In Search of Duende: Fiona Apple and the Endless Container

17.04.18

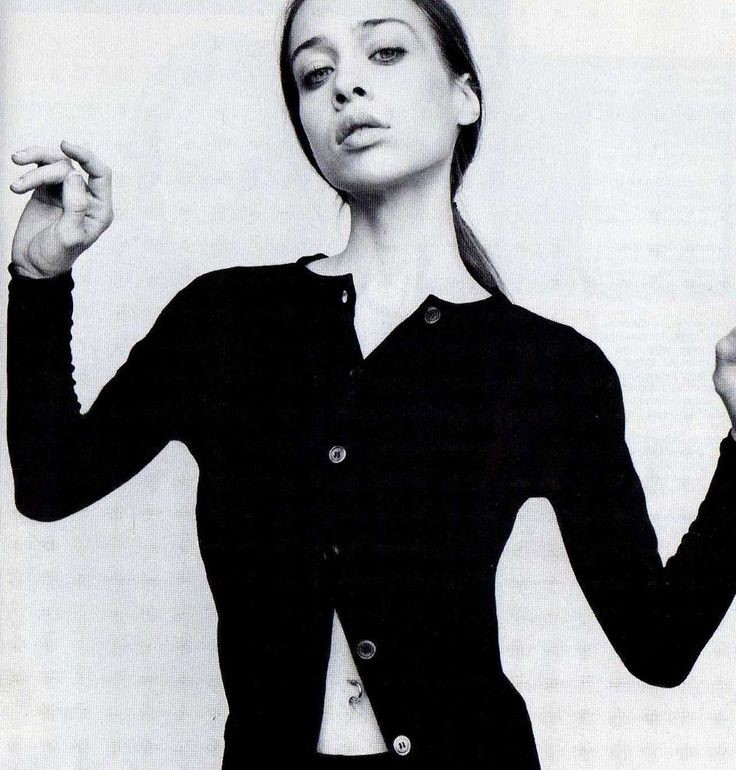

Fiona Apple once claimed that her work on Tidal was not the result of a highly publicized traumatic event she suffered earlier in life. “It doesn’t get into the writing,” she told Q magazine in 2000, about having been raped when she was just twelve. Apple was only responding to an inevitable question about the lyrics to “Sullen Girl,” which were included in nearly every review of her 1996 debut, released when she was eighteen.

Is that why they call me a sullen girl, sullen girl

They don’t know I used to sail the deep and tranquil sea

But he washed me ‘shore

And he took my pearl

And left an empty shell of me

You can’t really blame her for wanting to distance her work from her trauma. A 1997 arts feature on Apple in the New York Times carried the headline, “A Message Far Less Pretty Than the Face.” It’s hard to imagine what it must have been like to be open about her rape in the nineties, especially having catapulted to fame so young. On her way home from school one day, a man had caught the door behind her as she was entering her mother’s Manhattan apartment building. He cornered her in the corridor with a weapon, and said if she screamed he’d kill her.

In 1998, she told Rolling Stone that she didn’t think she would have achieved the same success if what happened to her had never occurred. She may have been right, but not due to any lack of talent. Posttraumatic growth is known to open doors that otherwise would never appear—and to deepen an individual’s ability to forge emotional connections. Tidal certainly resonated with an entire generation of young women who, like me, had no idea how to manage their own internal seas. Apple offered a safe place for us to store the unruliest of our emotions—sadness, anger, and jealousy.

And there’s too much going on

But it’s calm under the waves

In the blue of my oblivion

Under the waves

In the blue of my oblivion

***

Billie Holiday, one of Apple’s influences, was also raped—by a middle-aged neighbor in an abandoned house when she was just ten, for which she was imprisoned and later sent to reform school. She eventually turned to prostitution, alcohol, and heroin. In reference to her career, and specifically the song “Lady Sings the Blues,” Maggie Nelson wrote, “To see blue in deeper and deeper saturation is eventually to move toward darkness.”

Holiday and Apple can both be said to possess duende, a concept that is notoriously difficult to define, beyond the fact that it originates in Spain and describes an artistic soulfulness—often linked to darkness—which cannot be faked through any level of mastery or performance. In “Theory and Play of the Duende,” a seminal work on the subject, the early 20th century poet, playwright, and director Federico García Lorca writes, “The great artists of Southern Spain, Gypsy or flamenco, singers, dancers, musicians, know that emotion is impossible without the arrival of the duende.”

In his essay, Lorca suggests that duende is not drawn from external forces such as style, but rises from inside of the artist—the blood itself. “The duende wounds,” he explains, and “in trying to heal that wound that never heals, lies the strangeness, the inventiveness of a man’s work.” Apple’s songs, as she once suggested, may not directly reference the past, but that doesn’t mean the two aren’t linked.

Some trauma theorists believe that the memory is not only etched in the mind, but also stored in the body. The cause of trauma is universally recognized as having witnessed or experienced events that involve the threat of death or serious bodily injury. This is where trauma and duende share a striking similarity: Lorca believed it would only appear if the artist has come face-to-face with the possibility of death.

He points out that in Spain, one needs look no further than the bullfight to understand death as a national spectacle—a performance. “At the moment of the kill, the aid of the duende is required to drive home the nail of artistic truth.” We replicate a similar thrill by consuming art derived from trauma; by experiencing another’s suffering from a safe distance. As Lorca suggests, “Neither in Spanish dance nor in the bullfight does anyone enjoy himself: the duende charges itself with creating suffering by means of a drama of living forms, and clears the way for an escape from the reality that surrounds us.”

The escape vessel produced by Apple’s Tidal is twofold: the audience both has the opportunity to engage in what Carl Jung called participation mystique—sharing an identity and symbolic life with something outside of one’s self—as well as a bit of healthy projection. We simultaneously participate in Apple’s pain while using her performance as a container for our own. That way, we too get the chance to bleed.

***

“The duende never repeats itself, any more than the waves of the sea do in a storm,” writes Lorca. An artist doesn’t lose her soulfulness over time—she just finds new ways to express it. In the 1997 feature, “A Message Far Less Pretty Than the Face,” Apple stated, post-Tidal, “I’ve already written new stuff and I have to let it out.”

She seemed to be speaking to the struggle that duende is said to delight in with its creator, as if it were banging on a cage, begging to be let out. Or maybe it’s the other way around—the creator summoning her pain, in an attempt to expunge it. Either way, the fire continues to burn, and Apple is the kindling. In Bluets, Nelson once called the blue flame at the core of a fire “an excellent example of how blue gives way to darkness—and then how, without warning, the darkness grows up into a cone of light.”

This is perhaps the best metaphor I’ve found for duende. The artist digs deep into her sadness to wrestle with its cause, which then surprises her with a kind of beauty—a light that could not be born of anything else. In keeping with the Spanish belief that death is merely another beginning, out of the ashes comes, as Lorca put it, “an endless baptism of freshly created things.”

Apple has released three albums since her debut, in between hiatuses, and to varying degrees of critical acclaim and commercial success. And though her writing has become more pointed and her style more refined, none has pierced me in quite the same way as Tidal. Perhaps this is because, in the late nineties, I was also a sad teenager who had experienced trauma. Her album was the first place my emotions felt acceptable, marking the beginning of what would become my own struggle with an indefinable force that seemed to be devouring me from the inside.

Twenty years later, I was quick to purchase Tidal upon its release on vinyl. When I listen to the record now, I do so not while driving a car with the sunroof open, the wind in my hair, a joint in-hand—but on a leather couch, snuggled in a blanket, a few drops of CBD tincture under my tongue. As I fall into the blue of Apple’s oblivion, time seems to suspend itself. I notice my feelings are no longer linked to any particular set of events. I can’t be sure how much of the emotional intensity belongs to Apple, and how much belongs to me—only that I never want the entwinement to end.