Fado, Feminism, and Faith in Marina Carreira’s I Sing To That Bird Knowing He Won’t Sing Back

13.02.18

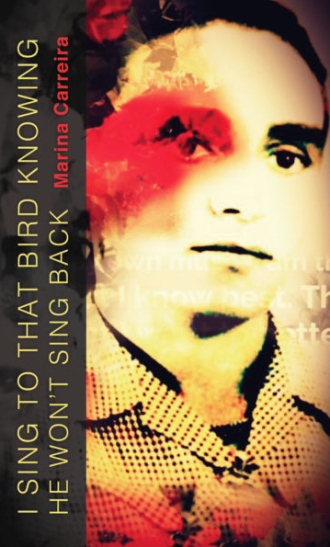

I Sing to that Bird Knowing That He Won’t Sing Back

I Sing to that Bird Knowing That He Won’t Sing Back

by Marina Carreira

Finishing Line Press

$14.99

In her chapbook I Sing to That Bird Knowing He Won’t Sing Back, Portuguese-American poet Marina Carreira draws from the vast spheres of her experiences to investigate issues concerning feminism, immigration, faith, and politics. It’s an ambitious first publication; one that succeeds, in part, because of how true it remains to the essence, both personal and cultural, both literal and figurative, of fado, the Portuguese genre of music, as a form of artistic expression.

Fado, which has been inscribed in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists, is perhaps one of the best recognized ambassadors of Portuguese culture abroad. The recognition by UNESCO is only one of the ways that fado has gained popularity outside of the borders that outline the small west-European nation. Legends of fado like Amália, and more modern artists like Dulce Pontes and Mariza, have garnered attention and toured internationally.

Lesser known is the other, older definition, for the word fado. It’s one that comes from the Latin word fatum, meaning oracle, premonition, or prophecy. In modern Portuguese, certainly in conversational Portuguese, fado is a word almost strictly used to describe the musical genre. Yet the primary dictionary definition for the word is destiny, as in a superior force that aims to control all events. Another definition describes it as that which must necessarily happen, regardless of human desires.

— // —

In her collection, Carreira succeeds in creating a new type of fado — one that recasts old conversations in a new light, with fresh language to signal how both versions can be parallel. She writes, for instance, of fado as a theme that she revisits throughout in various and rewarding ways, even as each of the poems is presented as its own fado, with its own focus and pace. The overall effect is that of a mosaic; the collection follows along a narrow path to narrate a complex image of first-generation existence. For instance, in the poem “Fado for My Sister,” Carreira writes of a way of processing the idea of fado, a definition disguised as a premonition: “A beautiful song; sad/ends bad, but we know all the words.” Later in the same poem, we encounter the unanswered prayer from which the chapbook takes its title:

Behind the curtain of winter I sing

to that bird knowing he won’t sing back,

and wonder if you made it home last night,

if you remember that thing you said last week

that made me laugh until I cried.

The collection surprises with its novel ways of treating familiar aspects of the immigrant experience. At turns, we learn of Dona Rosa who will “sing and sing/until the February sun lifts its rays/off the Tejo,” even as just a few poems later we find a different inspiration for the author’s fado: “her eyes, two pebbles rippling a mended lake. All night,/the neighbors heard her sing, She loved him, oh she loved him, but he loved/Anabela instead.” Sometimes, the fado is offered as a possible solution—“Won’t you, oh won’t you,/sing me this song?”—to an existence suspended between two continents, across borders both real and imagined. We don’t know whether these poems take place here or back home, in worlds real or imagined. That they could inhabit either or both adds a particular depth. We are brought to face the immigrant curse, the hyphen that both bridges and divides the Portuguese origin from the American existence. And the fado serves as more than just theme, it becomes the very melody accompanying these poems.

In “Christmas Eve Fado,” Carreira explains how fado functions as a hand-me-down she inherited: “When I was four//you’d play Amalia/over and over//again until you couldn’t/bear to remember//the way the waves in Nazaré/roll, foam//ribbons before/breaking.” Permeating the poems are echoes of the homeland, nods to the people lining memories on either side of the Atlantic. There’s an irony here that concerns the idea of Carreira’s fados existing in a foreign tongue, but that irony only further contextualizes the collection as a little of both shores, but never specifically one or the other.

— // —

To hear fado in a Lisbon fado house, as it is performed live, is to have an out-of-body experience. After a late dinner is served, the lights dim. House wine finds the glass like a willing partner. As delivered by a voice simultaneously powerful and frail, and as accompanied by the strumming of guitars, the directness of the emotion travels the darkness to reach the audience in late-night spaces converted from serving meals of a different sort. For the audience, fado comes to nourish. It arrives like comfort food for the soul. An echo of a history that incorporates both the validating victories and debilitating defeats of a country that traces its roots back to the 12th century.

Tattooed into fado are lives of greatness but also moments of cruelty. The fado synthesizes all of that to present human existence as a river of song. If a bird could squeeze its thin ribs around a sonnet and squeeze out only the pulp for itself, its song would be fado.

— // —

The Portuguese-American experience, and subsequent concerns of identity that arise, are a strong influence on this collection, not only in the historical context but also in matters concerning how that history repeats itself on foreign shores. For Carreira, who is deeply interested in the role of the motherland as both source of origin and foreign entity, questions of feminism in context of a culture with a long history of repression appear at every turn. For instance, in “Fado for the Marias,” she channels the traditional “name of all Portuguese mothers” to question accepted gender roles: “Marias who make/your favorite sandwich … your hotel bed precisely/how you like it.” Carreira later reminds that these are the same women who were cast as “witches and saints,/whores and queens/raped and ruined/by holy men who renamed/the goddesses, found Jesus/struck wombs with crosses, flags.” In the poem, those same Marias are celebrated as complex figures, with individual lives and desires that exist beyond the confinement of their expected roles: “Maria first kissed/the nape of your neck, showed you/what maracujá tastes like/how a viola cries.”

These images, powerful in their own right, are further effective for the use of the name Maria in context of the Three Marias, the group of feminist writers who, labeled as immoral abusers of the privileges afforded by the Portuguese fascist regime, worked against censors to create the landmark work New Portuguese Letters. The Marias were eventually arrested, their book banned. Carreira takes on their task in a different setting, though her mission is distinct and her method less direct. As when she channels the Virgin in “Fado da Virgem”: “I never asked/but received/without refusing.”

In those moments, it’s difficult not to think of this book as picking up a conversation originally started in Portuguese. In revisiting her motherland’s history and tradition, religion too, Carreira is carving a new path for a Portuguese-American feminism. One evolved from the Portuguese movement, informed by the immigrant experience and offered here in a fresh way by a promising new voice.

— // —

While Portugal suffered under the longest fascist dictatorship of the twentieth century, fado was seen by the establishment as potentially subsersive. The Portuguese regime embraced repression, not exaltation. Fado’s simple structure valued the individual artist’s interpretation, creating a unique relationship with the audience that, from the perspective of the state, threatened a social harmony built on conformity. As early as 1927, supervision of venues and public entertainment spaces was enacted into law. The myth of the fado being used as a tool of the regime is borrowed from interpretations of how art and sport were leveraged by regimes elsewhere. The Portuguese experience was different, in this regard.

From its inception, fado has represented urban life: the tavern, making a living off the sea and poverty. Saudade, of course. But even as fado lost some of its improvisational nature under the regime’s supervision, it retained its themes. Its popularity grew. In moving fado beyond the limitations of a single language, Carreira is opening it up in a revealing new way.

In the fado house, when the music pauses at the end of a line and the singer holds the note, that’s hope. It’s humanity’s index finger reaching out across the skies to touch the starting-line of destiny.

— // —

Carreira channels that urban history in the section titled “Fados Do Ironbound.” These poems are addressed to the Newark neighborhood that has, since the early twentieth century, been home to thousands and thousands of Portuguese immigrants. Carreira writes to the Bricks (Newark is nicknames Brick City) and to Penn Station, to Ferry Street too, the vein of the neighborhood that every June is renamed Portugal Avenue for the duration of the weekend-long Portugal Day Feast. And even as she writes of this neighborhood, Carreira calls on the fados sung by Portuguese artists as explanation for the American world around her: “Boat and child in hand,/you remain still as stone,/dreaming of guitarras/e a luz tremula e frouxa/das velas.”

As a lasting image, a keepsake from this collection, we are left with the last stanza of the closing poem, “Fado for How I’d Like to Think You Remember Me”:

Imagine a mare splitting the tide

with its charging, the blue moon

cast-iron on its back as waves break through

that glorious gallop: the astral frenzy

of a Portuguese guitar.

–––––

Hugo dos Santos is a a Luso-American writer and translator. He has been awarded fellowships by the MacDowell Colony and the Disquiet International Literary Program. He is the translator of A Child in Ruins (Writ Large Press, 2016), the collected poems of José Luís Peixoto. His work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and has appeared in various publications in the U.S. and Europe, including upstreet, Public Pool, Lunch Ticket, Queen Mob’s Tea House, DMQ Review, and elsewhere. He is the author of ironbound – a blog.