Facing Infinity: Yayoi Kusama’s Life & Endless Rooms

28.02.17

Entering the world of artist Yayoi Kusama is like entering an endless galaxy. Repetition, pinpricks of light, phalluses, polka dots, mirrors, over and over and over again.

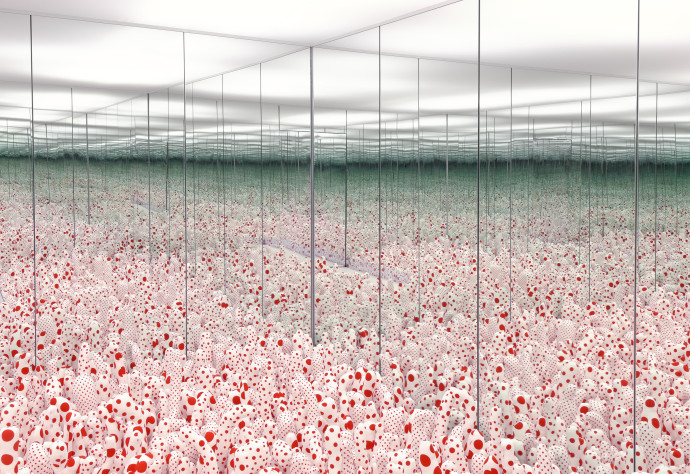

The first mirror room reflects polka dot phalluses forever under a bright white light. My face is in the mirror, my body is in the mirror, and I am reflected too, over and over again until my form becomes meaningless.

Another room features an electric purple rowboat covered in soft phalluses. An image of the same rowboat is pasted on the wall over and over again, 1,000 times, 1,000 boats, millions of phalluses. It is dizzying, warbling. I want to touch the oars, I want to blink away the lights.

The second mirror room is an infinity of lanterns. I stand in the pure darkness until a single lantern is illuminated. The lantern is reflected four times over, giving more light. Another lantern begins to glow, then another, then another, until I am obliterated in the pinpricks. I catch my breath in the darkness. I can no longer see my body. All I can see is the light.

All around me, reporters snap pictures. This is the press preview for the biggest retrospective of Kusama’s work in America at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden: Six infinity rooms, 70 works spanning her career, tracing her trajectory. The BBC takes photos of the curator. A man from the newswire service AFP films me entering a mirrored room because I’m wearing all black and “shooting this is tricky.”

I’m not above this. I snap pictures too. In the rooms, I take selfies — this is a luxury. At the press preview, we can see the Infinity Rooms multiple times. We get one full, luxurious minute before an attendant knocks at the door, destroys the reverie. The public will see the rooms in 30 second increments, a shortness that feels shameful. The rooms are a place you want to stay as long as possible. It becomes an addiction to obliterate yourself within them.

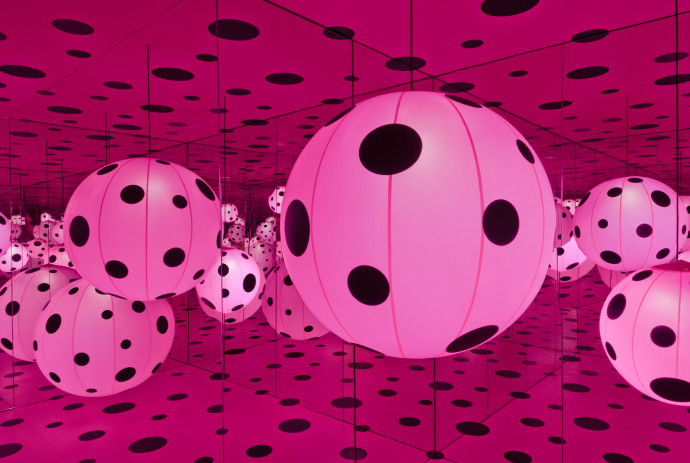

The third room reflects gigantic electric pink balls with black polka dots. This one feels easy, less intense, fun. The pink light is gentle and kind. The giant pink balls are reminiscent of Ikea, a replication of a concept over and over and over again until they saturate the mind.

Another room, “The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away,” is simple but exquisite, Kusama at her height. It offers infinite pinpricks of colored lights, a room that goes pure black and then explodes into dazzling light around me. This is the room that brings me to tears, and I return to it three or four times, standing in the center of a galaxy that is constantly imploding and being reborn.

The walls between these infinite rooms are lined with early Kusama: Incredible amoebas, stills from her nude “Happenings” in the 1960s, artistic orgies overlaid with her signature polka dots that got her banned from some countries and welcomed in others. Also on display: Her early Infinity Net paintings, which are dizzying up close, overwhelming. Photos of a younger Kusama placing polka dots on bodies and animals dot the exhibit.

Kusama, born in Japan’s Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture in 1929, kicked off her career stateside by shipping 12 paintings to Georgia O’Keefe. O’Keefe received the paintings and encouraged Kusama to find a way to America. Once here, she made a name for herself in New York for these Infinity Nets.

Kusama describes the creation of these paintings in her autobiography, Infinity Nets:

I got up each day before dawn and worked until late at night, stopping only for meals. Before long, the studio was filled with canvases, each of which was covered with nothing but nets. In time my friends grew uneasy and peered at me with anxious blue eyes. ‘Yayoi, are you all right?’ they’d ask, genuinely concerned. ‘Why are you painting the same thing every day?’

In fact, I often suffered episodes of severe neurosis. I would cover a canvas with nets, then continue painting them on the table, the floor, and finally on my own body. As I repeated this process over and over again, the nets began to expand to infinity. I forgot about myself as they enveloped me, clinging to my arms and legs and clothes and filling the room.

Here is the dark belly of Kusama’s work. While her work, on the surface, can seem playful or an homage to pop art, it is a process of managing her own mental problems, which she speaks about freely.

I make them and make them and then keep on making them, until I bury myself in the process. I call this process ‘obliteration’. I don’t want to cure my mental problems, rather I want to utilise them as a generating force for my art.

This desperation for obliteration marks almost every single one of Kusama’s artworks. She turns to repetition to work through everything from her fear of sex to her fear of prepackaged foods. The soft phalluses she created endlessly were meant to help her overcome her rejection of the male sex organ, while the polka dots were a way to hide.

By covering my entire body with polka dots, and then covering the background, I am in with polka dots as well, I find self-obliteration. My own mass is therefore absorbed into something timeless. And when that happens, I too am obliterated.

When I request an interview with Kusama before the opening, I am told she is unavailable. Partially, that is because I don’t write for the Washington Post, and partially that is because she is living in a mental institution by her own choice.

One day I suddenly looked up to find that each and every violet [in the field] had its own individual, human-like facial expression, and to my astonishment they were all talking to me. The voices quickly grew in number and volume, until the sound of them hurt my ears. I had thought that only human beings could speak, so I was surprised that the violets were using words to communicate. I was so terrified that my legs began shaking.

I struggled to my feet and ran as fast as I could, all the way back to the house. I was almost there when our dog took up chase, barking at me – in human words. Astonished, I tried to say something, but now my voice was a dog’s voice. Pale and trembling, I wriggled into a cupboard and closed the door and only then was I able to breathe.

She was committed to the institution in 1975 and has remained there since. Each day, she leaves the institution to work in her nearby studio. Her initial diagnosis was that of obsessive compulsive disorder and “depersonalization” — a disorder which disconnects one from their own body.

To see her body of work laid bare, finally, in a narrative that matches her life, is beautiful, complex, overwhelming. I feel, at times, deeply sad for her suffering, though her output is stunning. It feels a retrospective of this magnitude should have happened sooner. We save these women until they reach old age: like Louise Bourgeois, Kusama is 87 years old before she hits this peak in America, before they sell mugs of her work in the gift shop of the museum.

To see her work in this way feels rare. I have been waiting for it for so long. The first impulse is to take as many pictures as I can, one that makes me feel sick with myself at first. The second impulse is to experience these rooms the way she meant for me to.

Phoneless, in the room of galactical infinite lights, a meditation takes over. The rooms expand endlessly, my body is obliterated, I am lost in wonder at what she has created, a room on the edge of infinity where you no longer exist.

I feel as if I am driving on an endless highway, all the way to my death. It is like drinking thousands of cups of coffee cranked out of automatic dispensing machines. And until I reach the end of my life, I will, through no choice of my own, aspire to all sorts of feelings and visions, while at the same time fleeing them and seeking obliteration.