Curtains for Richard Widmark

28.03.08

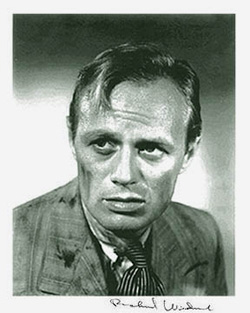

It had to happen sometime, but the news of Richard Widmark’s death on March 24 in Connecticut threw me for a loop, for I guess I thought he would always be there, just under the surface, one of the last troubling memories of my childhood, and not to mention a great star largely in eclipse for the past 40 years. His film debut, the part that made him a star, came before I was born, when he played the gangster Tommy Udo in Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947). Tommy was demented, manic, with big saucer eyes and beautiful soft blond hair—a little bit like Tommy by the Who (but more like Cousin Kevin from the same “rock opera”)—and Widmark made movie history by tying up an old lady in a wheelchair and pushing her down a flight of shadowy stairs just for kicks, while his voice soared in a high pitched giggle like a girl’s. I suppose moviegoers had never seen anything like this and Widmark was nominated for an Oscar. “Tommy Udo” became a blessing and a curse for our hero, for it was such a strong performance that it overshadowed his later, more subtle work, the same way that playing Norman Bates was at once the apex and ruin of Tony Perkins’ career—although Perkins actually never gave us any later, more subtle work. But anyhow, the name of Tommy Udo was known around the world. In Cologne the parents of baby Kier looked down at their newborn, giggling maniacally, and in a moment of German precognition they said, “Let’s call him Udo,” and another star was born.

It had to happen sometime, but the news of Richard Widmark’s death on March 24 in Connecticut threw me for a loop, for I guess I thought he would always be there, just under the surface, one of the last troubling memories of my childhood, and not to mention a great star largely in eclipse for the past 40 years. His film debut, the part that made him a star, came before I was born, when he played the gangster Tommy Udo in Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947). Tommy was demented, manic, with big saucer eyes and beautiful soft blond hair—a little bit like Tommy by the Who (but more like Cousin Kevin from the same “rock opera”)—and Widmark made movie history by tying up an old lady in a wheelchair and pushing her down a flight of shadowy stairs just for kicks, while his voice soared in a high pitched giggle like a girl’s. I suppose moviegoers had never seen anything like this and Widmark was nominated for an Oscar. “Tommy Udo” became a blessing and a curse for our hero, for it was such a strong performance that it overshadowed his later, more subtle work, the same way that playing Norman Bates was at once the apex and ruin of Tony Perkins’ career—although Perkins actually never gave us any later, more subtle work. But anyhow, the name of Tommy Udo was known around the world. In Cologne the parents of baby Kier looked down at their newborn, giggling maniacally, and in a moment of German precognition they said, “Let’s call him Udo,” and another star was born.

Hathaway made Kiss of Death for Twentieth Century Fox, and the picture has the trademark Fox noir look that’s been described to death, for indeed the noir pictures, so undervalued in their time, have come to dominate all other genres in today’s thought, so that if it isn’t noir, it ain’t worth seeing. Widmark plunged in under studio contract and made film after film, many of them in nervous, fidgety parts that called for lots of sweat on his huge, billboard-size forehead, and variations on the notorious blond giggle. But he started playing heroes, too, though usually with something “off” about them. He couldn’t shake the Tommy Udo image, for it had become a huge hit with kids—and worse, with comedians who did impersonations. Frank Gorshin kept Tommy Udo alive for 20 or 30 years, singlehandedly, with his his nightclub act. In fact Gorshin looked a lot like Widmark and eventually played sub-Widmark psychopaths in film (in Dragstrip Girl and That Darn Cat!) and on TV—most memorably as the Riddler on the Batman TV show (ten times, thus preserving the Tommy Udo of Widmark into a new, “pop” generation). But seeing Gorshin again and again must have given Richard Widmark the slow burn, unable to escape the spectacle of his own juvenile image.

Hathaway made Kiss of Death for Twentieth Century Fox, and the picture has the trademark Fox noir look that’s been described to death, for indeed the noir pictures, so undervalued in their time, have come to dominate all other genres in today’s thought, so that if it isn’t noir, it ain’t worth seeing. Widmark plunged in under studio contract and made film after film, many of them in nervous, fidgety parts that called for lots of sweat on his huge, billboard-size forehead, and variations on the notorious blond giggle. But he started playing heroes, too, though usually with something “off” about them. He couldn’t shake the Tommy Udo image, for it had become a huge hit with kids—and worse, with comedians who did impersonations. Frank Gorshin kept Tommy Udo alive for 20 or 30 years, singlehandedly, with his his nightclub act. In fact Gorshin looked a lot like Widmark and eventually played sub-Widmark psychopaths in film (in Dragstrip Girl and That Darn Cat!) and on TV—most memorably as the Riddler on the Batman TV show (ten times, thus preserving the Tommy Udo of Widmark into a new, “pop” generation). But seeing Gorshin again and again must have given Richard Widmark the slow burn, unable to escape the spectacle of his own juvenile image.

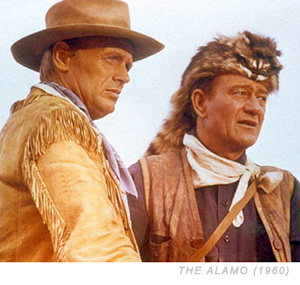

Though he had begun playing heroic roles as early as 1949, Widmark felt stereotyped at Fox and was eventually humiliated when Zanuck declined to pick up his contract when it ran its course. A period of “independent” stardom followed, and perhaps this was the smart option, for now he could pick and choose his own roles, and for the most part he chose, if not wisely, at any rate colorfully, and 50s people seemed to want to see him in any old thing. He played in dramas, comedies, thrillers, Westerns, science fiction, even horror. By the late 1950s he was regularly cited as one of the top male stars, even as his choices became more and more outlandish (and to my eyes, more interesting). He played the Dauphin in Otto Preminger’s notorious film, Saint Joan, with Jean Seberg, written by Graham Greene no less. There might have been a way in which he wasn’t a romantic lead—what sex appeal he had was limited—so his leading-man-ness got diverted into playing the same sorts of parts that Robert De Niro plays today.

Though he had begun playing heroic roles as early as 1949, Widmark felt stereotyped at Fox and was eventually humiliated when Zanuck declined to pick up his contract when it ran its course. A period of “independent” stardom followed, and perhaps this was the smart option, for now he could pick and choose his own roles, and for the most part he chose, if not wisely, at any rate colorfully, and 50s people seemed to want to see him in any old thing. He played in dramas, comedies, thrillers, Westerns, science fiction, even horror. By the late 1950s he was regularly cited as one of the top male stars, even as his choices became more and more outlandish (and to my eyes, more interesting). He played the Dauphin in Otto Preminger’s notorious film, Saint Joan, with Jean Seberg, written by Graham Greene no less. There might have been a way in which he wasn’t a romantic lead—what sex appeal he had was limited—so his leading-man-ness got diverted into playing the same sorts of parts that Robert De Niro plays today.

In college I had a gay friend who loved Richard Widmark. Alfonso’s family had escaped Castro and the communist revolution in the late 1950s and he was a brute of a guy, very Javier Bardem in Before Night Falls. He was really into big blond fiftyish guys—what today you might think of as the Gary Busey type—and he had nicknamed Richard Widmark “Skidmark,” and could rhapsodize about his magnetism for literally hours at a stretch. Alfonso had a big apartment on New York’s Upper West Side, the sort of apartment that book editors live in in movies about Manhattan, but which in real life is reserved for the super rich. One day he wangled some sort of interview with his idol—a scam, but he claimed to Widmark’s rep that he worked for After Dark, the leading crypto-gay “entertainment” monthly of the day, and somehow went up to the Plaza and met “Skidmark” in a lavish suite. He came back all smiles and memories. “He is a lovely gent, Kevin, truly one of the last gentlemen of Hollywood, and I would suck his cock from here to Heaven if only God were merciful to his servants.”

In college I had a gay friend who loved Richard Widmark. Alfonso’s family had escaped Castro and the communist revolution in the late 1950s and he was a brute of a guy, very Javier Bardem in Before Night Falls. He was really into big blond fiftyish guys—what today you might think of as the Gary Busey type—and he had nicknamed Richard Widmark “Skidmark,” and could rhapsodize about his magnetism for literally hours at a stretch. Alfonso had a big apartment on New York’s Upper West Side, the sort of apartment that book editors live in in movies about Manhattan, but which in real life is reserved for the super rich. One day he wangled some sort of interview with his idol—a scam, but he claimed to Widmark’s rep that he worked for After Dark, the leading crypto-gay “entertainment” monthly of the day, and somehow went up to the Plaza and met “Skidmark” in a lavish suite. He came back all smiles and memories. “He is a lovely gent, Kevin, truly one of the last gentlemen of Hollywood, and I would suck his cock from here to Heaven if only God were merciful to his servants.”

In those days we didn’t have DVDs or videotapes and Widmark films were hard to see, except at revival theaters, but if you kept your ear to the ground, as Alfonso did, you could usually find one of his old shows playing somewhere midtown. We went to see Night and the City, in which Widmark plays Harry Fabian, an extroverted hustler/con artist bizarrely transplanted for some reason I forget to London’s underworld where he becomes involved in a shady scheme to promote wrestlers. Jules Dassin photographs Widmark from all angles, with what looks like flashlights directed at the underside of his jaw and chin, so you can see his Adams’ apple gulping when he lies, which is during every other sentence. The “noir” shadows and oblique angles get sometimes comical, but Widmark is memorable, really seeming to lose himself in the role, not showily as his contemporaries Kirk Douglas or Burt Lancaster might have played it, but scarily real. Alfonso said that this was the performance Dustin Hoffman aped for his Ratso Rizzo in Midnight Cowboy. “How do you know?” “Ay Kevin,” he laughed, “I ‘interviewed’ him for After Dark as well.”

In those days we didn’t have DVDs or videotapes and Widmark films were hard to see, except at revival theaters, but if you kept your ear to the ground, as Alfonso did, you could usually find one of his old shows playing somewhere midtown. We went to see Night and the City, in which Widmark plays Harry Fabian, an extroverted hustler/con artist bizarrely transplanted for some reason I forget to London’s underworld where he becomes involved in a shady scheme to promote wrestlers. Jules Dassin photographs Widmark from all angles, with what looks like flashlights directed at the underside of his jaw and chin, so you can see his Adams’ apple gulping when he lies, which is during every other sentence. The “noir” shadows and oblique angles get sometimes comical, but Widmark is memorable, really seeming to lose himself in the role, not showily as his contemporaries Kirk Douglas or Burt Lancaster might have played it, but scarily real. Alfonso said that this was the performance Dustin Hoffman aped for his Ratso Rizzo in Midnight Cowboy. “How do you know?” “Ay Kevin,” he laughed, “I ‘interviewed’ him for After Dark as well.”

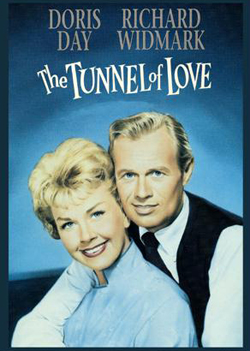

Or you could just stay at home and turn on the TV, where Richard Widmark and Doris Day seemed always to be playing in The Tunnel of Love, a rare Doris misfire from the 1950s. An affable, grumpy suburbanite who can’t get Doris pregnant, Widmark comes to believe the baby he’s adopted is his actual biological child. When I was a kid I was like, what? Both stars seem equally puzzled by the script and by the belabored, unfunny direction of Gene Kelly, a good dancer and an OK actor, but Hollywood’s worst filmmaker. The Tunnel of Love titillated me and Alfonso with its glimpses of Widmark as Connecticut schlub—for everyone knew he actually lived in Connecticut. We came to believe that the house in the movie was where he hung his hat “off camera” and made some futile plans, again like Ratso Rizzo, to get on a bus or train and leave dingy old Manhattan for the glamorous Widmarkian suburbs of Westport. But alas, it was not to be. Alfonso was such a fabulous creature of gay Manhattan I think he might have evaporated if he tried crossing the East River, and yet, oh how he loved his “Skidmark.”

Or you could just stay at home and turn on the TV, where Richard Widmark and Doris Day seemed always to be playing in The Tunnel of Love, a rare Doris misfire from the 1950s. An affable, grumpy suburbanite who can’t get Doris pregnant, Widmark comes to believe the baby he’s adopted is his actual biological child. When I was a kid I was like, what? Both stars seem equally puzzled by the script and by the belabored, unfunny direction of Gene Kelly, a good dancer and an OK actor, but Hollywood’s worst filmmaker. The Tunnel of Love titillated me and Alfonso with its glimpses of Widmark as Connecticut schlub—for everyone knew he actually lived in Connecticut. We came to believe that the house in the movie was where he hung his hat “off camera” and made some futile plans, again like Ratso Rizzo, to get on a bus or train and leave dingy old Manhattan for the glamorous Widmarkian suburbs of Westport. But alas, it was not to be. Alfonso was such a fabulous creature of gay Manhattan I think he might have evaporated if he tried crossing the East River, and yet, oh how he loved his “Skidmark.”

Un memento mori, Dodie and I are watching The Cobweb, Minnelli’s insane 1955 melodrama involving doctors and patients at an exclusive suburban sanitarium, and the struggle to pick up the right curtains for their lounge. Yes you heard me! On some level The Cobweb is an allegory for America I’m sure, and how we govern ourselves and our intricate system of checks and balances, but under Minnelli’s direction it’s more like, who can eat the most screen furniture. Widmark is the noble, liberal psychiatrist of the hospital—noble to a degree, but oddly blind to the quirks of his colleagues and blind also to the fact that his wife is pouting around the clinic and is played by Gloria Grahame, the perpetually unsatisfied vixen nightmare of US cinema. Lauren Bacall’s also on hand, as a young widow who’s lost both husband and child—so she’s vulnerable. Lillian Gish plays a Nurse Ratched prototype, mean as sin, while Olive Carey is her right hand man. For patients you have Susan Strasberg, Minnelli crush John Kerr, and Oscar Levant, the wisecracking clown of late night TV; while ruling the roost, clinic head, Charles Boyer, falling apart himself in a spectacular Fitzgerald-like collapse and intent on bringing everyone down with him. Each of them has the idea for the perfect pair of curtains for the patients’ lounge—but individually each lacks the power to impose an individual vision, so it’s politics as usual. Lillian Gish wants cheap curtains, without frills—the Republican way. Neglected Gloria Grahame lobbies for the curtains of an unsatisfied wife whose husband is falling for Lauren Bacall. And the patients want to make their own, the hell with baskets, let’s make curtains that express both our madness and our struggle for normalcy and sexual love!

Un memento mori, Dodie and I are watching The Cobweb, Minnelli’s insane 1955 melodrama involving doctors and patients at an exclusive suburban sanitarium, and the struggle to pick up the right curtains for their lounge. Yes you heard me! On some level The Cobweb is an allegory for America I’m sure, and how we govern ourselves and our intricate system of checks and balances, but under Minnelli’s direction it’s more like, who can eat the most screen furniture. Widmark is the noble, liberal psychiatrist of the hospital—noble to a degree, but oddly blind to the quirks of his colleagues and blind also to the fact that his wife is pouting around the clinic and is played by Gloria Grahame, the perpetually unsatisfied vixen nightmare of US cinema. Lauren Bacall’s also on hand, as a young widow who’s lost both husband and child—so she’s vulnerable. Lillian Gish plays a Nurse Ratched prototype, mean as sin, while Olive Carey is her right hand man. For patients you have Susan Strasberg, Minnelli crush John Kerr, and Oscar Levant, the wisecracking clown of late night TV; while ruling the roost, clinic head, Charles Boyer, falling apart himself in a spectacular Fitzgerald-like collapse and intent on bringing everyone down with him. Each of them has the idea for the perfect pair of curtains for the patients’ lounge—but individually each lacks the power to impose an individual vision, so it’s politics as usual. Lillian Gish wants cheap curtains, without frills—the Republican way. Neglected Gloria Grahame lobbies for the curtains of an unsatisfied wife whose husband is falling for Lauren Bacall. And the patients want to make their own, the hell with baskets, let’s make curtains that express both our madness and our struggle for normalcy and sexual love!

And yet Widmark transcends it all—he’s convincingly caring, empathetic, thoughtful. He almost looks as though he’s cracked a book. It’s easy to imagine him as the young Turk in the highly divisive world of private asylums, opposite the fading yet still fiery Boyer. Strange then, that his stardom should be such a thing of the past. Has any star, bar Arthur Kennedy, been so unjustly forgotten? And why? Maybe Widmark’s function—as the crazy psychopath visible under the mask of “good actor”—was completely subsumed by De Niro’s turn as Travis Bickle and we don’t need him in the cadre of cinema any longer. Could be. Over on Fox News that headstrong, opinionated pundit Roger Friedman (of FOX 411) has been lobbying for years about awarding an honorary Oscar to Widmark, or conversely Doris Day, and for years he’s gotten zilch for his campaigns. (I suppose he never saw The Tunnel of Love, otherwise he would have stopped campaigning for either actor long ago.) I can’t stand Roger Friedman, and yet I did agree with him on this one issue. The Academy should have given Richard Widmark every award there was to offer, for temerity alone. No one else could have played the prosecutor in Judgment at Nuremberg with the same steely-eyed, contemptuous grin. In a crazy cast that includes Judy Garland, Spencer Tracy, Montgomery Clift, Burt Lancaster, and Marlene Dietrich, Widmark manages to make himself top gun, rolling steel balls in his hand, spitting out anti-Nazi fire with every speech. Occasionally director Stanley Kramer just steps back and lets Widmark shatter the screen with meanness—and yet, he’s prosecuting Nazis, he’s entitled to that divine hard-assness, isn’t he? Montgomery Clift can hardly keep from passing out in the witness stand, while Judy Garland gives those nervous little laughs and pats what would be a neck in any other human being, and Widmark just glares.

And yet Widmark transcends it all—he’s convincingly caring, empathetic, thoughtful. He almost looks as though he’s cracked a book. It’s easy to imagine him as the young Turk in the highly divisive world of private asylums, opposite the fading yet still fiery Boyer. Strange then, that his stardom should be such a thing of the past. Has any star, bar Arthur Kennedy, been so unjustly forgotten? And why? Maybe Widmark’s function—as the crazy psychopath visible under the mask of “good actor”—was completely subsumed by De Niro’s turn as Travis Bickle and we don’t need him in the cadre of cinema any longer. Could be. Over on Fox News that headstrong, opinionated pundit Roger Friedman (of FOX 411) has been lobbying for years about awarding an honorary Oscar to Widmark, or conversely Doris Day, and for years he’s gotten zilch for his campaigns. (I suppose he never saw The Tunnel of Love, otherwise he would have stopped campaigning for either actor long ago.) I can’t stand Roger Friedman, and yet I did agree with him on this one issue. The Academy should have given Richard Widmark every award there was to offer, for temerity alone. No one else could have played the prosecutor in Judgment at Nuremberg with the same steely-eyed, contemptuous grin. In a crazy cast that includes Judy Garland, Spencer Tracy, Montgomery Clift, Burt Lancaster, and Marlene Dietrich, Widmark manages to make himself top gun, rolling steel balls in his hand, spitting out anti-Nazi fire with every speech. Occasionally director Stanley Kramer just steps back and lets Widmark shatter the screen with meanness—and yet, he’s prosecuting Nazis, he’s entitled to that divine hard-assness, isn’t he? Montgomery Clift can hardly keep from passing out in the witness stand, while Judy Garland gives those nervous little laughs and pats what would be a neck in any other human being, and Widmark just glares.

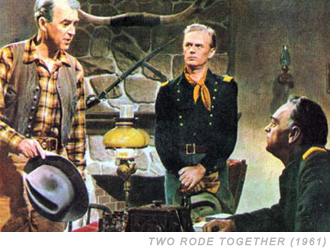

Or look at Two Rode Together (1961), Widmark’s first film for John Ford. James Stewart’s great of course, but as his evil “twin,” Widmark delivers a totally modern performance. They’re shackled side by side through most of the film, not literally but dramatically, and yet half the screen belongs to what you might think of as the “classic” US cinema, and the other half takes you into a later age, the “New American cinema” of the 1960s and 1970s. You could never count him out, not entirely. Except now it seems, at age 93, you can and you will, as the curtains come down on a fantastic world of frenzy and terror and compulsion.

Or look at Two Rode Together (1961), Widmark’s first film for John Ford. James Stewart’s great of course, but as his evil “twin,” Widmark delivers a totally modern performance. They’re shackled side by side through most of the film, not literally but dramatically, and yet half the screen belongs to what you might think of as the “classic” US cinema, and the other half takes you into a later age, the “New American cinema” of the 1960s and 1970s. You could never count him out, not entirely. Except now it seems, at age 93, you can and you will, as the curtains come down on a fantastic world of frenzy and terror and compulsion.