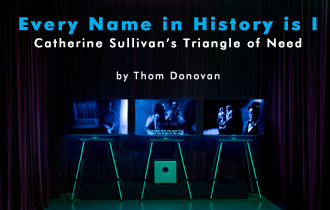

Every Name in History is I: Catherine Sullivan & The Triangle of Need

08.03.08

Do not take the Prado case seriously. I am Prado, I am also Prado’s father, I venture to say that I am also Lesseps. . . . I wanted to give my Parisians, whom I love, a new idea—that of a decent criminal. […]

Do not take the Prado case seriously. I am Prado, I am also Prado’s father, I venture to say that I am also Lesseps. . . . I wanted to give my Parisians, whom I love, a new idea—that of a decent criminal. […]

The unpleasant thing, and one that nags my modesty, is that at bottom every name in history is I; also as regards the children I have brought into this world, it is a case of my considering with some distrust whether all of those who enter the ‘Kingdom’ do not also come out of God.

––Frederick Nietzsche, from a letter to Jakob Burckhardt, January 5th, 1889, quoted from Pierre Klossowski’s Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle.

The hope is that neither the historical significance of a location nor the stylized theatrical action staged there is absorbed into the other, making a pure fiction. In the best cases character, action, and setting animate one another toward an effusion of meaning. This is the narrative “progress” of the work. And this is actually when I feel the work is most successful, somehow—when it serves as an occasion to present the desires of others, represented by aspects of the location and its décor, the individuals who perform it, and the cultural regimes that condition these performances.

––Catherine Sullivan, from “Catherine Sullivan Talks About The Chittendens, 2005”; Artforum, February, 2006

On January 5, 1889, Frederick Nietzsche wrote one of his most mysterious and widely interpreted letters to his colleague and admirer, the Swiss historian Jakob Burckhardt, wherein he famously declared that “every name in history is I.” I think of this phrase encountering Chicago-based artist, Catherine Sullivan’s work, which, for me, embodies what Nietzsche may have been getting at through his inspired declaration. For Nietzsche’s point concerns how individual subjects—those who feel and behave in particular ways—relate to larger tendencies and events within narrative History. Events and personages pass “through them,” and the individual actor reacts to these historical moments: that is, one reenacts the “once felt” in order to make feelings active again. This reacting of subjective and intersubjective complexities is compulsory. As a seizure of one’s consciousness and bodily imagination it is the stuff of psychosis (tics, spasms, motor-sensory dislocation, aphasia, bodily resentiment). However it is also the stuff of performance—theater in the most ancient and recent of senses. Theaters of “cruelty” (Artaud) and “hysteria” (Richard Foreman’s Ontological Hysterical Theater).

In Catherine Sullivan’s 2004 work, D-Pattern, developed with composer Sean Griffin, the viewer/audience member encounters a group of actors walking upon a wide staircase on an open stage. The actors immediately appear “weird”—their movements are odd, they seem to be “freaking-out” or possessed. In this work, Sullivan pioneered what has come to be one of her primary techniques as a visual artist both invested in theatrical and cinematic problems. The D-Pattern is a numerical pattern for performance, whereby actors develop a set of gestures repeatable within numeric-serialist patterns. As Sullivan explains of D-Pattern in a statement about her 2005 work, The Chittendens:

In Catherine Sullivan’s 2004 work, D-Pattern, developed with composer Sean Griffin, the viewer/audience member encounters a group of actors walking upon a wide staircase on an open stage. The actors immediately appear “weird”—their movements are odd, they seem to be “freaking-out” or possessed. In this work, Sullivan pioneered what has come to be one of her primary techniques as a visual artist both invested in theatrical and cinematic problems. The D-Pattern is a numerical pattern for performance, whereby actors develop a set of gestures repeatable within numeric-serialist patterns. As Sullivan explains of D-Pattern in a statement about her 2005 work, The Chittendens:

Each performer had fourteen base attitudes and each “set” animated different combinations of the base fourteen. The “key” is a guide for how the attitudes are to be treated throughout the phrases, minimized in dramatic stakes, reduced in physical form, abbreviated in time etc., these treatments of the attitudes could be combined, ultimately giving each attitude countless permutation. The attitudes and sets were given to the performers as a script, the only direction which followed was toward the articulation of the “dynamic range” of the score. Along with the attitudes themselves, most of the performers also generated their own graphic interpretations of the five sets. (Secession, 28)

While D-Pattern may be a means of Brechtian estrangement—a way of getting an audience beyond catharsis and identification with the character’s psychology—it seems more so a means of calling forth the condition every name in history is I as a condition essential to theatricality. By every name in history is I “acting” is reducible to a series of gestures that recall different events (or “attitudes”) in intersubjective histories. The recombination of scored gestures performs the unfinished business of a bodily unconscious conditioned by a complex of social and economic forces, and regimes of discipline and of power.

When I encountered Sullivan’s The Chittendens in the fall of 2005 at Metro Pictures gallery, I was immediately enthralled by what I took to be a case of every name in history is I—a phrase I was thinking about at the time. Seeing this multi-channel installation at Metro Pictures, Sullivan’s use of actors was striking; that these actors were psychotics and, withdrawn from reality as such, experiencing historical events as affectively recurrent, traumatic and unresolved. Through Sullivan’s use of sets (an abandoned office building in Chicago and the ironically named Poverty Island in Wisconsin), and costume (contemporary, early 20th century, and 19th century) I recognized Sullivan to be saying something about the nature of psychotic realities as they concern coeval subjectivities.

In The Chittendens we move among two or more time periods. These periods are negotiated technically through costumes and gestures redolent of a bygone era (teens or 20s judging from the costumes), but also through precise uses of editing and lighting. In the Screen Tests video of The Chittendens, the viewer watches an actor dressed in contemporary costume on the set. As soon as they arrive on the set, the backlighting for the shot disappears leaving the actor in darkness, upon which is superimposed an image of the actor sitting at a table, acting out the same gestures as their counterpart, only in a different costume. As Sullivan herself describes the Screen Tests:

In The Chittendens we move among two or more time periods. These periods are negotiated technically through costumes and gestures redolent of a bygone era (teens or 20s judging from the costumes), but also through precise uses of editing and lighting. In the Screen Tests video of The Chittendens, the viewer watches an actor dressed in contemporary costume on the set. As soon as they arrive on the set, the backlighting for the shot disappears leaving the actor in darkness, upon which is superimposed an image of the actor sitting at a table, acting out the same gestures as their counterpart, only in a different costume. As Sullivan herself describes the Screen Tests:

The Chittendens Screen Tests were filmed in an executive boardroom. These screen tests present one score per actor in different costumes, filmed in two takes, one in black-and-white, the other in color. The takes are then dissolved over one another, so that any inconsistency in the performance between the takes is revealed: The performer either unifies his action over two disparate moments in time, or fails to ‘self possess’ in the boardroom’s high-stakes ambience.” (Artforum, 176) In these scenes, every name in history is I can be perceived as a non-chronological history of traumatic affect, a history which recurs rather than maintaining continuity or sensory-motor synthesis. The actor displays the same gestures, only at different chronological moments indicated by costume. These two times overlap; they are of the same event of “being” or affect, however distanced in time by costume, and lighting.

In Lebanese writer Jalal Toufic’s work, which repeatedly refers to Nietzsche’s correspondence from Turin as well as many of the philosopher’s concepts, the figure of every name in history is I is one which occupies time and space as “labyrinthine.” In Toufic’s “cult classic,” (Vampires): an Uneasy Essay on the Dead in Film, the labyrinthine time-space of the one who declares every name in history is I is embodied by what Toufic calls “ruins.” The ruins of Toufic’s work are actual: the ruins of Sarajevo, of Auschwitz, of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and most of all Beirut—the main site of the Lebanese Civil War and occupations by Israel in the late 70s and early 80s of which Toufic is a survivor. Toufic also discerns ruins “virtually” in any number of films, including Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining:

How provincial 1992 Beirut would be were it not for war and civil-war ruins. Through becoming ruins, some buildings that were landmarks of pre-war Beirut are now its labyrinthine zone. What is site-specific about Lebanon? It is the labyrinthine space-time of its ruins, what undoes the date- and site- specific. […] One can preserve a war-damaged or crumbling building, but no one has any control over whether it will remain a ruin. I am fascinated by how and why war-damaged or crumbling buildings turn from ruins, with their idiosyncratic, often labyrinthine temporality, to that of more or less precisely datable structures in chronological time. [(Vampires), 69-70]

I am reminded of Kubrick’s The Shining watching The Chittendens, insofar as that film also negotiates two (or more) time periods through a specific film location and characters (the Overlook hotel then and now, Jack Torrence and his family then and now). Sullivan herself refers to the primary location of The Chittendens—an abandoned office building—as a site of “bad vibes.” And it is clearly such bad vibes that she is “channeling” through her actors. The office building of The Chittendens is a ruin in Toufic’s sense of this term—a space that one negotiates beyond chronological continuities—and as such is the site of that which transcends time and space, as well as singular historical entities.

Sullivan got the idea of The Chittendens from an insurance logo in Arizona with the image of a lighthouse. For the characters who populate The Chittendens, however, there is no insurance; the actors who enact its drama are victims of the American economy as it is driven by economic competition, and security in the form of an insurance racquet. Between then (teens?) and now (the present?), the characters replay actions and emotions born of the difficulties of a ruthless economy as one actor intones “spare some change” and another invokes the numbers she has presumably crunched for the analysis of an insurance claim. The ruins of The Chittendens are the rubble from which our society has yet to find its way out, and so Sullivan displays the effects of the struggle as a struggle to overcome economic bad conscience in the forms of the bodily and mental traumas insurance industries inflict. The bodily struggle to assimilate an individual and collective imagination of the past which has not ceased to pass.

Sullivan got the idea of The Chittendens from an insurance logo in Arizona with the image of a lighthouse. For the characters who populate The Chittendens, however, there is no insurance; the actors who enact its drama are victims of the American economy as it is driven by economic competition, and security in the form of an insurance racquet. Between then (teens?) and now (the present?), the characters replay actions and emotions born of the difficulties of a ruthless economy as one actor intones “spare some change” and another invokes the numbers she has presumably crunched for the analysis of an insurance claim. The ruins of The Chittendens are the rubble from which our society has yet to find its way out, and so Sullivan displays the effects of the struggle as a struggle to overcome economic bad conscience in the forms of the bodily and mental traumas insurance industries inflict. The bodily struggle to assimilate an individual and collective imagination of the past which has not ceased to pass.

It was like sudden time in a world without time,

This world, this place, the street in which I was,

Without time: as that which is not has no time,

Is not, or is of what there was, is full

Of the silence before the armies, armies without

Either trumpets or drums, the commanders mute, the arms

On the ground, fixed fast in a profound defeat.

––Wallace Stevens, from “Martial Cadenza”

Malice dominates the history of Power and Progress. History is the record of winners. Documents were written by the Masters. But fright is formed by what we see not by what they say.

––Susan Howe, from “THERE ARE NOT LEAVES ENOUGH TO CROWN TO COVER TO CROWN TO COVER”

Triangle of Need continues Sullivan’s investigation of a Capitalist symptomology, as its players are driven by ruthless competition, deceit, and disaster. The elements which comprise the narratives of Triangle include an internet banking scheme, whereby the character Dr. Obi would “reappropriate” the funds of a Harold Bowen and his family who died “tragically” in a car accident (one of those e-mails we periodically get in our junk mail box); a set of orphaned children taken for “Neanderthals” and forced to breed on an estate in Miami; footage of an Olympic hopeful figure-skater; film stock from a bygone distributor; and a synthesis of poems after and including Edgar Allan Poe’s “Eulalie.”

In the three-channel, black-and-white video installation of Triangle, one sees characters gathered at a tenement house in Chicago. Here any number of dramas unfold, including the schemes of a gypsy family who exhibit their comatose daughter, Eulalie; neighbors bickering; a missionary who seems to have designs on Eulalie and her family; and a cast of dancers who dance around Napoleon and his unfaithful wife, Josephine. The scene of mourners gathered around Eulalie takes place in a typically Sullivanesque fashion, as Eulalie is played by three different actors: one a black man, the other a white man, and the third a white woman. The fact that Eulalie is played by actors of various cultural signifiers once again proves Sullivan’s commitment to an identity-bending that plays upon a contemporary logic beyond identity politics. Identities are substitutable among Sullivan’s actors, and this substitutability creates an incommensurable play of difference within our current global economic culture—with the terrain of identity fluctuating in conflict.

In the three-channel, black-and-white video installation of Triangle, one sees characters gathered at a tenement house in Chicago. Here any number of dramas unfold, including the schemes of a gypsy family who exhibit their comatose daughter, Eulalie; neighbors bickering; a missionary who seems to have designs on Eulalie and her family; and a cast of dancers who dance around Napoleon and his unfaithful wife, Josephine. The scene of mourners gathered around Eulalie takes place in a typically Sullivanesque fashion, as Eulalie is played by three different actors: one a black man, the other a white man, and the third a white woman. The fact that Eulalie is played by actors of various cultural signifiers once again proves Sullivan’s commitment to an identity-bending that plays upon a contemporary logic beyond identity politics. Identities are substitutable among Sullivan’s actors, and this substitutability creates an incommensurable play of difference within our current global economic culture—with the terrain of identity fluctuating in conflict.

The figure of Eulalie is a figure of exploitation. Like the orphan Neanderthals who populate the 4-channel, color installation of Triangle, she is asleep, and can therefore not speak articulately for herself. When she wakes, she is replayed by her father, who would continue to exploit her role for profit. In the figure of Eulalie, I am reminded of the Romantic American literary tradition of Edgar Allan Poe. There is something telling, if not uncanny, about Sullivan’s use of the figure of Eulalie in Triangle, as Poe’s poem allegorizes a problem of language itself, and the Romantic nostalgia for “Adamic” language—language “before the fall,” history, relationality.

This problem is commensurable with 19th century European and American industrial economies. Romantic literatures developed as responses to the mobilization of industrial forces, the rapid growth of urban and suburban centers, and the abject conditions of labor in places such as London and New England (Lowell, MA for instance). In lieu of these developments, Romanticism enacts a tension between a desire for return to “the way things were” (longing for antediluvian conditions of “natural production”) and a practical need to address social strife and contradiction (the revolutionary political commitments of a Wordsworth or Shelley come to mind here, as well as Emerson and Thoreau). Transformations of Anglophone poetic language in the 19th century bear-out these tensions through sonic longings—longings for pure music, a language likewise “before the fall” from imagined “grace.”

Eulalie: as in “eukulele,” or “euphony,” or “labia”—the lips which would pronounce a genital, desiring speech. The name rolls off the tongue, it produces pleasant sensations in the mouth when one says it. As in Poe’s more famous onomatopoeia, “bells bells bells bells bells bells bells,” the name “Eulalie,” repeated within the poem and reflected by the poem’s sonorous, “musical” language, embodies a state of language between “pure sound” and disciplinary cultural articulation (acquisition, training). In psychoanalytical speak (Julia Kristeva, Jacques Lacan), the poetics of “Eulalie” is between “the symbolic” and “the imaginary.” It articulates social meaning in relation to that which antecedes meaning as a nostalgic cultural wish for origin and reinstatement. Proto-semantics broaching “pure silence.”

In many of his poems, Wallace Stevens also imagined and embodied usages of language that should preclude social conflict and struggle. A primordial silence before time and space: “This world, this place, the street in which I was, / Without time.” In this endeavor, Stevens reflects Poe’s own desire to compose a poem between pure sound and social utterance. In Stevens’ poem “Martial Cadenza,” he imagines a “silence before the armies.” In contemporary American poet Susan Howe’s telling slant of Stevens’ poem through her own proem, “THERE ARE NOT LEAVES ENOUGH TO CROWN TO COVER TO CROWN TO COVER,” she proposes, oppositely, “For me was no silence before armies.”

In many of his poems, Wallace Stevens also imagined and embodied usages of language that should preclude social conflict and struggle. A primordial silence before time and space: “This world, this place, the street in which I was, / Without time.” In this endeavor, Stevens reflects Poe’s own desire to compose a poem between pure sound and social utterance. In Stevens’ poem “Martial Cadenza,” he imagines a “silence before the armies.” In contemporary American poet Susan Howe’s telling slant of Stevens’ poem through her own proem, “THERE ARE NOT LEAVES ENOUGH TO CROWN TO COVER TO CROWN TO COVER,” she proposes, oppositely, “For me was no silence before armies.”

History is always noisy, it is a language (to paraphrase Stevens elsewhere) that only becomes “muddier” with time, history and the mediations time and history necessitate. That they are gypsies—a diasporic people stereotyped as “shifty” and economically distrustful—who should bear this burden of exploitation in Triangle only complicates Triangle’s noise through winking stereotype. No one is a cause of this noise per se (Sullivan is not after causes), only an effect among effects, what Sullivan recognizes as an “effusion” of meanings. In one of the final scenes of the 3-channel installation, after the nymph-like dance of three players in front of a backdrop of artificial snowfall, someone rolls a heavy, wooden barrel which sounds prominently in the soundtrack. This barrel I take as a signal for exit—Exeunt!—but it is also the noise of history itself, a noisiness which gives principle shape to Triangle of Need.

Throughout Triangle we hear Sullivan’s characters communicate to each other in a made-up language. This language developed by Sean Griffin, one of Sullivan’s collaborators, is a language based on pseudo–scientific theories of “pre-human” language acquisition Griffin calls Mousterian. Hearing Mousterian uttered throughout Triangle, I was originally reminded of Modernist attempts to develop a poetics of “pure utterance” (Italian and Russian Futurists, German Dada, Primitivists). While Griffin would pose Mousterian critically as a language contrived after German Race Theory in the statement he includes in the catalogue to Triangle, it is also poignant as a contemporary instance of an avant gardist wish to develop language uses which should transcend cultural differences while enacting its central burden of historical renewal. As such, this use of language and its connection to a historic avant garde, is yet another level of meditation which Sullivan and her collaborators enact, a side glance at an avant garde’s complicity with the “powers that be.”

At the center of Triangle’s 4-channel color installation are the “orphans” of a supposed “Neanderthal race”—the “last of their kind.” Shot at the Miami estate of agriculturalist James Deering, the Neanderthals are subjected to “breeding experiments.” Through the Neanderthals, Eulalie, and the proto-semantic language of Mousterian, Sullivan brings to the foreground problems of discipline and genealogy as they occur through language. Posed against the Neanderthals are the nefarious schemes of their captors—agents of the academy, religious wisdom and the state alike—who would like to both study the Neanderthals, and continue their existence albeit through processes of “civilization.”

As one considers these experiments in relation to historical social experiments—those at the Nazi concentration camps and of various American eugenic research projects, for two such examples—the stakes of Sullivan’s project are raised. Competing are two groups that would like to subsist, yet one through competition (“need” so called), the other through something else. This distinction between “need” and an alternative to need is articulated in a scene of the four-channel installation where one sees the orphan-Neanderthals conferencing about whether they should continue their race. The Neanderthals recognize they are of “desire,” and so would oppose the “need” of their captors as a drive towards social competition, success, and unpropitious domination. It is telling of a larger cultural dilemma, that the ultimate decision of their conference is to discontinue their race.

While Triangle of Need incorporates historical documents, these materials originate in pseudo-histories, realities that are part of history. They are factual and real, and yet incidental to the master narratives. Such is the case of the document which gave inspiration to Triangle’s primary narrative thread—the junk mail letter from Dr. Obi; as well as the Deering mansion, which would seem not unlike the Xanadu of Orson Wells’s Citizen Cane, or the estates of our current billionaires and superstars. While these places exist in the “real world,” they also exceed history—like Disneyland exceeds history, or the Trade Towers once seemed to.

While Triangle of Need incorporates historical documents, these materials originate in pseudo-histories, realities that are part of history. They are factual and real, and yet incidental to the master narratives. Such is the case of the document which gave inspiration to Triangle’s primary narrative thread—the junk mail letter from Dr. Obi; as well as the Deering mansion, which would seem not unlike the Xanadu of Orson Wells’s Citizen Cane, or the estates of our current billionaires and superstars. While these places exist in the “real world,” they also exceed history—like Disneyland exceeds history, or the Trade Towers once seemed to.

As one makes their way from the four-channel installation at Metro Pictures they encounter the final room of Triangle’s three-part installation. Here we see grainy 8mm footage of a woman, seemingly on her wedding day. Could this be Eulalie? The footage appears taken in a foreign and tropical place (the Deering mansion in Miami?). The graininess and hand-held feel of the footage provides the viewer with something warm, and yet distant. The footage has the feeling of being shot in the past, a past we might like to travel to. The footage of this woman on her wedding day is, in other words, nostalgic. There is something soothing about this footage, however disturbing in concert with the videos we have just watched.

Mixed with this is black-and-white film 16mm footage of a figure skater. The camera tracks around a skating rink, and then zooms on the skater, as he performs twirls, spins repeatedly. Close-ups of the figure skater reveal his musculature and long hair. When I spoke with Sullivan at her opening, she told me she had asked the skater to perform these twirls for their dramatic effect. While the moves of the figure-skater are graceful and hypnotizing, the skater himself is an ironic kernel around which the rest of Triangle’s works move (triangulated?). For the skater is the element of kitsch that Sullivan’s works always risks including: “Adding additional infromation is in a sense forcing the viewer away from the reductive and mutually congratualatory aspects of the kitsch experience of reference. For me kitsch is only offensive when its function is to affirm a nostalgia for the original thing or a pedigree necessary to its recognition. I think the end result bears some anxiety about this question, the specter of kitsch looms over every work of mine…” (Secession, 24) As such the skater is a figure of abjection and pathos. The “real story” behind Sullivan’s employment of the skater, Rohene Ward, is that she “found” him in Minnesota working for certain ice shows (akin to “The Ice Capades”), and was hard-up for money, though he was once an Olympic hopeful, and is listed as such in Sullivan’s character description from the Walker catalogue for Triangle.

This tongue-and–cheek inclusion (not at all apparent from the footage of the skater himself, or anything in the Walker catalogue) reminds me that in Sullivan’s art, questions of burning ethical and political importance are necessarily being approached through the sidedoor. Through what is minor, pseudo-historical, if not mythopoetic and/or entirely “made-up”. This ability to play effectively, effusively, between the real and the imaginary, History (with a capital “H”) and history’s “bit-parts,” may finally be the most important contribution of Sullivan’s art, and her latest and most elaborate work to date.

Works Cited:

Artforum February, 2006. “Catherine Sullivan Talks About The Chittendens, 2005.” ed. Tim Griffin.

Klossowski, Pierre. Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle. London/NYC: Continuum, 2005.

Sullivan, Catherine. Secession 7.7.-4.9 2005. London, Tate Modern/Secession, 2005.

Toufic, Jalal. (Vampires): an Uneasy Essay on the Undead in Film (2nd ed.). Sausalito: Post-Apollo press, 2003.

All images courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures.