Eyeball the Stain

05.04.12

Emil and CeCe are visiting for the weekend from Minneapolis, and they have the guest room where the painting is. Few paintings attract me like this one. I sit in the living room by the flat screen and listen to cars pass and bus doors zip outside under the birds’ twitter, but the two are still sleeping. It’s their room now, and I can’t impose.Waiting is the game these days, from checkout to elevator, to doctor’s appointment, to the room with the painting. I’ll wait until Emil and CeCe open the door. When they are finished showering and applying scents, I’ll look. And I won’t make any commitments until Emil and CeCe make their entrance. No commitments beyond watching the sun pixelate its way across the mother-in-law’s tongue.When they do enter, CeCe is in a green-flowered top with see-through openings, and the see-throughs are filled in by her yellow T-shirt underneath. She has a baby-doll complexion and every curve where it should be. Emil wears nondescript guy stuff, green T-shirt and jeans, just like he did in college when we roomed together. His hair is moussed forward and stuck up in the front. They’re cute together.

Emil and CeCe are visiting for the weekend from Minneapolis, and they have the guest room where the painting is. Few paintings attract me like this one. I sit in the living room by the flat screen and listen to cars pass and bus doors zip outside under the birds’ twitter, but the two are still sleeping. It’s their room now, and I can’t impose.Waiting is the game these days, from checkout to elevator, to doctor’s appointment, to the room with the painting. I’ll wait until Emil and CeCe open the door. When they are finished showering and applying scents, I’ll look. And I won’t make any commitments until Emil and CeCe make their entrance. No commitments beyond watching the sun pixelate its way across the mother-in-law’s tongue.When they do enter, CeCe is in a green-flowered top with see-through openings, and the see-throughs are filled in by her yellow T-shirt underneath. She has a baby-doll complexion and every curve where it should be. Emil wears nondescript guy stuff, green T-shirt and jeans, just like he did in college when we roomed together. His hair is moussed forward and stuck up in the front. They’re cute together.

They tell me they want to mosey their way to the bus stop and take the No. 147 down to the Loop for the river dyeing, which I can’t imagine can be good for the environment no matter how harmless “harmless natural coloring” can be to anyone’s potential drinking supply. Anyway, I’ve seen it all before, and it always looks neon green to me past Labor Day. You know, I’ve got things to do, I say, and with the global positioning system they’ll find their way.

They stay for coffee, and we all mention that restaurant from the night before. She liked the half-order of pasta with smoke-seared octopus, and he had some ravioli in a what-do-you-call-it sauce, but he can’t remember what it was, and the thought just drifts there until we all focus on the drinks we had at the 1930’s bar. Over our shoulders there was a field-scene mural in turkey browns and dried-stem vanillas that looked to be at home in northern Wisconsin, not in a trendy neighborhood of whatever-generation-they-were in their mullets and beards, the girls carrying purses with turquoise-colored accents and wearing gold sandals.

It’s warm for March, record-breaking. The air conditioners aren’t working yet, and I let my mind wander, thinking what a time it would be to be heavenly, to be someplace else, maybe in Europe on The Grand Canal zooming in a speedboat and breaking waves in the no-wake zone. But I’m not, and they leave, so I can enter the guest room at last.

Maybe it’s my Midwestern background. I can look and understand. It seems to me it’s the season for gawking and reflecting. An Episcopal priest, Kelly, had painted it years ago, and my elderly friend, who died last summer of a cerebral hemorrhage, had owned it in its handmade wood frame of scallops dyed in brown, not green. It has no title.

When I look at paintings, as part of the creative-interpretive process, I have a habit of scrunching down on the loose skin around my eyes and closing tight on the orbs to see pink and brown, the white and blue of spring in the painter’s eye. I move back to see it all again, maybe seven feet away, and it does seem to make dimensional sense to me, even if I can’t tell exactly where the house is, why the hills stop right there, or how the clouds cover everything the way they do. It’s all in the looking, and that’s what I do.I wanted to say that I once met an artist, Aunt Catherine’s second husband, though I can’t remember his name. This man took me into a back room, the painter’s studio filled with easels and rectangular canvases––sofa-size––and then pointed out an easel with the canvas placed there. He pulled back the white-sheet covering, and I saw a figure. I saw a––what some would call––a contemporary figure of a woman sitting on a chair. I imagine the artist took a small jar, wet the rim, and pressed coffee grounds or rich loam onto the white, applying it with wrist rotation upon the canvas, and repeated the process, as necessary, for the desired effect.Aunt Catherine’s second husband said there was only one thing wrong with the picture. This was years ago, and I’m having a hard time remembering what that one thing was because my mind’s eye told me so many things were wrong, from the perspective to the monochrome, from the composition to any inherent sense of reality. Not that reality is required, of course, but some sense of representation is preferred, for me, to pin the image to something, to categorize it in some way for the simple fact of understanding it, the same way a student acknowledges a fact, opens his or her head, as it were, tucks the fact into an imaginary folder––it makes no difference what color the folder is––places the folder into the soft tissue, and closes the head, only to open it again for later inspection or retrieval. Some people want to keep an open mind; I keep mine open so I can close it more successfully.Don’t get me wrong. I’m ready to accept whatever the artist gives me as art, but I appreciate a hint, just as Emil and CeCe would appreciate a hint––hints for life: how to flush the malfunctioning toilet off the guest room, for example, so it doesn’t run. Emil would need to know how to twist the handle back like so or take the tank lid off and push down on the flapper for a tight seal, but only if that’s necessary because sometime it’s not. It’s the same with art. I think you know what I mean.“The only thing wrong with this painting,” Aunt Catherine’s artist-husband had said, as it is coming back to me now, “is the expression.” And when I saw the black-and-white face with scribbles and wide-eyed gouges of grounds or soil from fingers bent upon the canvas, I didn’t believe a word of what he said. It’s clear to me now, sitting here years later, he was right.

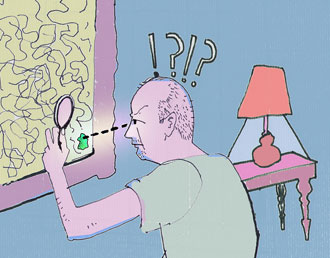

*It is stained. On the bottom left corner above the Kelly signature there is a stain. Right on the oil in the guest room. I never saw it before. Can’t tell what kind of stain it is––oil or grease of some sort. Not sure how the stain got there. Don’t want to speculate. I think they did it. Should I confront them about it? Could talk it over with them, point to the painting by way of description, and observe reactions in their presence. Wouldn’t have to do anything other than look at the stain and see how they respond. Maybe I’ll get an answer from them. Maybe they’ll explain. Or not. At least the subject would be up for discussion. Stain and satin are so close––only a transposition away. But this is a stain; no satin gloss on this painting.The green grass is full with a cement lawn-roller swath of earthen pink in the foreground. I like how Kelly juxtaposed these colors against the house and the tangle of tree limbs showering the spring afternoon. But as you look down, there’s that stain. It’s the size of a good squirt of mayo from the white plastic squeeze bottle. The squirt is wiped off, and it leaves a trail on the green paint, like a shooting star smeared with a tissue across the space of evening.It’s upsetting, and I can’t remove that feeling from me, of being derelict somehow, even when I know I had nothing to do with this patch of grease.When they come home in the late evening they’re drunk, carrying a frozen pizza box that they open, and they stash the disk in the oven for a wolf-down some seventeen minutes later. The pan is grease-covered, and they carry near-sizzling pieces into the bedroom on paper towels placed across the brown geometric duvet.They sit on the bed in the guest room, the artwork is right above them, and they toss back pizza bites and swallows.I know they appreciate staying here, even if their guest space, as I can see now––filled with zipper luggage, makeup kits, and shoes––isn’t much larger than those tiny New York City hotel rooms.Came across this painting, I tell them, invading their space, when my friend Rosy died last year. I like that one, I hear them say. Isn’t it perfect the way the branches capture the shade in contrast to the spring warmth? I ask. They chew and nod. Was that a spray of pizza grease I saw shoot upward from the soggy crust?Stopping at the painting, I scrunch my eyes within inches of the canvas. Observing is more than touching, and I pull my head almost tight with the canvas to eyeball the stain.Their munching stops.

I clamp down on my eyes again and foist screwball vision on the stain. I go over the whole tiny canvas, only yea by yea, and stoplight my vision like a red laser beam on the lower left right above the Kelly signature. I unscrunch and look at them. I scrunch again at the painting and stop. I look back at them.

They are looking at each other with guilty pizza mouths; their dark circles sag within their individual drunks.

Having seen enough, I leave the room and cater to my urge to wander down the hallway, elevator it to the lobby, revolve through the entrance, turn south, and pass the all-night convenience store, neighborhood food pantry, and Asian restaurant that smells up the warm dark. The moon is far away, and I see the faces of people who were out drinking. Whoops and hollers escape from park benches or make their way to me from inside open apartment windows from which exposed arms extend.

I won’t do it. It’s a Kelly, but I won’t sue them. Don’t think I’ll be looking at my painting very often, though. Especially with a big stain on it. I’ll have to find another favorite, thank you very much. But what are friends for if not to mess with your oil painting? I ask myself out loud.

The walk is back along the dreary hall into my apartment, and I want to go to bed. I see a note on the kitchen counter because they know I don’t have a cell phone that’s worth a darn, and I don’t use it much anyway, but you’d think an observer would, wouldn’t you?

Sorry about the stain. It’s fixed. Used dishwashing liquid and cotton swab. Night.

––Emil and CeCe

So I’m waiting to see if the stain is gone or whether it’s an advanced form of mess. I can’t go into their room because they’re sleeping, and it’s their room now. I have to wait till morning, till they make their appearance and sunlight filters across the mother––oh, never mind.

No, seriously, dishwashing liquid and a cotton swab, when applied by a sober artist, can yield fine results. Remember da Vinci’s The Last Supper and the talented conservators in Milan? Their technique, precisely.

When Emil gets up to go to the bathroom, I approach him and ask about the painting. He takes the Kelly from their room and gives it to me for inspection so I can rest the night in peace. And I do because I can. And it’s fine, and so am I. Case closed. Stain fixed. We’re still friends.

Consider adding a rule: No bedroom eating, or words to that effect.