Cassandra at the Oscars

27.02.17

My friend Lisa Motherwell put it on her Facebook feed, what we were all feeling: “Can someone please open up another envelope and say it was a mistake and Trump didn’t win?”

I’m here in Los Angeles on the verge of the Oscars—my wife and I are attending the LA Art Book Fair—and I’m thinking about how Hollywood has changed since last year when we were all so furious about the race issues that the 2016 Oscars threw into a hideous prominence. If you’ve read this far, you’re one of those who will recall that last year at this time the hashtag was #OscarsSoWhite, since not a single nominee of the twenty slots was filled by a black actor. This year the situation is somewhat different, though the rumble is still in the air, with the fans battling over the super-white and kitschy La La Land unleashing white shock and awe on the actually more deserving black art picture Moonlight. (I never thought till writing that sentence that both titles share a certain lambent glamor, a fleeciness that perhaps reveals a commonalty in their otherwise very different styles? Well, the first thing you learn about the movies is that they’re images, shadows of life, thrown up onto a screen, and that then they vanish, forever, or at least until Martin Scorsese’s foundation comes in and commands, “Restore that celluloid.”)

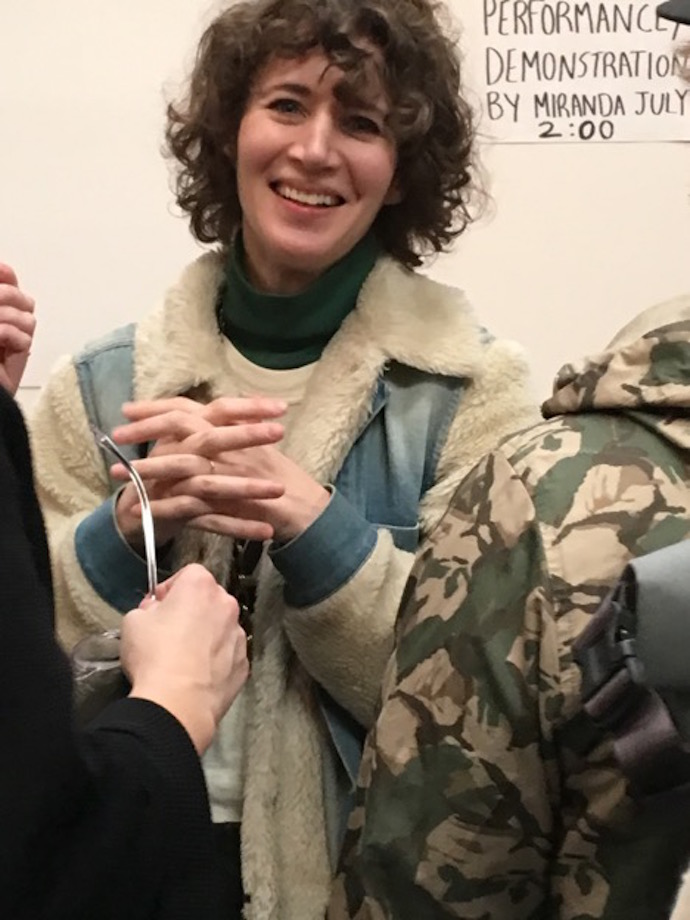

At the Art Book Fair, Dodie asked Hedi (who was manning his own book table for Semiotexte) if stars come to the Fair often. He mentioned the name of some art stars, but that wasn’t what she was asking about. Other Book Fair vets remembered Bette Midler coming, Kristen Stewart, Lena Dunham; I saw none of them. I had my autograph book in my pocket either way. I got Thurston Moore’s autograph within five minutes of walking into the Fair. But I needed more of an Oscars tie-in. A ginger-headed hipster with a strangely black bush of a beard was confiding in his girlfriend right next to me. I noticed that the crowd moving through the refigured rooms of the Geffen Contemporary Museum had slowed down. We were all still walking, but at an ant’s pace. Like we were in a swamp and our feet were caught by wet hungry sand. The hipster explained, “He’s from the UK and his father was gay and won the Oscar, and now his new movie’s about his mother.” The beautiful gray-eyed girl pulled down the hood of her white satin jumpsuit and widened her eyes. “And he’s up for an Oscar for best original screenplay.” At that moment my brain caught on and I realized we were paused before a performance stage on which another bearded man asked us if we had ever heard of Miranda July. At this point it was solid molasses, people were pressing in on me so that I was having 70s flashbacks of that awful Who concert in Cincinnati, and I snaked my hand down to my hip picket to make sure that my wallet was still there. We were all facing the stage and holding up our iPhones in the air hoping to be able to get a good picture of Mike Mills and Miranda July. When I saw her, I was like, “Note to self, Miranda July is so pretty she could be in the movies,” while another part of myself was recalling July’s long career on both sides of the camera. But in person a keen intelligence reveals itself on Miranda July’s face. I told myself, I hope Mike Mills wins the Oscar so the camera will show Miranda July next to him sitting down and hugging him, though I remember reading many publicity articles about how the two artists who are nothing alike lead separate lives and don’t live in each other’s pockets. They’re not Heidi Montag and Spencer Pratt; they’re more like Sartre and de Beauvoir—intellectuals, free spirits attuned to higher frequencies. I’ll leave it to seasoned showbiz reporters to describe July’s performance at the LA Art Book Fair. I heard shrieking but cannot say whether it was she who was shrieking or we her fans.

I flashed back to 1999, the last time I was in LA the day of the Academy Awards. I flew from San Francisco to LAX in the morning. March 21, 1999 my diary tells me. We forget that years ago the Oscars were in March, during the spring solstice, the astral time of year of rebirth and green shoots of leaves and moonlight, like Oberon,

And never, since the middle summer’s spring,

Met we on hill, in dale, forest or mead,

By paved fountain or by rushy brook,

Or in the beached margent of the sea,

To dance our ringlets to the whistling wind,

But with thy brawls thou hast disturb’d our sport.

By ten a.m., the crowds flanking the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion had swollen in masses each with their point and shoot cameras, their autograph books, hardy and experienced hikers with campstools. They were in for the duration, ready and anxious to see their stars, and I drove through the streets, marveling at the men women and children in these oddly socialized groups, flipping through movie magazines, arguing about what was going to win that evening. It was a big race between Saving Private Ryan and Shakespeare in Love. It was the evening that Elia Kazan, aged 88, won the lifetime achievement Oscar and a divided Hollywood showed its face briefly, the Leftists sitting on their hands during the rousing standing ovation that Kazan was given. I was on my way to meet the LA-based photographer Catherine Opie to collaborate on an assignment from NEST, the innovative magazine of interiors, on a piece about Julie Newmar’s garden in her LA backyard. Yes, Newmar was an actress, yes, she was part of Hollywood’s studio system during the blacklist era, yet despite her eternally foreign, not to say unearthly appeal, she escaped being named during the blacklist by Elia Kazan or any of the other McCarthy tools.

Across the street stood the little Brentwood cottage where Marilyn Monroe died in 1962, and the late Rita Hayworth had lived on the same block. And of course Nicole Brown Simpson was killed a block or two away. Cathy wandered, observing the garden from the ground up, as I scribbled into my notebook all the divinely inspired things wise Miss Newmar told me. Over the city festive lanterns swung and the men and women of the beautiful anointed had their tuxes ironed and their Armani gowns unfurled. Nest published my musings on “Julie Newmar’s Garden,” with Cathy’s pictures, in a summer 1999 issue, from which I now quote,

“Did you ever go to the Oscars?” I ask her. “Once,” she says. “Once only. In a garden you can divest yourself of dead energies. At 5:00 o’clock the light poking through the leaves grows lucent, chartreuse… Oh, there’s going to be a rose named after me,” she exclaims, delighted. “My life’s dream.” A sign taped awkwardly over her computer in her office says, “I am not afraid.” I’m lying there on the chaise longue explaining Julie’s career to her, watched by these two extraordinary-looking people, Julie and her son John. “You are the bridge between the human and the divine,” I blurt out. “The only thing I do is leap over the fears,” she says. “And I pray. And I deadhead the pansies.”

That was last century, but LA hasn’t changed that much. 2016 was a year of puzzlement for me; perhaps for you too. Chief among my puzzlements was the election of Trump. Like Cassandra, I kept telling people the worst was about to happen, but on the other hand not enough people liked Hillary enough to allow her to win. She was sort of like Gwyneth Paltrow enduring the curse of Oscar after Shakespeare in Love. A hatred of her crept over you like a turtle’s shell, grew impermeable—a “motiveless malignity” of the sort Coleridge ascribed to Iago.

My next puzzlement was the movies up for the Oscar! I’m an idiot but I enjoyed Arrival very much, and then in the car home Dodie asked me what I thought of the “twist.” I braked in panic. “What twist?” I’m the only one I heard of who didn’t understand there was a twist. [SPOILERS AHEAD.] I’m forgetting now, but I think that the little girl Amy Adams is mourning at the beginning of the show has not even been born yet when it begins and that Jeremy Renner is the father? No, didn’t get it. I did understand she was ready to love again, despite the death of her little girl. But that was wrong; but that was the cuter ending if you ask me! I loved Moonlight, but was I wrong to come away thinking that when Chiron (now played by Trevante Rhodes, and now an adult drug-dealer) tells “Kevin” that he hasn’t had sex since the night that Kevin gave him a hand job, that he was lying? It doesn’t make sense, and as a Kevin myself I’m surprised the screen Kevin fell for it. Simply put, Chiron was too cute to go unlaid for so long, so why didn’t they get a plainer actor to play him if they really wanted us to believe in the story? And yet I understood, finally, yes, you are supposed to believe it, because the movie is about how bullying ruins everything. More puzzles? Why do the wunderkinds make homages to classic Hollywood musicals and hire the actors who can’t sing or dance? I sat through this already, back in the 70s, when Peter Bogdanovich asked Burt Reynolds and Cybill Shepherd to carry a Cole Porter score in At Long Last Love! Or wait, what was that Coppola film with Nastassja Kinski singing Tom Waits songs? [END SPOILERS.]

And like Cassandra, I was telling everyone that La La Land would win, it had to, and leading up to the finale of the Oscars the momentum of award after award going to Damien Chazelle’s musical pastiche, convinced me even further. I was jumping up and down and clapping when screen legends Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway came out to present the Best Picture, and then came the now-famous confusion and what seemed like La La Land getting everything—(and that one producer thanking his “blue eyed wife”)—and then like a complicated Pina Bausch dance those little envelope things were being whisked around the stage by gnomes, and suddenly that tall bald man said, “This award really goes to Moonlight. We’re not kidding you,” and it was like one of those great movies where the simultaneous movements of many actors reveal a larger truth. It was a theatrical moment as great as the sublime sequence in Nashville when Keith Carradine sings “I’m Easy” in a crowded nightclub, and each woman in the audience thinks he’s singing just to her, and then each realizes, shucks, he’s singing to the girl behind me. And no, I don’t mean the Nashville in which Rayna Jaymes got killed. That’s the remake of the movie in which Barbara Jean gets killed.

Really I’ve never seen anything like it. I must review the footage to see if the camera ever actually showed Mike Mills and the white, perky Miranda July, the new Left Bank duo of the enlightened age of Portlandia.