Eden Comes Easily to Mind: Nine Questions with Visual Poet Catherine Bresner

16.07.18

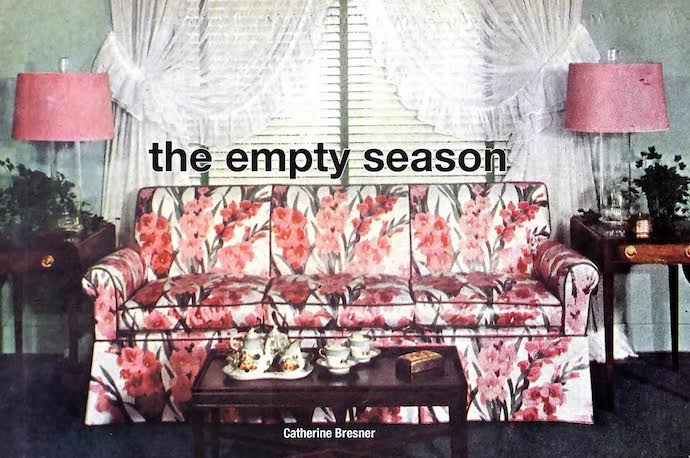

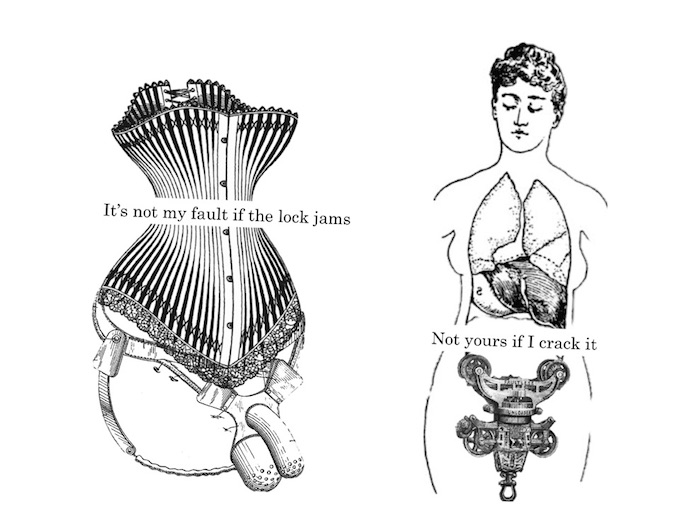

It’s rare to cross a book that is both unclassifiable and compulsively readable, but here, Catherine Bresner’s the empty season, a hybrid poetry collection focused on poetry comics, helps save the book object from wilting into obscurity. Pigeonhole nothing: the empty season is a uniquely formatted collection, designed to give special real estate to its visual punctuation—haunting public domain images and immersive collage works harmonized to summon powers of body horror and feminism, while not exclusively working within genre tropes of comics or poetry. The book expands the breadth of both audiences, unsatisfied with the confines of the page, assumed traditions, and tyrannical hierarchies. In the empty season, Bresner has created a movement, establishing the poetry comic as bookworthy and unrestricted to web ephemera or high art.

The following conversation was compiled via email. – JT

Jason Teal: the empty season is grounded in realism, yet there seems to be a pessimistic (sometimes comedic) politics working throughout. Take, for example, these lines from “4 AM Mind,” which document anxious morning routines:

To believe in a thing is to nurse

a small baby in the brain until that

baby grows up to resent you for living

the way you do. Still, what a comfort

to believe in jesus, for instance, caspering

around our houses, nudging our tender elbows

off the table.

The poem pokes fun at ideologues, but also presents a grim portrait for those of us who have been told “be calm,” that our tragedy is part of “the master plan.” Within the book, we sense frustrations of each speaker mounting into one unstoppable chorus. I wonder if you see these same interstitial relationships forming in your book, and how did you decide on the title poem being representative of the collection?

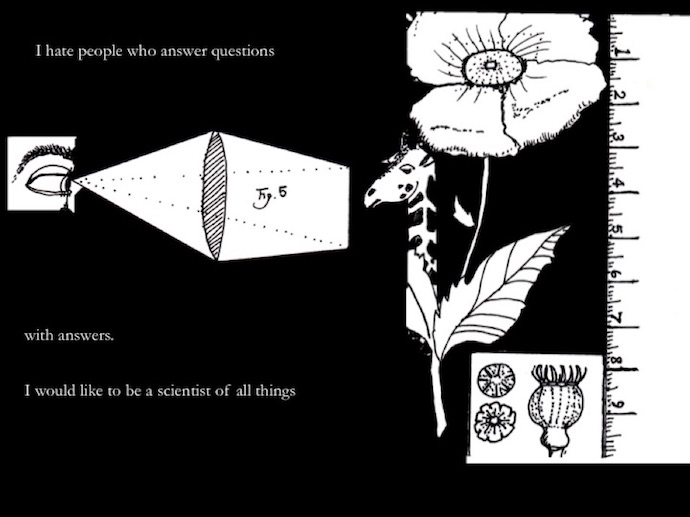

Catherine Bresner: I am very suspect of ego, and I think the reason why I put pressure on power systems, whether they be religious, gendered, or racial, is because I have a deep anxiety about my own complicity. I grew up in a fairly religious household, and from a young age, and I had a deep fear of being judged. When I was young, I would parrot the adults in the room, because I didn’t have an honest vocabulary to articulate my experience. Platitudes like “Everything happens for a reason” or “Time heals all wounds” or “What doesn’t kill us makes us stronger” seemed like cheap, frothy emotional appeal that was a cold comfort when I witnessed real tragedy. It takes a big ego to say such phrases to others because it assumes an impossible knowledge on the part of the speaker. I think that is why I write poetry. When poetry is very good, its logic resists singular or binary thinking, and it lives in a gray, dreamlike logic that feels authentic. I think the title poetry comic speaks to this frustration a lot:

I like to think of the culmination of the poems as a literary bitch slap to know-it-alls. Have you ever carried on a conversation with one of these types of people? It is very boring. What is attractive about poetry comics is that the form is a mysterious as the language of poetry. While this title poem is illustrated, digital collage seems well suited for the poems that I write now. Just as I didn’t create language as a medium for poems, I didn’t create the images I collage, either. I like the way this nebulous form lives in a place of instability, evocation, and conundrum.

The poem “the empty season” was the very first poetry comic that I did, and it only seemed natural that it be the title of the book for many reasons. Originally, the book was going to be titled Take Off Your Wooden Overcoat, which I was married to for a long time. The first time I ever heard the term “wooden overcoat” it was in Rick Barot’s gorgeous poem. I loved the image of a coffin being a wooden overcoat, and because I am always trying to experiment with nonpoetic forms (Wikipedia entries, comics, sentence diagrams), I thought that this would be the perfect metaphor for shrugging off old ways of doing things. In the end, I realized that Rick Barot’s poem did more justice to the image than my book title did, and so I abandoned it. It now seems that this book was always meant to be titled the empty season, as it is not only a marker of the present political moment but because it occupies a nebulous time in my life personally. Seasons usually mark times of change, but in this book the poem seem to point to a sadness that feels timeless.

This approach to creating poetry with a specific audience in mind seems to increase the vibrancy of the collection. In the Wikipedia poem “To Know a Thing,” we are soliciting a fuller range of humanness “terrorized by human / frailty.” You leave a trail of indirect citations about that the reader might access but may also choose not to. This technique seems like a funny way to posit relationships.

I’ve worked with educators who encourage worlds outside of poems, yet here you are, eschewing a references list or footnotes, exposing the gadgetry of the poem for the reader, who, initially, might only snicker but never think twice about the webpages—missing connections to collage makers, dead illusionists, family courtroom dramas, etc. Going along these lines, I wonder how did you arrive at making poetry comics, and when did the decision to pair this with experimentally formed yet more typical page poetics result?

When you say creating poetry with a specific audience in mind, it makes me think of the book I am reading right now by the poet Joshua Beckman, Three Talks. He writes, “For me the endeavor of the poems is greater than the poems – or endeavor of poetry is poetry…. the magic of the poems seems to be an amazing coexistence of all these states – social – collaborative – and shared – before and during its making – constructed and formalized as it is being read, etc. – I imagine it as an interpersonal state, like friendship.” I think when I was a younger poet, I wrote with a very specific audience in mind. But these days it is not so specific. I am very grateful for the generosity of readers (like yourself) that take the time and enjoy reading my poems, and each poem in the empty season came from a very mysterious “interpersonal state” that is sometimes quiet and wistful and other times fidgety, irritable, or grieving. Moods and dreams are more honest compass points for me than audience or projects. I have always admired poets who can skillfully craft a book with a specific idea in mind or a message to convey; it is a very hard thing to do without coming across didactic. The meaning-making part around the creation process naturally comes for me during rewrites and editing, when I am noticing nodes within poems. When I go into a poem with a very specific audience or message in mind, I can’t surprise anyone, least of all myself.

With the Wikipedia poem specifically, I like giving readers a choice to engage with it as they wish (PSA: Wiki hole > K hole). The form lends itself to a curious reader in a way that feels honest to me, as someone who was born into the age of analogue and was educated in the digital age. I wrote that poem after W. H. Bush’s presidency—but before Trump’s, which I think already makes it part of a historical conversation that is still germane to the present moment, where Tweets are shoddy substitutions for facts. And information in the digital age is like this, is suspect, but also wildly entertaining. So I don’t think in order to enjoy or understand “To Know a Thing” a reader has to engage with the Wiki pages, but if they do, it should be fun. The links are a stand-in for a level of associative thinking and assumptions that we bring to anything we read.

And I think this last point speaks to your question about pairing poetry comics with page poems. I wanted the reader to be surprised/delighted/haunted by their presence, because, initially, they seem like a disruption. But rather than a disruption, their presence is fundamental to some of the book’s obsessions: What is poetry? and Who gets to decide what it is? We come to the page with all sorts of notions about how poetry is supposed to look, feel, and gesture towards. The poems I like to read don’t just echo a familiar experience; they operate in a state of negative capability that leaves me dizzy with wonder.

I didn’t even know what a poetry comic was until I met the poet Bianca Stone. She was stretched out on the floor of Flying Object, an artist space that used to feel like home to me in Western Massachusetts, with her watercolors and letters working on a project. I sat down next to her and asked what she was working on. I can’t remember if she used the term “poetry comics” then, but I was curious. Her pen + ink + watercolor + poetry terrified me in a way that the best poetry does. I didn’t know that poetry could do that, didn’t know about the work of Joe Brainard, Sophie Poldoski, and Kenneth Patchen yet.

You said earlier that you did not create many images you used for the poetry comics, using instead digital collage alongside illustration design to build the pieces (and later book acknowledgements are made for borrowed images). However, much of the included images seems to evoke grotesque captures of behavior, thinking back to “Election Year,” “January 2nd,” and “Bond Voyage,” creating white noise of missing features, law enforcement tools, kinky spankings, hybrid beasts, dissection/vivisection diagrams, to name a few. How rigorously did you have to vet some of the images you found, and did you ever create words prior to researching images?

I am just as choosy with images as I am with words. I think of them as just another medium to work with, and like other mediums (paint! clay! playdough! glitter!) words and images are messy. But I love the mess. Figuratively, the messy interplay between poetry and images provides a deeper understanding of the poem as a whole while simultaneously complicating a first reading. With “Election Year” and “January 2nd” I scoured the internet for source images that were in public domain with an idea in mind. Each poem has a discrete aesthetic (“Election Year” images come from Victorian illustrations and sexist ads from the 1950s primarily and “January 2nd” images come from 60s pulp novels and 70s beauty magazines), which helped narrow the searches. With “January 2nd” I had already created the poem, so finding images that texturized the reading was very fun. The process for “Election Year” was quite a bit harder because I started the poem, then began creating images, and then continued to write the poem around the images. I would come across an image and the poem line would write itself. But I feared that this way of creating would be too obvious, the text informing the image this way, so I made a personal rule to alternate each panel. On one, I would create the poem line and then find the image, then reverse the process. It was tedious, but in the end, it balanced out.

I am just as choosy with images as I am with words. I think of them as just another medium to work with, and like other mediums (paint! clay! playdough! glitter!) words and images are messy. But I love the mess. Figuratively, the messy interplay between poetry and images provides a deeper understanding of the poem as a whole while simultaneously complicating a first reading. With “Election Year” and “January 2nd” I scoured the internet for source images that were in public domain with an idea in mind. Each poem has a discrete aesthetic (“Election Year” images come from Victorian illustrations and sexist ads from the 1950s primarily and “January 2nd” images come from 60s pulp novels and 70s beauty magazines), which helped narrow the searches. With “January 2nd” I had already created the poem, so finding images that texturized the reading was very fun. The process for “Election Year” was quite a bit harder because I started the poem, then began creating images, and then continued to write the poem around the images. I would come across an image and the poem line would write itself. But I feared that this way of creating would be too obvious, the text informing the image this way, so I made a personal rule to alternate each panel. On one, I would create the poem line and then find the image, then reverse the process. It was tedious, but in the end, it balanced out.

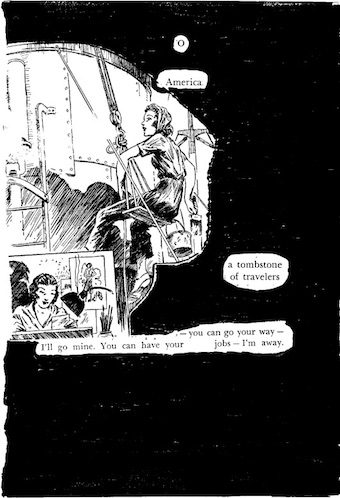

Literally, creating these comics can be messy, too. For “Bond Voyage,” I used the source text Vagabond Voyager (A horrible read, by the way. I don’t recommend it) and I cut words, erased words with Bic without, blacked them out with sharpie, glued illustrations that were already in the text.

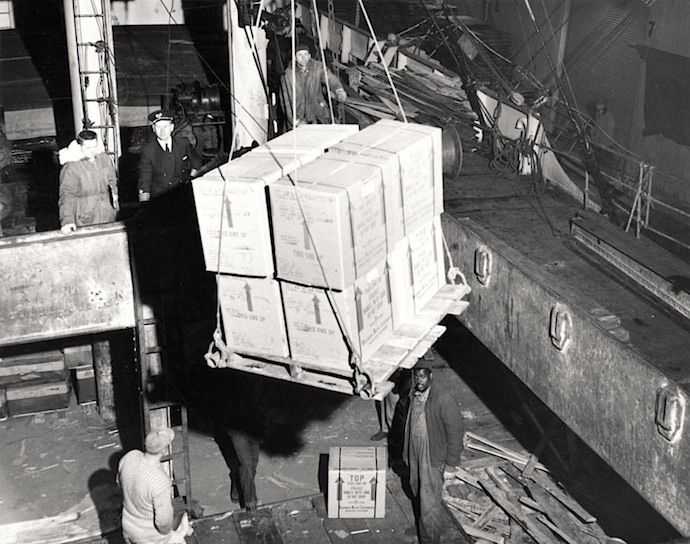

The final image of this poem, was truly a piece of found art—unlike the rest, which was summoned by either Google or illustrations from the book the poem came from. I stumbled across it on a website about the Milwaukee shipping industry while researching a different project. The image seemed unsettling to me in so many ways: it is hard to discern what the cargo is, there is a man stepping from the shadows, the white captain and crewmen are much higher on a scaffolding above the black dockworker. All of it pieced together a disturbing narrative that spoke to the violence of the poem and its source text.

Is there any medium you won’t mess with? Or, to rephrase, is there a medium you think poetry comics can’t experiment with?

I want to believe that if treated with extreme care, there are no limits to the hybridity of poetry. I want to believe that. But even in my experimentations, I have found that when I try to fit poetry into a medium that doesn’t make sense, the poem fails. I have thought about creating poetry memes, for instance. What would that look like? How would a poem speak or respond to that particular digital medium? I have no idea. But my gut tells me that the meme medium would make it look like a gimmick or silly in the worst way (and not silly in the best way), but perhaps that has to do with more of a shortcoming on my part than the part of the medium.

A press that really excites me right now is Container because it is very concerned with medium. This press creates poetry objects (or objects that contain poetry) that push against our ideas of readership and the traditional book form. The press’s mission is as hard to define as it is to contain, which is exciting in the same way that poetry is exciting—its ability to speak to that which is ineffable.

Staying with incorporated imagery, there seems to be an embedded motif of sheep and Ovis-fueled characterizations across poems, which have symbolic correlations with self-sacrifice and community. Is there a motivating factor for using some animals above others? There are hummingbirds, horses, cats, crows, and even chimeras throughout the book, for example, but few snakes or reptiles.

I love sheep, goats, crows. I like the poetic history they keep (I am thinking of Bridgid Pageen Kelly’s “Song” in particular.) And I love chimeras because they most accurately reflect the human form. I don’t know why I don’t have reptilians in the empty season, except that they are not part of my everyday landscape. In Seattle, every night the crows migrate at dusk. You can hear them and see them, if you are paying attention. It is a strange and beautiful thing to witness. I don’t know where they go, but there they go … every night. I like taking walks in the early evening in my neighborhood, and I always hear them in the trees. But I don’t have a hierarchy of animals—maybe I will use a snake. Although, snakes are especially tricky because they are so symbolically laden. It like putting an apple in a poem. Eden comes easily to mind.

I want to ask you about the poem “For the Well-Intentioned People Who Say Writing Is Therapeutic.” What inspired this poem in particular? I sense some history or a prompt. I’m also curious about your relationship with writing poems and how it has changed since publishing the manuscript. Has it?

That poem definitely came from the gut. While I was writing this book, I was going through a brutal divorce after a twelve-year relationship, and luckily I was seeing a very good therapist. However, even the best therapists are just humans, which means that they can only empathize, never sympathize. With a very kind heart, she encouraged me to “write through the pain,” and I wanted to throw up. Not just because it seemed like cold comfort for the tremendous grief that I was experiencing, but because it seemed to be antithetical to what I think the purpose of poetry is for me. In my experience, poetry can provide solace in the reading or hearing, but not in the writing. I can’t write a good break-up poem in the middle of a break-up. I can’t write a poem dealing with death while dealing with death. I am too in it to feel it, if that makes any sense. It is only later, upon reflection, can I make sense of such things. The “fuck you” isn’t just necessarily to my therapist or other “well-intentioned” folks, but a finger pointing back at me, similar to the move that Elizabeth Bishop makes in “The Art of Losing”: WRITE IT—

My poems have changed a lot since I finished the empty season (as I wrote many of the poems three to four years ago). When I wrote the fuck-you poem, I was rereading Anthony McCann’s I ♥ Your Fate, which has this fantastic rhythm to it. The poems in his book were a springboard for the cadence that I employed in “For the Well-Intentioned People …” I still like experimenting with invented forms and creating poetry comics, sure, but my poems have gotten a bit more sonic and a bit less visual. Often, I chew on a rhythm in my head for a few hours; I can hear how the words would sound before I even know what they will say, before writing anything down. I have been reading poems aloud alone more, which is something that I did all the time growing up, but that I got away from in grad school.

Besides pain and death, what abstracts can’t poetry also contain?

I am not sure if poetry can really contain any abstracts, truly. I think poetry begins in the particular and shoots straight from the hip. We only think about poetry “standing in” for an abstract when we are trying to decode it, which is the very worst way to truly understand it. When I read a poem aloud, before I really understand the words, I understand it sonically. The words are soothing or dissonant, and this makes sense on a corporeal level that I can’t articulate. When Tyehimba Jess writes, “My God is the living God,” he means just that. It isn’t abstract.

the empty season won the 2017 Diode Editions Book Contest. Can you speak to your experience shopping around the manuscript and how you came to know you had a full book on your hands, let alone one of hybrid, visual poetry? Now that you have published a full-length book, are there plans to develop more art down the road, such as graphic narratives?

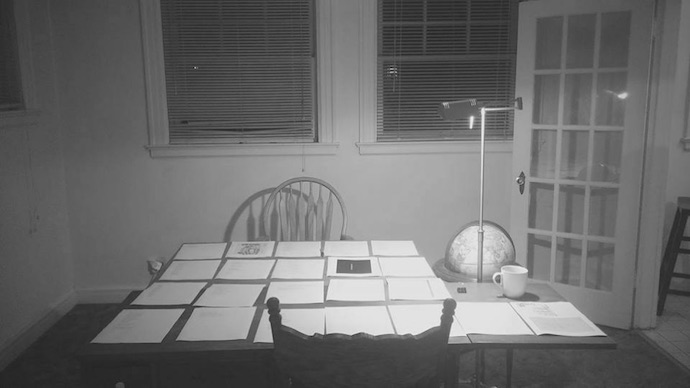

I knew I had a full book on my hands once I had laid it all out on my kitchen table. A poet friend came over, and we pored through the pages, removing some poems, adding others. It was such a wonderful day. When he left, he poked his head out of the car and said, “Congratulations on your book.” I kept it on the table for about a week and just looked over the poems. After a week of looking at it untouched, I decided it was really ready. It was then that I started submitting, and I submitted at least once a week for about a year. I only submitted to presses that I loved very dearly, and I saved my tip money from waitressing to pay for the fees. Worth every penny. Diode is such a wonderful press that is publishing very innovative and daring work; when I had found out that they had chosen my manuscript, I was over-the-moon!

These days, I don’t like to write with a project in mind, but I am creating a lot (a book-length poetry comic, a collection of sentence diagrams poems, and some prose poems), without any expectation of placing them anywhere. Once the glowiness of my book launch subdued, I found that I needed a self-imposed writing retreat, so I took Memorial Day weekend off of social media and cleared hangout plans. I just spent the whole weekend reading, walking through this city I love, and writing. It is a privilege that not many people have—to pause life for a weekend—and I was really grateful for it. I think I was so excited that my book got published, that I got lost in a bit of social anxiety for a while, which I hear is not uncommon for someone coming out with a first book. One of my mentors reminded me very gently that I flip that anxiety into joy. The first part of the process begins in the intense solitude of writing and making, and the publication part of the process is about the mechanisms needed to bring the work to others. This is the kind of thing that Beckman speaks to as well. Whether I am writing or publishing, I am earnestly trying to connect with something greater than myself. So, while I don’t have any advice to myself writing a first book (I took risks! I had fun! I wrote bad poems and then wrote good ones!), I would advise myself during the publishing process to take more time in the company of friends and poems.

You live in Seattle, known for grunge music and live theater, post-hardcore rockers The Blood Brothers, records by Sub Pop, Wave Poetry Books, and Fantagraphics comics—a city where bands are often asked to describe their sound. How would you describe your poetry sound?

I am going to answer the most honest way I can: my answer is in my poem “DSM-V.” In the poem, there is section called “Risk Factors,” and it has part of the music from “Opus 67” from Peter and the Wolf:

I am pretty sure this sheet music is for the piano (why oh why did I not learn the vocabulary for music beyond the recorder?!), but when I see it, I think of the bassoon. It is an odd kind of instrument in my opinion, half playful, half sorrowful with its husky notes. It is not as jazzy as a saxophone or as poetic as a violin. In the story, the bassoon is the “voice” of the grandfather, grumpy and grumbling. I always identified with the grandfather bassoon: What if Peter hadn’t caught the wolf? By the way, Bowie narrating Peter and the Wolf is I think the best way to experience this music. If you haven’t listened to it, here you go.