Diary of a Nobody at Art Basel 38

09.07.07

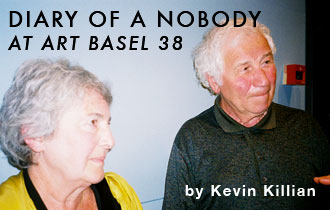

By chance I—a provincial clerk and part-time lecturer—found myself invited to Art Basel 38 in June 2007, the grand fair they call the Olympic Games of the art world. Sporting a gray badge that proclaimed me a “Special VIP” (a badge that, in the course of events, proved markedly less effective than a black, plain “VIP” badge with no “special” status), I found myself passing through turnstiles, caressing the pink silken curves of Tracey Emin’s neon sculpture at White Cube’s booth, laughing merrily, then squinting grimly as if involuntarily recalling the privations of Soviet times, with Emilia and Ilya Kabakov. Through the velvet ropes I swanned like a pro; but inside I was faking it. A nonentity, I had never been to Europe and had reached middle age without even thinking about it, like the 90 percent of my fellow Americans who don’t even have a passport.

By chance I—a provincial clerk and part-time lecturer—found myself invited to Art Basel 38 in June 2007, the grand fair they call the Olympic Games of the art world. Sporting a gray badge that proclaimed me a “Special VIP” (a badge that, in the course of events, proved markedly less effective than a black, plain “VIP” badge with no “special” status), I found myself passing through turnstiles, caressing the pink silken curves of Tracey Emin’s neon sculpture at White Cube’s booth, laughing merrily, then squinting grimly as if involuntarily recalling the privations of Soviet times, with Emilia and Ilya Kabakov. Through the velvet ropes I swanned like a pro; but inside I was faking it. A nonentity, I had never been to Europe and had reached middle age without even thinking about it, like the 90 percent of my fellow Americans who don’t even have a passport.

I didn’t know what it might do to me, or what I would make of it—Europe that is. In grad school I’d read the requisite novels by Henry James, and in the years since a parade of mad tableaux have enacted themselves in my head: most often Cybill Shepherd in Peter Bogdanovich’s Daisy Miller, young and fresh and impetuous, the girl who dared convention and came down with pneumonia after a romantic assignation after dark in Rome’s Coliseum and, well, as Susan Sontag used to say, let’s not go there.

On second thought, maybe that had been my abiding fault—my fear of going there. People would ask why I’d hadn’t been abroad. Oh, I’m such a homeboy, I would laugh, or—it’s so expensive there, it’s not for the working man. Doesn’t a single gallon of gas cost thirty dollars? Doesn’t a ham sandwich cost, like, fifty? Invited to Basel, I nearly declined because my wife—who’d also been asked—couldn’t make it due to a pre-existing gig of longstanding in LA. But finally, I said to myself, oh, for Christ’s sake, Kevin, just say yes. You don’t want to turn into an old man who refused to go to Europe when he had the chance. You said yes to everything else all your life, why stop now.

And yet I so didn’t want to go alone! So I called my bud, London-based artist Tariq Alvi, and hollered at him long distance from my office. “Look, Tariq, I’ve been invited to read poetry in Basel and the students have arranged an apartment for me three minutes away from the Halle Messe and Dodie can’t come. Though it’s terribly short notice, can you come to Switzerland next week and be my roommate?” At first my appeal nonplussed him but I was so needy, a sad-voiced flageolet, that a day or so later he sent me an e-mail to say he was in. Yippie! Dodie was glad I’d have a pal, though perhaps a little jealous since she’s fond of him as I am, but at the end of the day it was settled that I would leave San Francisco on a Saturday, arriving in Basel on Sunday, and that our London friend would join me in my pensione sometime Monday.

At least that was my plan. You don’t want to hear how my plane couldn’t get off the runway at SFO, so that I missed my flight at JFK, nor about my lonely layover at Heathrow, a lag so dull that, driven to distraction, I sat down for a manicure for the first time in my life—merely to kill time.

At least that was my plan. You don’t want to hear how my plane couldn’t get off the runway at SFO, so that I missed my flight at JFK, nor about my lonely layover at Heathrow, a lag so dull that, driven to distraction, I sat down for a manicure for the first time in my life—merely to kill time.

I’m framing this essay in confidence, that you’ll enjoy hearing the impressions of a mere nobody brave enough to walk the halls of 300 galleries, 2,000 artists, 1,100 curators and museum personnel, 70,000 smart visitors, and whole slews of Swiss people they assured me would speak English but didn’t. The great thing was spotting, as soon as I got out of the cab, eternally glamorous Clarissa Dalrymple, the curator who had discovered Matthew Barney and hired an unknown Robert Mapplethorpe to photograph her little boy, in the nude of course. I think I started crying when I saw her, because the airline had lost my bags, and I had nothing but a camera, about sixty Swiss francs, and a dirty old suit. She took me in hand and slapped some sense in me. Since Venice, she said, she had already lost all her luggage, and her wallet, and both had found their way back to her. She fastened her wonderful eyes on me and her lips slipped into a wry smile. “So there’s hope for you yet, Kevin,” she said briskly. From then on I never gave up completely, not even when things got grim.

Few of the students of Frankfurt’s Staedelschule had ever been to a poetry reading before hiring me, but then again, few of them had ever embarked on an undertaking as big as the “Artists Lounge” they had agreed to build and staff at the request of Sam Keller, Art Basel’s departing director-in-chief. The Lounge transformed a relatively underused assembly room, big enough to host the Crown Inn ball in Jane Austen’s Emma and with large helpings of Regency detail, into an enchanted Alpine tiki garden with a psychedelic twist (think of Peter Hall’s setting for mid-1960s Midsummer’s Night Dream.) When I got to the hall, a fresh-faced Canadian lad jogged up two sets of marble steps and, with antelopean ease, hopped up onto the wooden platforms his confreres were garnishing with debris, branches and twigs pulled off of actual Alps. This was David Catherall, the young art student assigned as my handler. I asked him what kind of artwork he liked to make when not doing this backstage Father Christmas transformation scene. He had showed his work in San Francisco, of all places, at the newish Silverman Gallery, where he had coaxed ordinary molecules of LSD and of alcohol into Cronenbergian supergrowth, ghost honeycombs of pastel crystal. “Don’t know how that one cleared your American customs.” But in general, Catherall avoids association with any particular medium, for “it really varies and depends on the project, also you probably couldn’t nail it to a theme either… I also did a kind of time travel film about going back to the point in time when man and myth were created.”

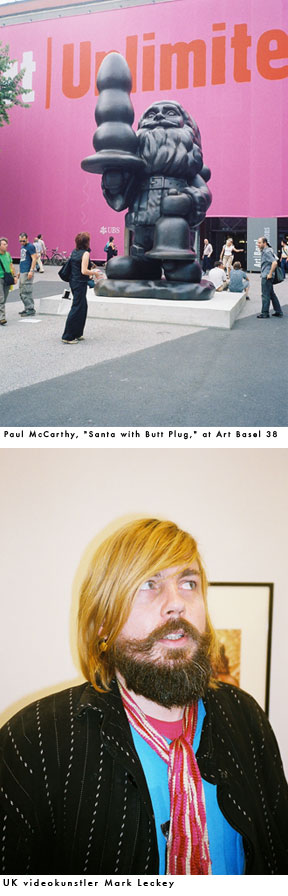

Before long, David C. had introduced me to a whole swarm of Staedelschulites, many of them students of the UK video and installation artist Mark Leckey. With various degrees of anxiety we all of us were waiting for Leckey, hoping for his nod of approval, a curt “well done.” In life, Leckey is immensely personable, pragmatic, and generous; his full cut sleeves and striped trousers, his hair tumbled atop his head in pincushion form, gave him the tousled look of the Beatles, perhaps right before their Rishikesh pilgrimage to consult the Maharishi.

Before long, David C. had introduced me to a whole swarm of Staedelschulites, many of them students of the UK video and installation artist Mark Leckey. With various degrees of anxiety we all of us were waiting for Leckey, hoping for his nod of approval, a curt “well done.” In life, Leckey is immensely personable, pragmatic, and generous; his full cut sleeves and striped trousers, his hair tumbled atop his head in pincushion form, gave him the tousled look of the Beatles, perhaps right before their Rishikesh pilgrimage to consult the Maharishi.

In the meantime there were a million things to see and do and not enough time for either.

I was most excited to read in the program that the one and only “Sturtevant” was to appear on stage, interviewed by Hans-Ulrich Obrist of London’s Serpentine Gallery, and the ethereal, scary Beatrix Ruf from the Kunsthalle Zurich. Ever since writer Bruce Hainley and director John Waters canonized Elaine Sturtevant in their enthusiastic art companion Art, a Sex Book I had been drawn to her legend with the weak helplessness of the fag. “Sturtevant” (she shows by her last name, rather like Greta Garbo would often by identified merely as “Garbo” in her mid-MGM period) had entered the art world in the 1960s with an audacious series of exhibitions in which she copied, stroke by stroke, all the best-known artists of her day, executing Warhols, Jasper Johnses, Frank Stellas, so that people didn’t know what to make of her. Her practice put into play all sorts of questions about originality, authenticity, the position of the “readymade,” the limits of the “postmodern.” And then she faded from sight for many years, then was back, and I cheered and screamed for minutes on end, in the corrugated cardboard “Art Lobby” room, as she made her simple, but effective entrance. “She looks quite smart,” Tariq whispered.

Indeed she did. Her short white hair curled around her face, and her long, shapely nails were painted the exact shade of orangey pink Warhol and Gerald Malanga seemed to favor most in those “Flowers” silkscreens. I loved her look, her big grin, her zest for life, everything about her. But then, after awhile, I tired of her. Poor thing, she was there to show a new video, “Spinoza in Las Vegas,” but it wouldn’t play. “Did you break it?” she hectored the apologetic tech. She had laid the piece in Las Vegas because, she announced, Vegas was a city completely devoid of any interiority. In my front row seat I must have made a moue because—sharp thing!—she pounced on my hesitation like a cat. “What? You disagree?” she snapped. “Well, sure, I mean, Vegas has, you know, like,” there I was, mumbling, massacring the Queens’ English, “Vegas has got just as much interiority as anywhere else.” It’s not like she lives in ancient Athens, she lives in Paris for God’s sake, why beat up on Las Vegas?

Indeed she did. Her short white hair curled around her face, and her long, shapely nails were painted the exact shade of orangey pink Warhol and Gerald Malanga seemed to favor most in those “Flowers” silkscreens. I loved her look, her big grin, her zest for life, everything about her. But then, after awhile, I tired of her. Poor thing, she was there to show a new video, “Spinoza in Las Vegas,” but it wouldn’t play. “Did you break it?” she hectored the apologetic tech. She had laid the piece in Las Vegas because, she announced, Vegas was a city completely devoid of any interiority. In my front row seat I must have made a moue because—sharp thing!—she pounced on my hesitation like a cat. “What? You disagree?” she snapped. “Well, sure, I mean, Vegas has, you know, like,” there I was, mumbling, massacring the Queens’ English, “Vegas has got just as much interiority as anywhere else.” It’s not like she lives in ancient Athens, she lives in Paris for God’s sake, why beat up on Las Vegas?

After recalling how she had to be dragooned into showing her work at the current WACK! exhibition of 1970s feminist art down at MOCA, Sturtevant rolled her eyes as those who would deem her a feminist anyhow. “They haven’t read my writing,” she roared. “Your important writing,” murmured Obrist at her elbow. “There are two things I don’t like about my writeups. They always start with my age. They don’t do that writing about male artists. And they always say, although she denies being a feminist, she is one anyway. They just don’t get it.” To recap, she dislikes feminism because originally, although they try nowadays to downplay it, feminists wanted to murder men, and she’s not into that. I tried to picture Sturtevant in middle age, alarmed by cadres of New York art world Girondists—at what dinner party, at what opening, was she apprised of their secret plans to massacre men? None of my misgivings about her severity prevented me from approaching her at lecture’s end and to proffer my autograph book, begging for a signature. She glanced up at me, her expressive eyes hard with disappointment and, like Bartleby, she muttered, “I prefer not to.”

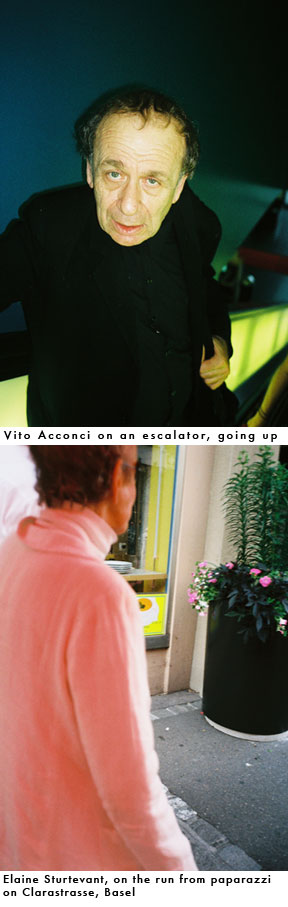

I swallowed, hard. “Well, then, would you mind if I took your picture?” Since cameras had been snapping and clicking during her entire press conference, I wasn’t anticipating any problem. “Don’t,” she said simply, a dismissal absolute.

Then she turned a corner and popped into the photo booth of Ezra Petronio, who was snapping Polaroids of fair bigwigs, where she posed gaily for dozens of candids, arm in arm with a tame curator guy. Ooh, that upset me something fierce it did. Afterwards, something in me rose up, like steel, in my heart and I vowed to stake her out as heartlessly as any paparazzo. In the days to come I saw her often, often with her London gallerist Anthony Reynolds, trotting down Clarastrasse for a bite to eat, surveying inferior pictures by others with wonder and disdain. Tariq was horribly embarrassed by my attempts to annoy her. “You’re no better than a stalker,” he reproved. Bruce—Bruce Hainley—forgive me for parting ways in this one crucial arena. She’s great, she’s a god and a genius, the Spinoza of our time and yet, she rubbed me the wrong way on some level of privilege or whatever? I remember thinking, she’s just like Katharine Hepburn, case closed.

Great art stars paraded about me, bent and kissed collectors left and right, and some of them I photographed, others I missed. Takashi Murakami walked past me when I didn’t have my camera ready. On another occasion, outside the big hall Tariq and I took refuge from a morning thunderstorm under a big umbrella at L’Escale, an open air cafe adjoining Art Unlimited, and we visited with a friend of Tariq’s from London who was sitting there with two people. “This is my friend who I do yoga with,” Tariq said. She was amiable, sober, quick to smile, and she seemed quite fond of Tariq so that it made me like her even more. Afterwards he remarked, “That was Tomma Abts,” and I was starstruck in retrospect, an odd feeling. “Why didn’t you tell me?” I pleaded. “She is the 2006 Turner Prize winner!” but I suppose my treatment of Sturtevant made him wary of telling me anything about anybody. He also spotted Wolfgang Tillmans hurling himself about in Art Unlimited, while in Art Basel proper, two giant floors of the top blue chip galleries in the world, he paused outside Timothy Taylor’s pristine space, indicating like crazy that I was to keep an eye on the blonde seated at the table. She was in her late thirties, a little brooch pinning down her breast, clear polished nails, otherwise all cashmere, cream and cocoa. Really just perfect. “She is the daughter of Princess Margaret,” whispered Tariq. “Just, look at her, who else could she possibly be?” Then he backed down. “She’s one of the royals,” he said. I didn’t try to get her picture, thinking that somewhere quite close the Secret Service of England was probably lurking, but many others acquiesced, after a recon of my nametag and the discovery that I was some sort of artist. But where was Lucian Freud? I never saw him, but you can’t be everywhere.

Great art stars paraded about me, bent and kissed collectors left and right, and some of them I photographed, others I missed. Takashi Murakami walked past me when I didn’t have my camera ready. On another occasion, outside the big hall Tariq and I took refuge from a morning thunderstorm under a big umbrella at L’Escale, an open air cafe adjoining Art Unlimited, and we visited with a friend of Tariq’s from London who was sitting there with two people. “This is my friend who I do yoga with,” Tariq said. She was amiable, sober, quick to smile, and she seemed quite fond of Tariq so that it made me like her even more. Afterwards he remarked, “That was Tomma Abts,” and I was starstruck in retrospect, an odd feeling. “Why didn’t you tell me?” I pleaded. “She is the 2006 Turner Prize winner!” but I suppose my treatment of Sturtevant made him wary of telling me anything about anybody. He also spotted Wolfgang Tillmans hurling himself about in Art Unlimited, while in Art Basel proper, two giant floors of the top blue chip galleries in the world, he paused outside Timothy Taylor’s pristine space, indicating like crazy that I was to keep an eye on the blonde seated at the table. She was in her late thirties, a little brooch pinning down her breast, clear polished nails, otherwise all cashmere, cream and cocoa. Really just perfect. “She is the daughter of Princess Margaret,” whispered Tariq. “Just, look at her, who else could she possibly be?” Then he backed down. “She’s one of the royals,” he said. I didn’t try to get her picture, thinking that somewhere quite close the Secret Service of England was probably lurking, but many others acquiesced, after a recon of my nametag and the discovery that I was some sort of artist. But where was Lucian Freud? I never saw him, but you can’t be everywhere.

I did get to meet Vito Acconci, who gave us a spirited account of the early days of performance art—of the moment when poets turned directly to the body after the Fluxusesque waves knocked the mid-60s New American poetry slightly off its course and into a place where language met up with its own materiality. It was wonderful having Acconci read aloud from this poetry—I never thought I’d actually hear him go back and re-do this work. Once, ten years ago, John Ashbery gave a program of poems from his very earliest poems, and after hearing him read “He,” I told my friends I had had a religious conversion. At the last Orono conference in Maine on “Poets of the 1940s” we heard Jackson Mac Low read from his very first poem and my hair started curling up like Christopher Lloyd in Back to the Future. I tried mumbling some of my excitement to Vito Acconci and he was very kind, posing for endless photographs, signing anything the students put in front of him and in general, he was the anti-Sturtevant.

I kept brooding over Elaine Sturtevant, and Tariq played the gentle voice of reason. “Are you sure you aren’t mixing her up with Elaine Stritch?” he asked. “They’re a lot alike, and you have that love-hate relationship with Elaine Stritch.”

“I do not have a love-hate relationship with Elaine Stritch!”

In fact I did, but doesn’t everyone? For the benefit of the non-gay among you, I’ll explain that Elaine Stritch is a revered stage actress and musical performer of great age whose whole shtick is that she was a lush and can remember only the pretty edges of things, but she’s still here. She originated “The Ladies who Lunch” in Stephen Sondheim’s Company, and “Why Do the Wrong People Travel,” in Noel Coward’s 1959 Sail Away, and yes, everyone who knows anything about Stritch has a love-hate relationship with her. So maybe I was “crossing over,” as they say in Berkeley therapy circles, and maybe Tariq was right.

Fair organizers told us for days that a “surprise guest” was coming—I guess it’s a tradition there, that someone would be a surprise, which I love. But David Catherall somehow knew, his ear to the ground, that it was going to be Malcolm McLaren this year. McLaren was great, so personable and smart. He sat down on a chair and launched into the story he must have told a million times before, how he gave birth to punk, and yet managed to make it seem like he was remembering it for the first time. Nowadays with superhero movies and “reboots,” producers are all looking for what they call “origin stories,” like the last Batman movie, and I’ve never really understood why the need for the origin story, but when McLaren described the little rubber fetish crowd he trawled among, and selling things off the walls of somebody else’s shop, then having to replace them, I felt a chill, as though all in the hall were present not only at the birth of Punk, but at the birth of capitalism too. After the talk was over, he seemed to scurry away like a pile of autumn leaves, blown by a November squall, but when the students raced after him, he slowed visibly and signed everything we thrust in front of his face, and posed for dozens of pictures. Maybe he’s horrible or whatever, but he’s the man.

Fair organizers told us for days that a “surprise guest” was coming—I guess it’s a tradition there, that someone would be a surprise, which I love. But David Catherall somehow knew, his ear to the ground, that it was going to be Malcolm McLaren this year. McLaren was great, so personable and smart. He sat down on a chair and launched into the story he must have told a million times before, how he gave birth to punk, and yet managed to make it seem like he was remembering it for the first time. Nowadays with superhero movies and “reboots,” producers are all looking for what they call “origin stories,” like the last Batman movie, and I’ve never really understood why the need for the origin story, but when McLaren described the little rubber fetish crowd he trawled among, and selling things off the walls of somebody else’s shop, then having to replace them, I felt a chill, as though all in the hall were present not only at the birth of Punk, but at the birth of capitalism too. After the talk was over, he seemed to scurry away like a pile of autumn leaves, blown by a November squall, but when the students raced after him, he slowed visibly and signed everything we thrust in front of his face, and posed for dozens of pictures. Maybe he’s horrible or whatever, but he’s the man.

From morning to late, late night the trees of the Artists’ Lounge trembled with the stomping of feet. A Berlin cake patisserie had been imported to give the place some elegance and a taste of champagne, and under a Western tent raged the Golden Rausch bar, manned by students, staff members, and dignitaries of the Staedelschule in uniform black T-shirts and hats. There was something of a cabaret feel last week, but a Dada cabaret, in which the next act might be a professor lecturing on wind tunnels. They had me reading, from my own work and others, every day at 12:30, in big, expansive, ninety-minute sets—the sort of time poets are only rarely allowed. Most of the time they want us to just give little haiku miniatures of 8 to 10 minutes. It was fitting that we were on display in the so-called “Art Unlimited” hall in which oversized, indeed super-majestic art was given room, so you had things like the great construction of Michael Stevenson’s “Persepolis,” or the young UK artist William Hunt submerged yet singing through an oxygen mask inside a BMW filled with murky, golden water. I wound up reading not only poetry, but parts of my novels, sketches of urban life, more than a few of my Selected Amazon Reviews, edited by Brent Cunningham (Hooke Press, 2006), and we put on plays. Lots of little plays! Happily there were a fair number of artists milling around, some I’d worked with before, some not, but I tried to dragoon many of them up on the stage with me. I’d direct as we worked, and yet wangle all the plum parts. Chris Johanson and Jo Jackson were in Basel, with their little dog, Raisin—I put all three of them on the stage. Chris and Jo are superb, imaginative actors as well as terrific artists, and best of all, they’re good sports.

US poet Susana Gardner, who now lives in Basel, showed up, with a Basel-born writer friend called Kathrin Shaeppi. They took me and Tariq on an insider’s walking tour through the city. We went everywhere, floating across the Rhine on a low boat, across the Mittlere Brucke on foot, up these cobblestone paths to the Cathedral where Erasmus of Rotterdam lies buried. Kathrin pointed out The Three Kings, said to be the most expensive hotel in Switzerland. (Days later Tariq and I pretended we were staying there, walking through its various restaurants and cafes as though we just couldn’t decide which one to patronize.) We stopped for tea at a converted orphanage or prison or something that now looks very elegant, and I lost my favorite gray cardigan somewhere along the way, but oh, what a pleasant day and what a treat. I don’t think I thought about art for hours—at least not about the “market.”

US poet Susana Gardner, who now lives in Basel, showed up, with a Basel-born writer friend called Kathrin Shaeppi. They took me and Tariq on an insider’s walking tour through the city. We went everywhere, floating across the Rhine on a low boat, across the Mittlere Brucke on foot, up these cobblestone paths to the Cathedral where Erasmus of Rotterdam lies buried. Kathrin pointed out The Three Kings, said to be the most expensive hotel in Switzerland. (Days later Tariq and I pretended we were staying there, walking through its various restaurants and cafes as though we just couldn’t decide which one to patronize.) We stopped for tea at a converted orphanage or prison or something that now looks very elegant, and I lost my favorite gray cardigan somewhere along the way, but oh, what a pleasant day and what a treat. I don’t think I thought about art for hours—at least not about the “market.”

At Art Basel everything was on a grander scale than I’m used to, well, I have been to Niagara Falls a few times. That was big but this was bigger. In our apartment on Minna Street, South of Market in San Francisco, we can hang only very small works—preferably blotter acid size though we can run up to note card dimensions. One of our favorite young artists, Matt Greene, who shows at Peres Projects in LA and Berlin, had to cut the top third and the bottom third away from his painting to make it fit our space—Procrustean solution—but so clever is Matt that it still looks great. At Art Basel Procrustes has been deposed entirely, and the reigning deity is—is whom? Whomever is his opposite number—Bruce Banner I suppose. Everything was conceived in operatic terms, as though artists feared subtlety itself, or that subtlety might bore their audience.

One’s eye was drawn to those walls of late de Koonings—everywhere—how many paintings did he make in the last six months of his life one wonders—an equal number of big Bacons—I thought they were supposed to be so scarce? Vast Damien Hirst paintings, in sets even. More Tracey Emin. Deitch was showing Barry McGee’s famous graffiti-ed wreck of a men’s room, in one corner of which, through the miracle of audioanimatronics, a stolid tagger extends his spray can from left to right down a strip of bleary mirror, again and again. It looks so real, I thought, well, that’s different.

One’s eye was drawn to those walls of late de Koonings—everywhere—how many paintings did he make in the last six months of his life one wonders—an equal number of big Bacons—I thought they were supposed to be so scarce? Vast Damien Hirst paintings, in sets even. More Tracey Emin. Deitch was showing Barry McGee’s famous graffiti-ed wreck of a men’s room, in one corner of which, through the miracle of audioanimatronics, a stolid tagger extends his spray can from left to right down a strip of bleary mirror, again and again. It looks so real, I thought, well, that’s different.

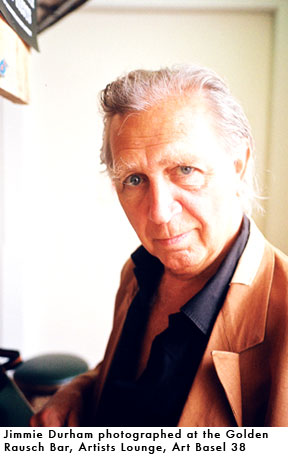

I went to a panel of Production and Overproduction, etc, in which three artists were quizzed about the current boom market and if it was possible that some art might be created solely to satisfy it. In their different ways, Martin Creed, Christian Boltanski and Jimmie Durham all swore that they personally each “meant” all of their artworks, though others, they warned darkly, had crossed over to the dark side.

Durham recalled going to his first art fair, some ten years ago, in Paris, and wondering at the gullible French dealers offering so many “fake Jean Michel Basquiats.” Then came the click. The dealers had bought in good faith, and indeed Basquiat had made each one, but he had made his own “fake Basquiats” (to take advantage of the market) before his own death. During the Q&A, a young artist expressed bewilderment with the current climate, in which no emerging artist could attain notice unless she was using wildly expensive materials or enjoyed extensive financial backing from her gallery. “I beg to differ,” said Boltanski. “Invited to the Moscow Biennial, I filled the entire Opera House with old coats.” He paused, as if to reflect. His huge, expressive eyes gleamed like the crystals of acid David Catherall had mounted in a corner of San Francisco’s Silverman Gallery. I’m here to tell you, Boltanski looks a lot like Hitchcock, sort of sinister and jolly. He paused, then spoke again. “Total cost of those coats, five dollars. No, you do not need expensive materials if you have the dream.” I kept thinking, that must have been back in the day when five dollars bought a lot of old coats.

I ran smack into Tadao Ando, the Japanese architect who didn’t seem to speak a lot of English, just like the majority of Swiss people I came across. Ando became famous without a degree in architecture or even any training, just started designing buildings from his day job as a postman or sewer worker or couturier, I forget what it was, and in any case three or four people named five different occupations. He had a gleam in his eye as though to say, you can do it too.

I ran smack into Tadao Ando, the Japanese architect who didn’t seem to speak a lot of English, just like the majority of Swiss people I came across. Ando became famous without a degree in architecture or even any training, just started designing buildings from his day job as a postman or sewer worker or couturier, I forget what it was, and in any case three or four people named five different occupations. He had a gleam in his eye as though to say, you can do it too.

Cutest artists I met at the fair? I can’t decide, Terence Koh or Cyprien Gaillard. Koh was resplendent in a black jacket heavy with hundreds of appliquéd studs, like Linda Evans in the last, Jacobean season of Aaron Spelling’s dynasty. I met him at a party about 2 in the morning in a heavily derelict part of town, a deserted, torn up patch of country that looked as though US bombers had flown over it dropping napalm and salt forty years ago, but wait, I thought, Basel is probably one city where US bombers still haven’t attacked. Terence Koh, the “Asian Punk Boy” as he was formerly known, was all business even in the early hours of the morning. “Why do I look so familiar?” he said. “You probably remember me from my spread in Butt magazine.”

Cyprien Galliard I met during completely different circumstances, during the day for one, indoors for another. His artworks were everywhere during the fair, I kept seeing him in booth after booth. Across town, in the so-called “young people’s art fair,” Liste 07, they had one of his photos and a video installation, right next to the bar so you know his exposure was vast. Like Robert Smithson, like a French Robert Smithson, like a French Al Gore, his work is all about the devastation we’ve done to the earth and at first, I resisted it, then its sinuous, fairy tale beauty came to haunt me. When I spoke with him I was, like, all question marks, he sounded like the boy next door–he sounded American I mean. Turns out he was raised in North Beach, the old time bohemian section of San Francisco where City Lights is, where Coit Tower rises to a phallic, fireplug peak.

And three golden apples, one each for my boy saints of the Staedelschule, David Catherall, Kristoffer Frick, and Ryan Siegan-Smith. Whenever I felt whipped by Sturtevant’s slights, I had only to gaze at one of these fellows and I got my bone back. They are like the angels who wander through Rilke, whispering, “You must change your life,” and all nature hollers back, “Okey-doke, it’s a deal.”

And three golden apples, one each for my boy saints of the Staedelschule, David Catherall, Kristoffer Frick, and Ryan Siegan-Smith. Whenever I felt whipped by Sturtevant’s slights, I had only to gaze at one of these fellows and I got my bone back. They are like the angels who wander through Rilke, whispering, “You must change your life,” and all nature hollers back, “Okey-doke, it’s a deal.”

One night I spent packing and repacking a suitcase filled with Swiss souvenirs for my loved ones back home, and accidentally, I must have dashed into the basin a half-filled glass of water I found on a shelf in the bathroom medicine cabinet. I never thought that Swiss tumbler might contain something in it—a pair of contact lenses to be exact—contact lenses fresh from the eyes of the 29 year old visual artist Benjamin Saurer! Late that night he popped into my bedroom all apologetic, wearing only a sketchy pair of midnight blue undershorts that gave his long ribcage the majesty of a beach god, the young Neptune perhaps. “I’m sorry,” he said, “sorry to wake you but have you seen my lenses?” More particularly he thought I might have swallowed them. Would they lacerate my insides? He mimed stomach ache, then vomiting. I was so mortified and he was so sweet!

Well, I wasn’t feeling pain. Just embarrassment. At the Artists Lounge, in a slouch hat, young Saurer would ease onto a piano bench at the drop of a hat and perform rousing, extended riffs on Barry Manilow, Willie Nelson, Lionel Richie, Johnny Cash. With his younger sister, Anna, and his contemporary Heike Staudacher, Saurer fronts a Carter Family style bluegrass/autoharp/zither trio called “Angels’ Voice” and at the Staedelschule culls images from accounts of 16th century exploration, refracting European fears of the “barbaric cannibals” profiteers decimated in indigenous and Caribbean Americas, on riotously polite patterns of wrapping paper. If you read this in English, Ben, I’m sorry I splashed your lenses down that sink. I would send a gang of plumbers to 83 Kleinertalstrasse, they could wrench apart the pipes, but by now I hope you can see again and you haven’t lost any finesse. After all, I’m leaving the future in your hands.

All photos by Kevin Killian, cover photo is of Emilia and Ilya Kabakov at Art Basel 38