the barn, where it is hoisted up in the same position as the animal slaughtered in the first story. Were you aware of that juxtaposition while you were writing these two separate stories?

I wasn’t totally aware, although I guess I’m aware that I like the idea of people/animals hanging—”like” doesn’t totally make sense, of course. I just mean in a fictional sense, as a way to explore extreme territory.

The way the light hits the suspended corpse at the end of “Rabbits” kind of made the story take on a biblical feel, at least to me.

“This Noise Does Not Stop” was one of the first in the collection that I wrote. I thought while I was writing it that it could be a novel, or something that lasts a bit longer. But then it needed to stop. There are multiple narrators in that one, so I found a way (or they found their way) to creep into the other stories.

Do you put much importance into understanding a text? I don’t. The experience is where it’s at for me.

I’m totally with you on receiving the text as an experience, as opposed to understanding each line or plot move. I think that’s one of the amazing things about language that is truly difficult to articulate, the way feelings emerge from things that challenge conventional notions of sense-making.

But it’s the same thing with music or visual art too, right? Like when I listen to Wolf Eyes I’m not considering if it makes sense to me or not, I’m experiencing the sounds.

I wanted to ask about “The Shape of a Face.” That’s one of my favorite stories in the collection. Also, it’s one of the shortest. And for some reason, I felt, maybe one of the most symbolic, if symbols are even utilized. Where did that story come from? Also, the last two lines, loved how they were about the same length, mirrored each other, and mocked each other in their rhyme.

I’m glad you like that one! That definitely came from a specific prompt from Peter Markus. The sestina exercise–I chose six words and just repeated them as much as possible. Sestina is that poetic form that has six lines to a stanza, with the same words ending each line (although moved around in a specific way from stanza to stanza). I think I’m not doing a great job at describing it.

I think we just read a few works that fit that form and just had to keep that in mind while composing the story, although we didn’t have to follow as strict a structure as an actual sestina.

Are you familiar with Gordon Lish’s idea of consecution? Like repeating words form sentence to sentence, propelling sentences into the next sentence and so on and on and on forever, like it builds momentum. Did Peter make you listen to that Cat Power song “Names” and then write about people you know, changing their names, and fictionalizing their lives, etc.?

I guess just sort of peripherally, re: Lish, and also just absorbing vis a vis so many of his students or people he edited. Yes about Cat Power, too! “Names” is really, really good. Early Cat Power totally rules.

What’s the Cat Power album Steve Shelley played drums on, her first one? Myra Lee?

What’s the Cat Power album Steve Shelley played drums on, her first one? Myra Lee?

I thought Jim White plays on it — maybe I’m thinking of Moon Pix? Wait, I might not know Myra Lee.

Yeah, it’s her first one, not very well-known, but one of my favorite records ever. I really like how Peter uses music to prompt people to write fiction. I also liked how he would print your story out, mark it up with pen, and then scan the pages back to you. One of the best teachers I have ever had.

I guess I sort of started with Moon Pix, which I realize now is like starting with Either/Or and skipping Roman Candle and the self-titled one, and I agree, definitely one of the best teachers I’ve ever had.

Myra Lee was the first cat power album I heard because I bought it used at CD Trade Post here in Wichita, when I was like 16. So everything else was measured by that record. Also, I’m a Sonic Youth geek and I saw Steve Shelley played drums on it. Dark as fuck, the whole album is. I think I read somewhere that Myra Lee was Chan’s mother’s name.

I wish I knew who Cat Power was when I was 16, or Sonic Youth. I guess my taste in jazz was pretty sophisticated back then, but I had no idea about all the awesome indie stuff that was happening.

You know what’s weird? My dad is like this amazing jazz guitarist, I grew up with jazz, and I think I started bucking it in my teens, but I love it now, the appreciation has been restored. Don’t you have a tattoo of the cover of Machine Gun?

You know what’s weird? My dad is like this amazing jazz guitarist, I grew up with jazz, and I think I started bucking it in my teens, but I love it now, the appreciation has been restored. Don’t you have a tattoo of the cover of Machine Gun?

Yes! It is a fucked up tattoo to have. I have a complicated relationship with it. Definitely difficult to describe to people when the actual image itself is just two army dudes with a machine gun; and on the other hand, people that know the album probably think it’s like too iconic of an album to inscribe in your skin. I hate guns and hate the US military’s involvement in destroying the world and I hate the militarization of our police force here at home. I have to remind myself that the gun is a metaphor, destroying all hierarchies and everything the military (and all systemic violence) is fighting to uphold.

——————–

The Red Barn is available now from Calamari Press.