Empathy and Resistance: An Interview with Alan Michael Parker

06.08.18

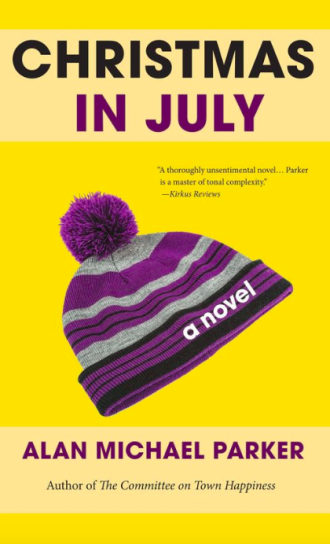

Poet, novelist, and essayist Alan Michael Parker’s latest book Christmas in July (Dzanc Books) tracks the journey of a runaway teenager who’s named herself Christmas and suffers from terminal cancer.

Poet, novelist, and essayist Alan Michael Parker’s latest book Christmas in July (Dzanc Books) tracks the journey of a runaway teenager who’s named herself Christmas and suffers from terminal cancer.

It’s an intimate and deeply emotional story, but instead of being narrated by Christmas herself, it’s told from the perspective of the townspeople who encounter her over the course of a single month.

The result is a kaleidoscopic tale that maps life in a small town and the final weeks of a dying girl, without ever veering into sentimentality.

Simultaneously a novel and a collection of stories, Christmas in July slyly upends narrative conventions and asks readers to inhabit the minds of a wide variety of characters.

I spoke with Alan Michael Parker via email about the artistic and political ramifications of his remarkable book.

JEFF JACKSON: One of the most remarkable things about Christmas in July is how the story of the sick teenager Christmas is narrated by ten different characters, each of them relating their encounters with her in the first person. Why drew you to this approach and these particular narrators?

ALAN MICHAEL PARKER: I’m trying to try stuff: I hadn’t written a novel in the first person singular before, and that seemed to me a cool challenge. And then, when I started writing Christmas in July, I realized almost immediately that the intersection of numerous narrators generated a notion of “truth” worth exploring. That idea drew me to the ten voices—a kind of choral rendering as well (in the civic sense, borrowed from the Greeks). So I think of the novel as a Venn Diagram starring various narrators.

As for the particular narrators, I knew pretty early a few of the voices I wanted to hear (Sarah, Marcus, Snow Joe, Evie Glitter), and then came upon a couple of others while doing “deep Googling” (Dorothy, Aunt Nikki) related to their professions.

Ultimately, the challenge of writing Christmas in July seemed to me the problem of empathy: how and why would each of my ten narrators offer different ways to empathize with Christmas. With the reader in mind, I began to believe that a bevy of narrators might offer us choices—who Christmas might be in each story, and how she touches each of these people, but also who she is as the sum of her interactions.

The book seems to center around empathy on so many levels. There are the ways that both readers and the narrators might empathize with Christmas – but you’re also inviting us to empathize with these narrators. And then there’s how empathy is enacted in the writing itself. How difficult was it for you to inhabit the voices of these wildly different narrators?

You know how a sentence is a kind of thinking, and as it comes out, sometimes it thinks new ideas? And then, how we think again (or right then) differently as a result of the sentence, and so the sentence we speak (say) changes what we think?

Okay, I’ll step away from Gertrude Stein, and the deep structures argument, and try another approach….

I did a lot of “writing aloud,” which to people nearby sounds like muttering. I believe in the mouth-ear as an editor, and when writing in a voice, I try to let the mouth-ear participate editorially.

The hard part: I think just like I think, and the sentences I write default to structures that require resistance. For example, I like colons early: but who among my characters would fashion a thought this way? No one, as it turns out: the early colon becomes a syntactical habit that requires conscious resistance.

The narrators’ language – and also their lives – feels individuated and fully inhabited. It’s especially impressive since these narrators cover a range of ages, genders, social backgrounds, ethnicities, and sexual preferences. With so much talk about appropriation lately, I’ve had several writer friends tell me that they feel like they don’t have the right to write from the perspective of characters who have different races and genders than them. You’ve taken the opposite approach here. What are some of the risks, responsibilities, and rewards that come with writing characters who are different from you?

I remain committed to the imagination as an act of love, and how without claiming knowledge of the Other’s life, especially across racial and sociological differences, we must try. While neither empirical nor objective, fiction offers us truths: my goal in writing from so many P.O.V.s who aren’t mine is to make available these truths. Yes, it’s politically motivated—in this awful time of meanness, and what I call the Age of Inflammation—but it’s also the novel my characters “live” in. I as a novelist needed to allow them space, as Calvino writes in Invisible Cities: “[to] seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.”

The risks: I’m wrong.

More risks: I’m presumptuous or imperious or mansplaining.

And yes, I’m trying anyway. Resist.

Christmas in July might be described as a novel in stories. Your previous book The Committee on Town Happiness was a novel in flash fictions. What’s driven your interest in exploring hybrid – or at least unconventional – forms of the novel? Is it related to your desire to create the space for your characters to exist?

I’m fascinated by the forms a novel might take, and how those forms complicate our understanding of the work’s content; in this sense, yes, whether the novel-in-stories includes onstage action or off-, or manages to link one character’s timeline with another, matters to who we think those characters are, ultimately. But a novel in stories also accommodates the mise en abyme gestures that I have learned from writing poetry—the recursive moments—without sacrificing “readability.” In other words, I can mirror more in a novel-in-stories, because the movement isn’t exclusively propulsive but recursive, too.

I love that moment when in Chapter 7 you remember something from Chapter 2, and draw a parallel regardless of the fact that you’re connecting two different life stories. For me, that’s what the novel-in-stories affords.

Of course, all of the above is provisional—by which I mean that each novel’s form is site specific. We’ll see what my next novel does, formally, and what circumlocutions I generate then to rationalize its behaviors, ex post novelo (see: made up Latin phrases).

There’s an interesting tension throughout most of the stories between what’s in the foreground (the narrator’s story) and the background (the continuing progress of Christmas’s story). As the book went along, I found myself increasingly drawn to the background, sifting the descriptions for signs of Christmas. Where did you ideally want the reader’s attention focused? How actively were you working to direct us?

I’ve long been fascinated by that subject/ground tension in visual art, and was working hard to move my reader to look for Christmas. Early in the writing of the book, I discovered how tempting it was to have her arrive to resolve each narrative—a kind of Christmas ex machina move—which began to feel a bit easy. So, instead, I played with where she would be in each of the ten stories, especially in “Dear Dorothy” and “Glitter.” In the former, are Christmas and Dorothy corresponding throughout? The plot turns on that question. And in the latter, who’s Evie’s ghost? I’m hoping that the reader wants Christmas to be central to each narrator’s “problematic” (as the lit crit Sophists would have it), and that looking for her becomes a desire.

In turn, if we want to see Christmas, our investment in her changes—no spoilers here, the cover copy tells you she’s dying—and what we feel deepens. It’s a move on my part, with the goal of circumventing the sentimentality of the dying child’s story, and focusing instead on our own relationship to this character.