“From a reflection in both paintings”: Valerie Mejer’s Rain of the Future as the Fragments of Narrative

22.07.14

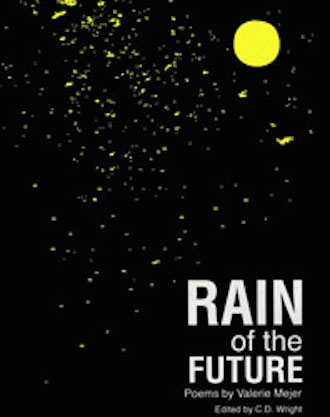

Rain of the Future

Rain of the Future

Valerie Mejer

Action Books

114 pp. / $12

Raúl Zurita introduces Valerie Mejer’s poetry with the following words: “only through radical vulnerability can the urgency of love arise.” He calls her work a series of photographs, allowing us to claim what we find in her verse as hemorrhage, weakeness even. Mejer, a Mexican poet with roots in Germany, Britain, and Spain, is a unique voice writing in a postmodern state where things don’t always seem so whole. She beautifully weaves a breakdown of narrative by carrying us through family stories, photographs of her loved ones, and love’s outcries and declarations.

The book is set up in four parts. The first, from the way, the way, begins as if on a journey. Mejer interrogates our animal bodies, the things that make failure inevitable (and beautiful) in a world where bad things happen, as we all know too well. She weaves a story of sleeping and waking, always perpetually coming out of a dream but then finding that this “aliveness” can’t quite last. Here’s a sample from the section’s title poem:

Waking up, we are swallowed in wakefulness.

The house swallows us in its terrible thirst. The routine of taking our children

to school swallows us

and so does the if only I could.

Here Mejer sets up a thread that recurs throughout the book, a story of what it means to be fearful while still wanting to engage in worlds of memory that are birthed by that first house that she continually comes back to. She writes of being “freed from a weight” in “Eye of Heaven”; also, of being “faithful to a world unknown, / a world for us alone, paper-thin, and too fragile to speak of.” These fragilities are echoed in characters that she paints, uncanny as that may seem: “Before that, that day, in a museum of mummies, we’d seen two French doctors, a Chinese woman, a drowned man and a woman whose hands, frozen above her face, seemed to be trying to push something upward…. Returning along the road, we glimpsed a pack of ostriches running behind a fence.”

Mejer’s characters are fragments of history, and it’s not just her history: it’s a collective history of who-might-have-been-hurting, bringing her readers back to that radical vulnerability that speaks of love so quietly. In another poem, she writes: “We came to the beach: the sand sewn by ashy light…. Asleep, we know so much.” She gives so much to this sleeping and rising theme that we know for sure as readers there’s a “wakeful” mystery that can’t quite be touched but can only be hinted at.

In section two, Ashes of a Map, Mejer employs fragments to show what happens when narrative breaks apart: she writes succinctly, in paragraphs, and with attention to details of the past. Again, we have the same theme of sleeping, waking, and living through the vulnerable tension between these two states: “Little Havana, stern girl, float back chameleon-like towards the black tree: until you wake, until we waken.” Mejer uses places as incarnations of people, and vice versa. We get the sense that she is steeped in the geography of her heritage, and that her poetry is based in a deep historical longing for wholeness past the brokenness of sleep. In a lovely untitled poem, she writes:

Let’s say that the eye is a country,

and that the ear

and the mouth and the skin are a country.

…

Since then, we’ve palmed

and bitten a soft fruit

salty as blood.

Here we have the architecture of place embodied, something that Mejer’s poetry is so good at. In “Ode to Stay,” she writes: “The sun’s light touches you, touches us…. And the river will be the vein of a body, the aorta of a victorious old woman, Our Lady of Paris.” She creates mythological places that are real places, too, embodying associations her readers might have with what we see of these places—either through our travels or by proxy, by reading or looking at images, etc. She even makes a jungle live: “He is, like dogs, patient with children and lets us climb to his peak, lets us recount his steps, invent his supposed life as a carnivorous animal, his painstaking relationship with a hungry goddess…. He doesn’t sweat as we do in Veracruz, he fathoms.”

We get the sense that this jungle is a person, a creature, and the line between human and animal is blurred sufficiently. This seriousness of affect is part of the semi-religious tone that drives the book, and it’s a necessary and beautiful sentiment.

In the book’s third section, this vulnerability is extended through “On the Third Day”; Mejer writes of kisses that “kill us,” and this serious take on the way a world can be closed is presented again in the book’s last section, “Rain of the Future.” It’s raining; that much is clear. There’s an intense longing to be loved here, as in the section’s first poem:

We fully embrace the mirage.

The books simultaneously speak:

Their murmur is the truth.

It has rained enough

for us to be clean and peaceful.

A memory invades,

memory of skates and of order.

I am so beautiful and they don’t know it.

Who is the they that Mejer writes of? Perhaps it is those who have hurt her, or those by whom she has been partly made as a subject of the world. This sense of pain is part of the book’s vulnerability, and in the next poem she writes of the sky being hollow, of “the atmosphere…our breast / caressed by invisible gloves.” There are reflections, there are paintings, there is the foreboding sense that “it will rain,” in Mejer’s words. But what if the possibility could be different? Not to be too speculative, but I wonder if the rain is inevitable, if Mejer’s world or worlds will inevitably be full of clouds and morbid air, as she calls it in one poem. If it’s possible that there’s an uncertain future, that the world of the past can be washed away, then perhaps we readers will have to wait for Mejer’s next collection to see this lovely truth.