In Search of Duende: Diane Arbus at the Met

06.09.16

On a Friday afternoon in August, I go to an exhibition of Diane Arbus with my notebook. On my mind is duende: that sometimes wicked, sometimes ugly, often mischievous third force in art that Lorca writes about in his essay Theory and Play of the Duende. The first force is the angel, Lorca says. The angel guides, grants, proclaims, forewarns, and dazzles. The second force is the muse, which dictates, prompts, and stirs the intellect. The third “mysterious force that everyone feels and no philosopher has explained” is duende. Duende “shatters styles…, strips [you] stark naked in the cold of the Pyrenees, …or gives [you] the eyes of a dead fish, at dawn, on the boulevard.”

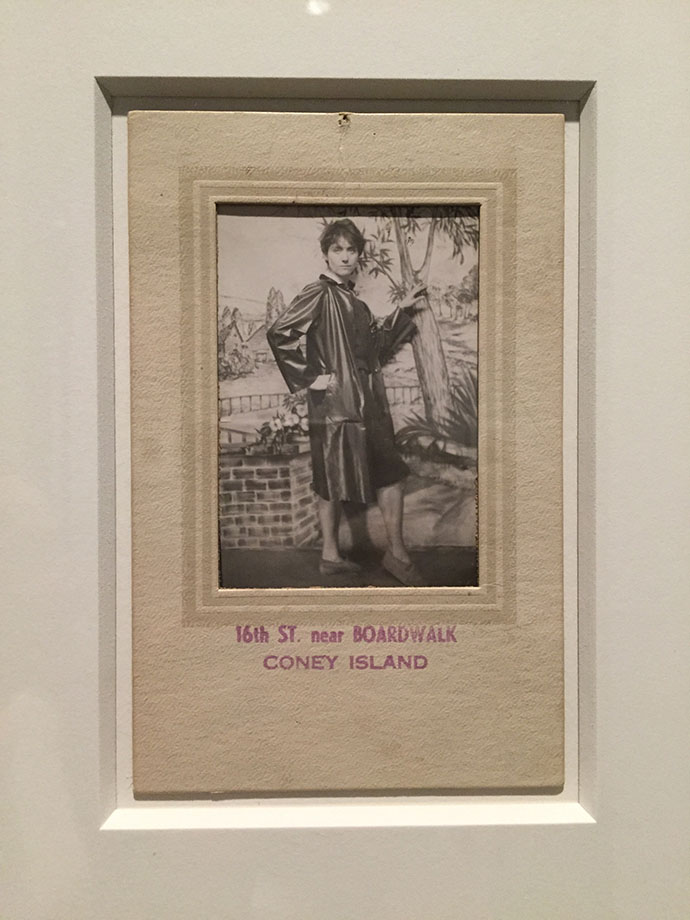

Each photograph is lit individually on its own narrow wall. It covers Arbus’s early years, 1956-1962. She was 33 when she broke off from the photography business she had started with her husband and began lying in wait for unsuspecting subjects in doorways, like a predator, alone. Despite the way it helped her develop her fearlessness, street photography would not end up being an approach particularly well-suited to her style, in the end. Street photography is about seizing fleeting moments. It is psychologically arresting only by accident.

Arbus’s best work was created not spontaneously but over the course of time. She sat with her subjects and antagonized them for hours—sometimes fucked them—to get the shot she wanted. In these early photos her powers are still inconsistent. She has not yet learned to strip naked, as she famously did in the nudist colony, and hold her camera between her breasts to shoot that naked aging couple frankly. She has not yet become completely and irrevocably herself.

And yet she is already drawn to the most pure, warped, and complex facial expressions. If as works of art these photographs’ own duende is inconsistent, nearly all of them document a certain duende in their subjects’ expressions. I start a list of what I find in these strangers’ faces: confrontation, supplication, fury, embarrassment, defensiveness. Obedience, fear, judgment, rapture, concern, bliss, boredom. Denial, argument, sass, sex, nervousness, contentment. Confidence, curiosity, expectation, skepticism. Exhaustion, arrogance, charm. Mugging, madness, over it, fuck off. Duende.

Just when I think I’ve got it, Lorca interrupts me to confuse the issue.

I don’t want anyone to confuse the duende with the theological demon of doubt at whom Luther, with Bacchic feeling, hurled a pot of ink in Eisenach, nor the Catholic devil, destructive and of low intelligence, who disguised himself as a bitch to enter convents, nor the talking monkey carried by Cervantes’ Malgesi in his comedy of jealousies in the Andalusian woods.

There is something of the bitch, something of the talking monkey, in Arbus’s work. Am I confusing duende with the demonic?

The word duende originally referred to a sort of house-haunting goblin. It is derived from a contraction of the phrase dueño de casa or duen de casa—literally, “possessor of a house.” There is certainly something of the goblin in these images. I begin to resent Lorca for is obliqueness. It seems to me he’s attempted to channel duende without actually defining it.

He doesn’t notice my annoyance, of course. He just goes on:

The hut, the wheel of a cart, the razor, and the prickly beards of shepherds, the barren moon, the flies, the damp cupboards, the rubble, the lace-covered saints, the wounding lines of eaves and balconies, in Spain grow tiny weeds of death, allusions and voices, perceptible to an alert spirit, that fill the memory with the stale air of our own passing.

One might add to this list: a lampshade kept in its plastic wrapping, a Christmas tree in a low room dripping with flaccid tinsel, a little jar containing the dual fetus of Siamese twins.

I can feel Arbus tugging at the darkness, both figurative and literal. Yet I can also see her emphasizing the literal darkness artificially, during the printing process. By overexposing the prints. By overemphasizing the lightness of hands, the brilliance of outlines. She is lascivious but that is not what makes her good. The siamese twin fetus in the jar by a carnival tent is not shocking so much as it is lonely. It seems to have been abandoned. It sits in the dark with its strange, unborn stillness, waiting.

I imagine an exchange between Arbus and Lorca, in their own words.

Lorca: The arrival of the duende presupposes a radical change to all the old kinds of form, brings totally unknown and fresh sensations.

Arbus: Nothing is ever the same as they say it was.

Lorca: The duende never repeats itself, any more than the waves of the sea do in a storm.

Arbus: It’s what I’ve never seen before that I recognize.

Lorca: The duende loves the edge, the wound, and draws close to places where forms fuse in a yearning beyond visible expression.

Arbus: A photograph is a secret about a secret.

Lorca: The duende… won’t appear if he can’t see the possibility of death, if he doesn’t know he can haunt death’s house…. With idea, sound, gesture, the duende delights in struggling freely with the creator on the edge of the pit. Angel and Muse flee, with violin and compasses, and the duende wounds, and in trying to heal that wound that never heals, lies the strangeness, the inventiveness of a man’s work.

Arbus: The condition of photographing is maybe the condition of being on the brink of conversion to anything.

Lorca: In every other country death is an ending. It appears and they close the curtains. Not in Spain. In Spain they open them. Many Spaniards live indoors till the day they die and are carried into the sun. A dead man in Spain is more alive when dead than anywhere else on earth: his profile cuts like the edge of a barber’s razor.

Lorca always has to have the last word.

But of course words are his medium. Arbus works in the medium of light. In one photograph, I find a hospital room. White walls white bed white sheets all bright with light. An old white woman is dying in the bed. Her mouth is open. It is the beak of a dozing turtle. I recognize that face—the face of an old person near death. It is the face of my maternal grandmother.

On the other side of the room is a corpse with a receding hairline and a toe tag. His ribcage has been cracked open, his skin split, to reveal the wet dark of his insides. One hand lies over the split, near where his belly button would have been, in a gesture of casual repose. The elderly, well-dressed woman peering at the photograph beside me says: “Is his body… open?” I point to the word corpse on the wall label. She says: “Well, I know. But is it… open?”

And I look up and around to find that my fellow museum visitors have all become Diane Arbus characters themselves. They gawk into the photographs, intrigued. They laugh uncomfortably as if they’re in on the joke, but aren’t sure they like it. They gape, repulsed, or lean in, fascinated, or look away too suddenly. The duende here is not so much in the photographs themselves as it is in us, the viewers.