IDEAL HOME NOISE #12: Robert Frank

15.05.17

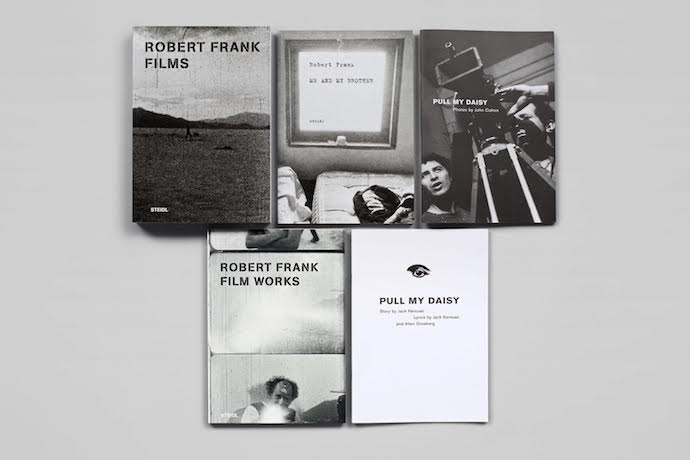

This column normally highlights three different items, but the focus here is on a single offering: Robert Frank Film Works (Steidl). This sprawling 8-DVD box set is housed in a wooden box and collects 27 movies by the artist Jim Jarmusch and Richard Linklater consider the godfather of American independent cinema. Out of circulation for decades, these films are presented in carefully restored versions along with four books that catalog this important and widely misunderstood work.

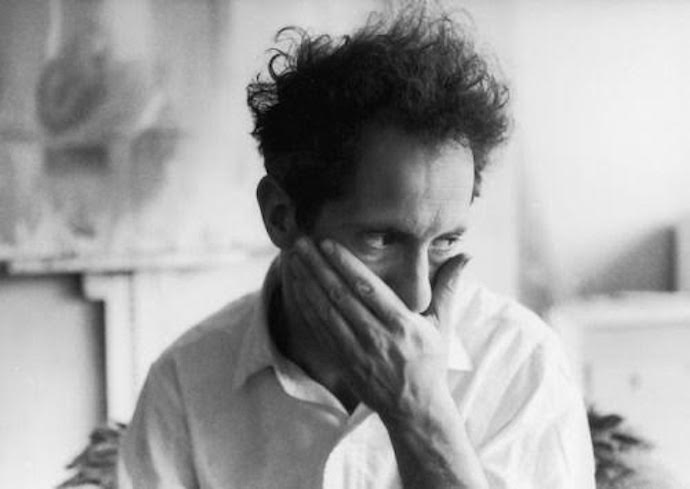

ROBERT FRANK

Robert Frank is best known for his now classic 1958 photography book The Americans, whose raw and indelible shots taken during a road trip across the country shifted the aesthetics of an entire medium. The book made Frank a minor celebrity but rather than capitalize on his success, he swerved into filmmaking. Over the next 50 years, he made 30 films. They’re all included in Film Works except for the infamous and still banned Rolling Stones tour documentary Cocksucker Blues, the surprisingly conventional feature Candy Mountain, and a Patti Smith music video.

Frank’s films are no less radical than his photography. But where critics eventually acknowledged the importance of The Americans, his movies have been largely scorned when they weren’t ignored altogether. By dedicating himself to film, he effectively vanished into obscurity. The New York Times titled a 1994 profile “Where Have You Gone, Robert Frank?”

Complex and often contradictory, the films resist easy categories. They mix documentary methods and fictional narratives, stylized performance techniques found in experimental theater and the amateur intimacies of home movies. Uninterested in classically framed shots and dramatic crescendos, his ragged movies instead offer immediacy and a sort of anti-beauty. They may initially appear to have been casually edited with a chainsaw, but repeated viewings reveal their intricate construction and rich emotional connections.

DAISIES AND DEAD ENDS

Frank’s first film remains his most famous. Co-directed with painter Alfred Lesley, the 30-minute short Pull My Daisy (1959) is a key document of the Beat Generation, featuring Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and Peter Orlovsky at an awkward party in a New York City loft. It blends improvisation and documentary footage with a poetic and playful voiceover by Jack Kerouac. Debuting on a double-bill with John Cassavetes’ Shadows, it opened up new narrative possibilities for American cinema.

His next two short films were more conventional and less successful. The fabulist version of Isaac Babel’s story The Sin of Jesus (1961) mostly fell flat and the slick domestic ennui of O.K. End Here (1963) came off as faux Antonioni. O.K. End Here always struck me as aptly titled, a recognition that Frank had reached an aesthetic dead end. Sure enough, he would reinvent himself with his next film, an ambitious feature shot over four years.

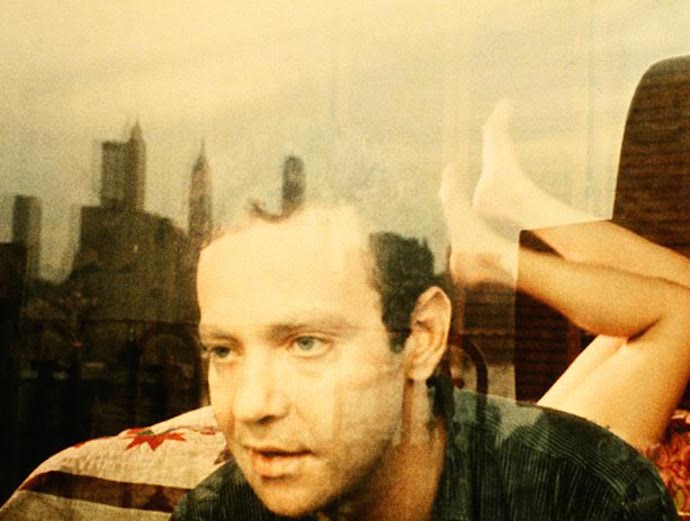

ME AND MY BROTHER

Me and My Brother (1968) is a major work that contains the seeds of Frank’s future films. It chronicles the relationship between poet Peter Orlovsky and his often catatonic brother Julius. The 90-minute film tries to capture moments of real life while aware of the near impossibility of achieving this. Its Mobius strip structure constantly folds in on itself, deploying and discarding strategies from showing straight documentary footage to restaging scenes from life to hiring an actor to replace Julius. It’s a dizzying, disorienting, and ultimately deeply moving film about the difficulty of representing a single moment of truth.

“The truth is somewhere between the documentary and the fictional, and that is what I try to show,” Frank said. “What is real one moment has become imaginary the next. You believe what you see now, and the next second you don’t anymore.”

RESTLESS CREATIONS AND NEW ROUTES

The exceptional films that follow Me and My Brother expand upon its many strategies. Conversations in Vermont (1969) switches between voiceover, interviews, and still images to create a family snapshot. Liferaft Earth (1969) starts as a documentary about a California “starve in” and ends as a hallucinatory essay film. About Me: A Musical (1971) uses an actor to portray Frank and includes scenes of Texas prisoners and Indian temple musicians. It both undermines and expands the concept of a self-portrait. Life Dances On (1980) pushes the free associative flow even further, moving between rehearsed fictions and raw confessions, all grounded in the loss of Frank’s daughter and the mental illness of his son.

The films mostly clock in around 30 minutes. This short format allowed Frank to collage together far-flung footage without the films becoming too diffuse. His movies never stay in one place for long, shuttling between moods and modes, often blurring the line between life and art, past and present. While they’re often melancholy, there’s also a sly humor that’s easy to overlook.

Even the purely fictional films Frank made in collaboration with novelist and screenwriter Rudy Wurlitzer, starring luminaries such as William S. Burroughs and sculptor Richard Serra, are filled with unexpected detours. Keep Busy (1975) and Energy and How to Get It (1981) offer weather reports recited like Beckett texts, musical interludes, fake documentary footage, and odd rituals. From moment to moment, you’re never sure what might come next.

DEEPER INTO VIDEO

With the diary film Home Improvements (1985), Frank embraced video. His later films force viewers to work harder to find the beauty in the ramshackle compositions. Video freed him to make experiments like One Hour (1990), a real-time trek through the streets of downtown New York that blends fiction and reality without a single edit. Last Supper (1992) affectingly intercuts video portraits of Harlem residents with a staged outdoor dinner party held in their neighborhood for a guest who never arrives.

Scenes from earlier films and images of his photographs often reappear in Frank’s films, putting them in conversation with one another. True Story (2004) is particularly aggressive in remixing and recontextualizing Frank’s previous work. It replays a revelatory scene from The Present (1996) where a painter arduously scratches the word “Memory” from a wall until all that remain are two letters: “Me.”

THE PACKAGING

The elaborately packaged Film Works also contains the script for Pull My Daisy, a book of John Cohen photos taken during that film’s production, and the screenplay for Me and My Brother. Best of all is Robert Frank Films, a handsome 300-page monograph filled with illuminating essays, interviews, and film stills. Unfortunately, the paper sleeve that holds the DVDs tends to badly scrape and scratch the discs. So you need to be extra careful. The publisher, Steidl, is offering refunds or replacement sets for anyone who encounters this problem.

END HERE

Throughout his career, Robert Frank has remained uncompromising in his approach to story and image. His work makes you aware of often art caters to our preconceptions and flatters our taste. His films are a potent reminder that while good art is always recognizable, great art rarely looks and acts like we think it should.