In the Garble: A Review of Alice Notley’s Negativity’s Kiss

18.02.16

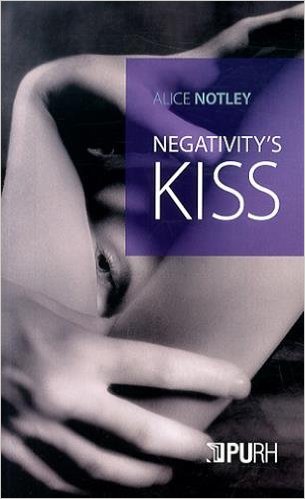

Negativitiy’s Kiss

Negativitiy’s Kiss

by Alice Notley

Presses universitaires de Rouen et du Havre

200 pp. / $22.00

Above my desk is a photocopy of a watercolor by Alice Notley: a bottle next to a near-empty wine glass, a spool of thread, and below these objects the question, in lithe cursive, “You ask him, what would be the point?” The painting refuses story as much as it suggests a narrative presence, offering a negative definition of action that turns plot into occasional, almost humorous color, a warm stain of movement. Everything about it is thickly elemental, barely there. If it is a still-life, the stillness in it is totally activated. The arrangement and language of the work, shaped in the face of resignation although rebuffing any acquiescence, generate an attractive power. A voice emerges there, elegantly and defiantly refusing. It’s not always going to be charming.

The same voice resonates in Notley’s book-length noir poem Negativity’s Kiss, a work that like her watercolor is saturated with spirit, revulsion, and vision. Following the voice of Inessential “Ines” Geronimo, a poet recently shot in a seedy, ambiguous city and surrounded by possible assailants and saints, the book imagines a brutal, satirical world where all language and communication, including the answer to who shot Ines, are mired in the Garble, an internet-like substance that obscures truth, although the poems of Ines intermittently leak out. Notley animates characters such as Copernicus “Cop” Smith, the detective investigating Ines’s shooting, Current Sweetheart, a jealous up-and-coming poet-darling of the mainstream, and Charlatan Gregory, the CEO of a multimedia conglomerate aimed to destroy Ines’s reputation. As John Ashbery once said about Gertrude Stein’s Stanzas in Meditation, Negativity’s Kiss is a “poem that is always threatening to become a novel,” and in this case, a genre novel. Adopting all the pulpy energy of the whodunit crime novel while abandoning the sluggish prose that packages it, the poem disregards dialogue for a fluidity of voices, trades plot for a complexity of textures and motives, and, like all of Notley’s work, generates a music that breaks the song.

That Negativity’s Kiss embraces pulp genres shouldn’t come as a surprise, and it certainly doesn’t make this book an outlier from Notley’s other recent work. Books like Benediction and Disobedience rail against any orthodoxy of form or genre, including the vocabularies tied to those distinctions, and readers of Notley’s earlier works will recognize the vitality and humor she sources from mass entertainment, from Academy Awards ceremonies to professional boxing to Sesame Street. Bob Dylan, whose songs have been essential for Notley as well as for her first husband Ted Berrigan, also influences this book, as the opening lyrics of “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”: “When you’re lost in the rain in Juarez / And it’s Eastertime too / And your gravity fails / And negativity don’t pull you through,” serve as the origin for the book’s title.

The renewal of sources like folk lyrics, comics, and genre fiction have been valuable to many of Notley’s New York School-era peers, evidenced by Berrigan’s little-known western novel Clear the Range (1977), made by crossing out and rearranging the text of a pulp cowboy novel, Lorenzo Thomas’s Dracula (1973), a poem that confronts the racist imaginary of the oft-repeated Eurocentric horror story from the perspective of the mid-1960s, and Ed Dorn’s epic Gunslinger. Jack Spicer’s posthumously published detective novel, The Tower of Babel (1994), a terrific send-up of the mid-1950s poetry community in San Francisco, links directly to Negativity’s Kiss, especially in both books’ satirical, uncompromising perspectives on the deadness of certain aesthetics, or aesthetics in general. There’s also a poets theater quality to the arrangement of voices in Negativity’s Kiss, like a hardboiled Kenward Elmslie. None of these examples are precedents for Notley’s noir poem. Rather, they show a lineage of participation with uncommon sources. It seems one of the book’s goals, if only tacitly, is to insist that if such sources don’t constitute literature, then no one needs it. Literature is all Garble anyway, at least in Negativity’s Kiss.

As Notley writes in “Poem” from Incidentals in the Day World (1973), “I weep I read novels,” and this activated despair is far different than W.H. Auden’s relationship to pulp prose in his very literary essay “The Guilty Vicarage: Notes on the Detective Story, by an Addict.” Though Notley and Auden share a lifelong devotion to the detective novel, Auden’s moralistic description of the genre’s supposed classic unities is a gendered departure from Notley’s poetic activation of the form’s critical capacity. As a noir poem, Negativity’s Kiss is part of a larger insistence on amplifying through the Garble, on indicting the casual evil, as well as the casual dullness, of contemporary living and literature. “We live in a prose culture, a film culture, a media culture,” said Notley at a recent event at The Graduate Center at CUNY, “I think we should live in a poetry culture. Steal everything back from everywhere and put it back in poetry. That is my ambition.”

Beyond the genre trappings that Notley steals back for Negativity’s Kiss, it also steals back the ability and necessity of poetry to dismantle itself and its own assumptions. That Ines is inessential is what gives her the capacity to resist the homogenization of the Garble, the desire of the Street (its own animate character) to level her, and Verball, one of the possible killers, from owning her. But poets and poetry do not fair well in Negativity’s Kiss, whether due to careerism, vanity, or violent suppression, and as ecological devastation looms at the end of the book it seems unlikely that poetry will save anything. What to say in the face of this doom? “I Ines say, go to hell you vicious motherfuckers” is one possibility. If there is intimacy at the end of the world, Notley’s work promises it, and devastatingly so.