Facing the Past: An Interview with Travis Jeppesen

27.01.15

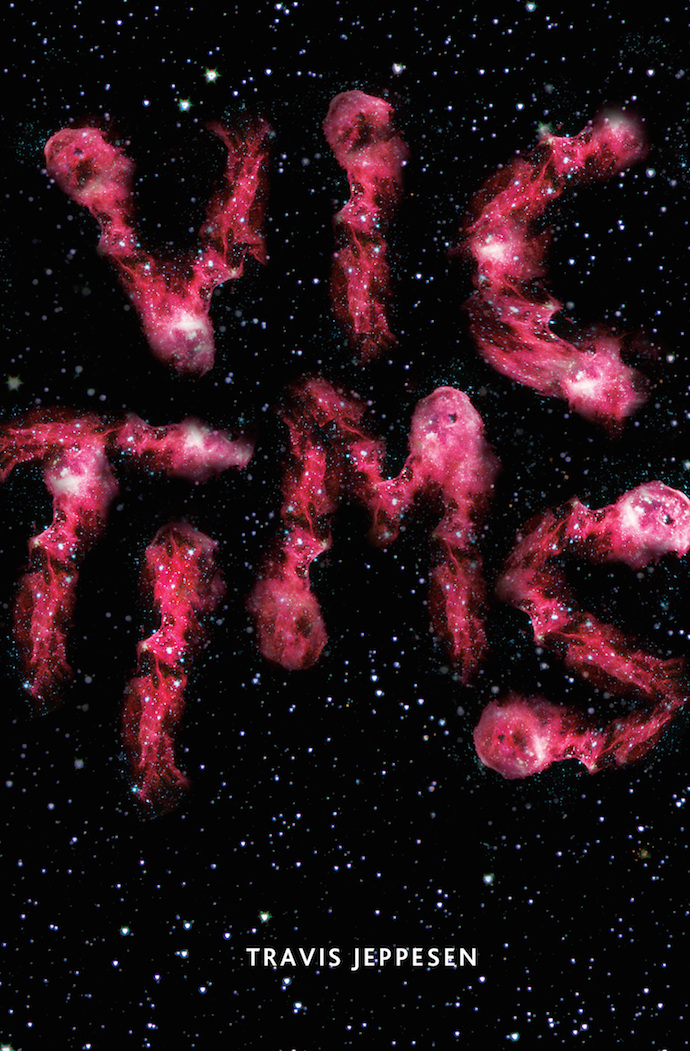

Over the span of a decade and then some, Travis Jeppesen has manoeuvred words into an uncanny body of work. He has published three novels–Victims, Wolf at the Door, and The Suiciders (one of my favourite books from last year)–two collections of poetry, and has written plays and collaborated with queer legends like Ron Athey and Bruce LaBruce. He also a prolific critic, reviewing and dissecting art in all its forms for a variety of publications.

When I think of Jeppesen’s work, it feels like this living thing – this fluid, shifting thing that could bite your arm off. It’s wonderful. His debut novel – Victims – had the honour of being the very first novel that Dennis Cooper chose to launch his Little House On The Bowery catalogue, no small praise indeed.

Victims came into the world in 2003 and is now being pressed in a new edition by the Brooklyn based ITNA Press. As Kevin Killian points out in his forward to the new version of Victims, a lot has occurred in culture in the last 11 years.

I spoke with Travis about how he feels about his debut novel a decade on from its original release.

TM: How did the new edition of Victims come about?

TJ: The book seemed to have reached its end with Akashic. The first print run had sold out, so then they produced a pretty shabby P.O.D. edition that they just obviously didn’t take a lot of care with – I mean, it looked like it had been done on Microsoft Word or something. There was no fanfare or publicity over this second run, they obviously didn’t care about the book at all, they were just sort of nominally keeping the book in print. I do happen to care about my work, even though it was my first book and I wrote it when I was very young. Chris had asked me if I would be interested in doing a book with his press, but this was shortly after The Suiciders had come out and I had already agreed to publish All Fall with Publication Studio, so I didn’t have anything I could give him. I arrived at the idea of re-issuing Victims when I was in New York last spring in conversation with Bruce Benderson, who is also doing a book with ITNA. The idea is simply to give the book new life, not just keep it “in print,” gathering dust in some storage shed. Chris, being a writer himself, understands this, he works hard, he’s very much on top of things, he’s enthusiastic, and he’s bringing a lot of great writers into the fold. All of these things seem very promising.

I’m interested in how a piece of existing work changes to the person who made it. I remember reading interviews with you after I first read Victims a few years back, and it seemed like the work had come from an intuitive place, of boredom and curiosity. I remember a specific interview where you said that you couldn’t recall all of the things that were in your mind while you were writing the novel. How do you view Victims now as opposed to when you wrote it?

I was afraid to go back to it, because I hadn’t read it in so long. Of course, writers don’t sit around re-reading their old books all day – at least I’ve never met one who has. You finish it, it gets published, you move on to the next thing, you forget about it, right? So going back to something that I wrote when I was so young, I thought it would be majorly embarrassing, you know, you have so little life experience at that age, what could you possibly bring to the table? I was happily surprised when I was re-reading it for the ITNA edition. You know, I would never disown it. There is a crudity of language in some parts, but that contributes to the musicality of the whole – and that juvenile crudity is obviously important to me, as anyone who’s read The Suiciders knows. But I think the form of the thing – which was arrived at completely intuitively, in the process of writing – that’s what makes it such an exciting book for me. It does something, and it manages to still say something.

You talked about how The Suiciders was born out of failure. What are the failures that you see in Victims?

I think the shortcomings, the mistakes, the crudities in writing are what give writing its texture. I’m not interested in smooth surfaces. I had a chance when re-releasing this book, Chris gave me carte blanche to make all the edits that I wanted, to make the book read or sound “better.” I changed very little. Art magazines, for example, are full of examples of good prose – none of it is very interesting! As it really is the heteroglossic domain, the novel is the place where good and bad prose and whatever it is that comes in between may flourish.

Your fiction feels very much like it is inspired by other mediums of art as opposed to just other writing and writers. What other artists or pieces of feel like peers to you? Who have you been enjoying or inspired by recently?

Well, it is, though I also read a ton of books. Film and visual art have always been very important to me. Though lately, I would say I’m more inspired by nature, by real life, than any one particular medium or artist. I was asked to write an essay about my inspirations for Frieze this summer, and rather than doing the standard thing that most people do of listing their favorite books or movies or whatever, I wrote all about my best friend, Brian Tennessee Claflin, who passed away this summer. My next book will be all about him. Sure, he was an artist as well, he made a lot of great work. But my relationship with him wasn’t all about appreciating each other’s work, it was about enjoying each other’s company – inspiration on a more quotidian level. Traveling, being with friends, or walking down the street alone and just being in my own thoughts – those are the biggest sources of inspiration for me these days.

I’m sorry to hear about the death of your friend. I read your piece about him. He sounded so interesting. When you say that your next book will be about him, is that a conscious choice – you’ve decided to create a tribute? Or something else? Something you just feel compelled to do instinctively. I guess as well if you see your work as helping with things like grief, catharsis etc?

I went crazy from despair this summer and was unable to do anything else writing-wise, so I had to travel. I went on a long trip that I just got back from, I was traveling for two months rather aimlessly, just drifting through the Mediterranean, staying at cheap hotels and deciding where I would go next a day or two in advance. And this helped me start writing again. Travel is therapeutic for me in that regard. And when I started writing again, this book just started to come into being on its own, it wasn’t one of the ones I had planned before, but I realized the necessity of doing it — that it was the only thing I was capable of working on at the time, and now that I’m in the thick of it I feel compelled to finish it.

There’s something about your writing that feels very influenced by music … do you listen to music when you write? Or do you have to write in silence?

I used to listen to music when I wrote, but in the last few years I haven’t been able to do it as much. The silence is loud enough for me, I guess. I was actually trained as a musician and was playing music since I was six years old, so the I think the musicality of my writing is just an inherent thing that happens unconsciously. Having said that, I think it’s a very important aspect of writing that is often ignored, and I’m very sensitive to it. I can certainly tell when I read a writer who has a “tin ear”!

With regards to the musicality of your writing, I was thinking about improvisation. It sounds like a lot of your work is based on intuition during the process. With your books, where do you start? Do you rely on preplanned structural stuff, and then improvise and work your way around that, or is it more a case of just writing as it comes to you when it does and letting instincts lead the way completely?

When I’m writing, I often enter into a sort of haze or a trance state, which is why it’s hard for me to answer these questions about my process after — I am not able to remember so much about the actual writing in my mind, I can’t re-create it, it’s like the moment has been lost. Also, things are cobbled together. I’ll get my best ideas when I’m technically not writing at all, when I’m walking down the street, make notes in my small pocket notebook and type them up at home later. Then I amass tons of material, realize I have to do something with it, print it out and start re-typing, throwing things out along the way and altering things. Every book is different, too, in that regard. So the writing of Wolf at the Door was a lot more concentrated and straightforward, most of it was written during a residency when I was relatively isolated much like the characters I describe in the novel. With The Suiciders, rather than fighting the sorts of 21st century distractions that so often pull one away from writing, I arrived at the decision to make the writing itself a product of those distractions, to render an extreme satire of short attention span culture. So to answer your question, yes, there is a lot of preplanned stuff — though nearly all of it manages to get thrown out along the way, that’s when the actual writing takes place.

This process often takes several years. I’m very rigorous about it because I have to be. I just got back from a long trip that lasted two months, I was traveling through the Mediterranean. I was doing my normal thing, going along, making notes, organizing them when I was at the hotel later. Then I decided to get more organized, so I started to make lists. Simple things, like one was a list of how many countries I had been to — I had never figured it out in my mind, so I sat down and made a list and found out I’ve now been to exactly thirty countries. Another list was books I’ve had ideas for and I’ve been making notes for, off and on, planning, over the years. Although I’m only ever working concentratedly on one book at a time, there are still all the others floating around somewhere in my brain, I get ideas for each of them sporadically, that’s what I carry around the small notebooks for, I have no memory so I have to write the ideas down immediately, then I have a folder for each of the future book projects on my computer at home, I go home and transcribe the notes and put them in the folders to work on later, when it will be that book’s turn. So I made a list of all the books I’ve been working on, in this very unofficial way, over the years, and it’s twenty-four different books I found out. So as you can imagine, I found myself to be very much in a race against time.

So those books are all being planned, but often the planning gets tossed out the window once I sit down and the actual writing occurs. You have to be comfortable enough, over-familiar enough, with your own material to be able to do that. To let it go, toss it out the window so that you can then re-introduce it in a more casual way that feels less forced. That’s the best way I can explain it. I guess it’s just the old cliche of destruction and creation feeding into and off of one another. Being organized about it is my way of trying to control it, to make it less of an illness. If I weren’t able to do that, I would probably just go crazy, all these jumbled thoughts clouding my brain.

Has your work in Academia had an influence on the way that you write? If so, how?

No, not at all. If anything, I would hope the reverse would be the case, that the work I’m doing would encourage more risk-taking and imagination in academic writing, though of course I’m not going to over-estimate my influence. I have some brilliant colleagues and supervisors in the Critical Writing in Art and Design program at the Royal College of Art, and they’ve all been sympathetic to the work I’m doing there. For me, it’s been important to assume an activist position, to assert that art criticism is an art form equal to painting or poetry or fiction. This is the stance I’ve always taken and will continue to take. I know it’s a minoritarian viewpoint, but I hope it will spread.