Brandon Brown is Arcimboldo! A Review of THE FOUR SEASONS

07.08.18

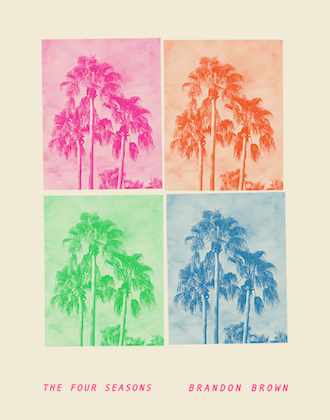

THE FOUR SEASONS

THE FOUR SEASONS

by Brandon Brown

Wonder Books

154 pp

It occurs to me that when I look at the seasons change and think about the seasons I am looking for a myth to live by. A better myth than the available ones.

At first glance this does look like a day book, a packed, overflowing, omnibus of casual, event-driven observation and recollection and reflection and reaction. It is a big book, at over 150 pages, for all of these apparent quotidian jottings are served up to us in Brandon Brown’s now-familiar flowing, inclusive, discursive, conversational, confiding, slightly self-mocking tone. We hear this person talking to us. He’s telling what seems at first to be a story. It is story, a kind of story, and the stories pile up.

But these stories are organized, that’s clear from the start: the book is titled The Four Seasons, and it is organized into four sections, one for each season, starting with Summer. And it seems at first glance, that the poet has just lived a year of his life and is now sharing it with us.

Easeful Summer, where we start. Where, perhaps, we are most at home? ‘Summer afternoon,’ for Henry James, were the two most beautiful words in the English language, as Brown reminds us more than once. What is Summer made of? For this poet in the Bay Area (and this book is rooted in the Bay Area) it is a lazy picnic at the Don Castro, a dip in the river between each course. It is made up of:

kale, grapes, internet wars, water of the Yuba, medical cheeba, Gregg Araki movies, the smell of Alli’s neck and clavicles, a disintegrating leather couch on which I chill, Carly Rae Jepsen…

And then comes Autumn, and the intimations of what will follow, and John Keats arrives, poor doomed Keats. Autumn is stubble fields. It is the season when “the sky turns asphalt, then eggplant.” It’s the time for the Fall Classic and this year, when the Royals win the World Series, the author’s thoughts turn naturally to Royals’ greats from the past:

Dan and I became friends. He would come to “Latte Land” and sit at the counter. I’d make him free pumpkin lattes and we would talk about poetry. I would say like, “have you read Sylvia Plath?” He would smile and say “no, should I?” Just after I moved to San Francisco, Dan was diagnosed with brain cancer and died three weeks later. He was only 45. I was too young to understand how young he was. I wrote a poem for him. The only line I remember is “Dan Quisenberry is dead who should not be!” Exclamation point, all that. I still feel it.

And then we are in Winter, the season of the dead, where the poet goes and visits the dead. The land of the dead looks like the nicer bits of Oakland. John Ritter and Bernie Mac are there to serve as guides. It is a place where you see all of your old friends, who never really left and everyone is there, just hanging out, “like Billie Holliday talking to John Wieners who looked star struck and happy.” Like Dante, just like Dante, guided through the nether-lands, eventually he comes to a place where he is able to see what comes next:

In the land of the dead, actual panthers passed around a Caviar Cone, couch-locked, growl-laughing and coughing sweet clouds of strawberry milk settling over the foggy steppes. We all put our hands in our pockets, whistling as we walked down the slope of winter mountain until, finally, we could see Spring in the distance.

So we have arrived, thankfully, gratefully, at Spring, the season of lust and revolution. The poet steps back, he can take stock, a year has passed. He can report:

Right now nothing is wrong with me. My teeth feel great, I’m not depressed, my knees don’t hurt. My ass doesn’t itch. It makes me feel self-congratulatory, so I reward myself for my excellent constitution by bumming a cigarette.

It’s a Parliament, one of the only cigarettes I almost hate smoking, but I devour it greedily into the air. But, I tell myself later, at least I don’t smoke Oxycontin

And now, finally, now that we’ve gone through the entire year it finally becomes clear, this not a day book, this book is made up of odes. Odes for our time.

Keats did something great and important almost exactly two hundred years ago. Keats, the youngest of the great Romantics took the ode and blew it up. He took that stuffy, empty form that those right-wing shills like Pope had used to puff up those who they wanted to flatter, and he turned into what was seen, immediately seen, as a stripped and brutally honest meditation: this is what Autumn is really about… mortality, encroaching and approaching. This is what this bit of painted pottery tells us… about what he called beauty and truth, and immortality.

But what kind of odes are these? The poet is seeking himself. He is looking for himself. He is looking to understand himself and create his own myth, and by finding, or conjuring up or summoning from afar, or perhaps, and perhaps it always comes to this, confecting himself, from within himself, coming up with some possible answers to questions like: why I am here, still here? Why are we all here? But how does he do it?

Guiseppe Arcimboldo is mentioned several times in this book, the Renaissance court painter best known for his portraits, his sitters’ faces fashioned entirely of congealations of fruits and vegetables, flowers, fish, and books too. They are as startling now as when they were first painted, four hundred years ago. What Brown has done here is quite similar: he’s built up a series of portraits of himself, of our times, by composing a seemingly spur-of-the-moment assemblage which are in fact packed with moment, with pathos and pain, joy and humor. It is as if Arcimboldo executed a series of self-portraits. This is who he is, what he is made of. This is what made him who he is. The likeness is uncanny. A new definition for the term ‘life-like.’ This is what he is the sum of.

In the final respect, we are left with the poet entire, struggling, as he should, as he has to, as do we all if we wish to count ourselves among the witting, struggling to understand who he is, why he’s here, what he’s supposed to be doing while he’s here. He is struggling mightily – his rueful admissions and unashamed confessions attest to that: what does it mean to be a poet today? What does it mean to be a man, in this day and age? What does it mean to live in this country, here and now? He doesn’t have answers to all the questions he poses, and he need not. Nor may we. Being reminded of these questions is perhaps enough, because these are our struggles too. That is why we need to read this book.