Creatures Who Stab Your Eyeballs and Eat Off Your Face and Slice Up Your Guts to Put on Pizza

02.10.14

John Henry Fleming’s a writer who lives in Florida, who teaches at a college in Florida, who writes novels and stories about characters whose lives are set, mostly, in Florida. You might think that the flattest US state would have so little to offer, but I say no Floridian garbage heap (what, in my turbid imagination amounts to a Floridian mountain) can surpass the prose fiction wanderings that John Henry Fleming has so devoutly zenned himself into for the last going on what, nearly thirty years?

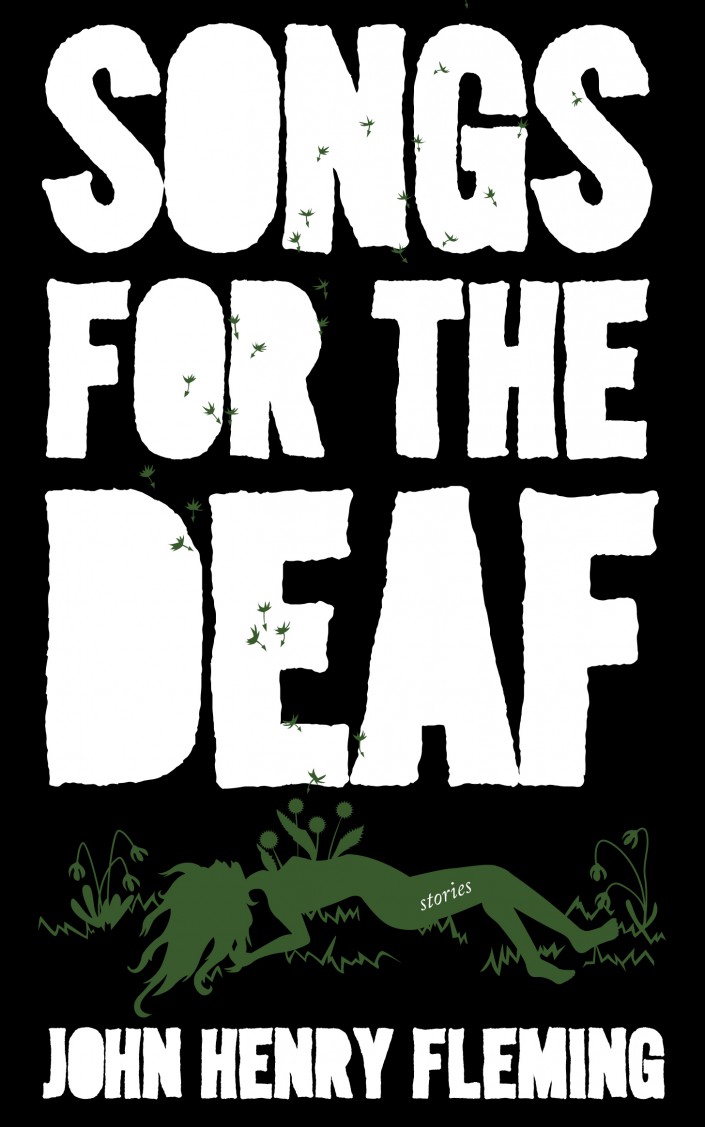

Yeah, this dude should thou read. His stories are full of the unexpected, the strange, the fun and funny narrative musings of suburbia tossed into a snowglobe spun round and lit afire—melted fake snow. His most recent book is Songs for the Deaf, published by Burrow Press. This story collection will make your dad’s balls drop again. Fleming’s dads’ balls are always dropping. They’ve got to, if they’re to survive Everest, and multitudinous mall-and-basketball-like scenarios in the post-Apocalypse. That’s right; shit getting real, here.

Fleming’s books also include The Book I Will Write (a hilarious series of letters by a crazy dude to an editor at Knopf), Fearsome Creatures of Florida (exactly what it sounds like, but including Fleming’s brand of funny which is funny), and The Legend of the Barefoot Mailman (a novel of whim and the creation of what else but Florida). What comprises all of Fleming’s writing is his outstanding prose, his sensible ear, his sense of humor. The man knows that, if anything, we must laugh our way to Hades. His godliness is next to our humanness. Or our humannesses conflate in the worlds that Fleming constructs out of language. Have a listen here in the interview I conducted with John (wherein we discuss all manner of animalian monstrosity), and in his story “Chomolungma,” from Songs for the Deaf.

JI: So I saw recently you were posting on Facebook about monsters or something? Are you really into monsters?

JHF: I do love monsters. I grew up on the Universal monsters—Drac, Wolfie, Frankie, and gang. Boris Karloff and Vincent Price were my heroes. I also loved the Godzilla movies. I did a pretty good imitation of the Godzilla screech in elementary school and the lunchroom lady busted me for it. Appreciation of the Godzilla screech ought to be in the pre-employment screening for cafeteria professionals.

JI: Did you see the most recent Godzilla movie? What’d you think of that?

JHF: Just saw it and liked it. While it’s hard to beat the charm of a guy in a monster suit, I thought the new CGI Godzilla looked badass, and the buildup to his delayed entrance was a nice touch, in keeping with the old monster movie tradition. Some of the most realistic city destruction I’ve seen. The human plot did its job, but of course no one goes to see a Godzilla movie for that. Given the military/technology themes of previous Godzilla movies, I found it interesting how the message in this version was that in order to restore balance we have to let the monsters fight it out. Is the movie trying to tell the U.S. something about the Middle East? After decades of misadventures, that may be where we’ll finally end up: back off and let the monsters fight it out.

JI: I’m trying to categorize your stories in Songs for the Deaf. Generally, I hate categorizing anything, but for the purposes of an interview discussion, I guess I’d say that many of them strike me as magical realism. Although there have been white male writers who have written in this style (say Faulkner of “The Bear,” for example) it seems like a lot of folks out there tend to think of MR as a largely Latin American invention, and that such authors are the predominant practitioners of the style. Seems even Wikipedia agrees with this, so it must be true. Does that, or did that, ever give you pause as a writer? Do you feel okay being a white guy who does this stuff?

JI: I’m trying to categorize your stories in Songs for the Deaf. Generally, I hate categorizing anything, but for the purposes of an interview discussion, I guess I’d say that many of them strike me as magical realism. Although there have been white male writers who have written in this style (say Faulkner of “The Bear,” for example) it seems like a lot of folks out there tend to think of MR as a largely Latin American invention, and that such authors are the predominant practitioners of the style. Seems even Wikipedia agrees with this, so it must be true. Does that, or did that, ever give you pause as a writer? Do you feel okay being a white guy who does this stuff?

JHF: To this day, there are writers whose works I love but I avoid re-reading because my first encounter with them was so mind-blowing I’m afraid to break the lingering spell. García Márquez is definitely one of those writers, along with Borges. But I would also include Kafka, Calvino, Bruno Shulz, and Milan Kundera—non-Latin American writers who are sometimes lumped into the magic realist category. These writers opened up possibilities for me and helped me figure out what kind of writer I was and wanted to become. I don’t know whether they’re truly magic realists or not. The only thing about magic realism that everyone can agree on is that García Márquez is the prime example, but García Márquezism is a literary term that won’t catch on.

In the U.S., we have a sort of homegrown magic realism—the tall tale. American tall tales historically featured a deadpan delivery and increasingly absurd events that test the reader’s or listener’s willingness to venture deeper into the fictional wilds. I’d put at least some of the stories in Songs for the Deaf in that tradition. George Saunders’s and Karen Russell’s work might fall into that tradition, too. Really, though, I like variety, and the stories in SFD don’t fit neatly into any single category. Every new story I write is in part a reaction to the one I wrote just before it (or the one I’m currently stuck on), and I’m usually in the mood to try something new in terms of style, tone, form, etc.

JI: You say, “Every new story I write is in part a reaction to the one I wrote just before it (or the one I’m currently stuck on),” and I know that the stories in this collection were written over a period of about twenty years. Do you have these stories in your mind for such vast periods of time, or do you draft and let them linger before revising?

JHF: Having written myself into a corner many times and yanked out a lot of hair, I’ve finally become a believer in setting things aside for months or even years. I’ve abandoned a story in frustration and two years later picked it up again, only to realize I already have an ending or I’ve got two paragraphs to write and the thing is done. It took me a long time to learn this; my inclination is to put on the blinders and run for the finish. Part of what helped me change my approach is the process of submitting to literary magazines. Some of the stories in Songs for the Deaf took up to nine years to get accepted, either because they were oddities, or they didn’t find the right editor, or they just weren’t good enough yet. (I put the complete rejection stats into a facebook note.) The unexpected benefit of waiting so long for publication was that, after each round of rejection, I had another opportunity to revise the story and make it better. Some of the SFD stories were further revised between magazine publication and book publication. And if there’s ever a second edition, I’m sure I’ll revise again.

JI: You’re a professor at the University of South Florida and you’ve written the book Fearsome Creatures of Florida. So it would seem that your proximity to monsters and Latin Americans might go hand-in-hand with your predilection for something like magical realism (if we’re gonna go ahead and call it that). In most monster stories (that is, of the aforementioned Hollywood types), it’s invariably a dude who saves a woman (usually) from said monsters. Is that a role you saw yourself in as a boy while watching these movies? Do you sometimes think of this role when writing your stories today? And lastly, do your students have any good monster stories that you have stolen, or that you’ve been tempted to steal?

JHF: I identified with the monsters. Except for his earliest anti-nuclear movies, Godzilla was a misunderstood antihero. Frankenstein’s monster, in Karloff’s portrayal, is a childlike creature in a too-powerful body. Dracula’s all about unbridled passion. The Wolfman is tortured by the moon. The Creature from the Black Lagoon is madly in love with a woman he can’t have—the beautiful researcher played by Julie Adams. The creatures all had more complexity and emotional depth than the heroes, and what kid can’t relate to an id-ruled, misunderstood monster struggling with body control? Those damsel-saving heroes, on the other hand, lacked the sensitivity to understand the monsters they killed. They didn’t deserve the girl. Or maybe they did, because the women were often no better; they were mainly in need of someone to catch them when they fainted.

In a way, growing up in Florida fed perfectly into my predilection for monsters. As tame as the suburban neighborhoods are down here, you step outside of them and you’re in monsterland. Giant prehistoric lizards and venomous snakes; bushes and vines that shred your calves, seemingly with malice; swarming insects; poisonous toads; patient vultures; sharks stalking the bathing area (I’ve seen the helicopter shots); not to mention the humanoid monsters who gravitate to Florida for easy access to drugs and old people’s money. When I was a kid, my friends and I made elaborate plans to dig an underground fort with an intricate system of tunnels. Every time we tried, we’d get about four feet down into the sandy soil and hit water. Then the sides would collapse. The fort never got dug, and it made me feel I was living on a thin crust of dirt that could collapse any moment into the black depths. A couple of years ago, and not too far from here, a sinkhole opened up in the middle of the night beneath a guy’s bedroom. It took the guy and the bed and everything else in his room. The house—right in the middle of a regular old middle-class suburban neighborhood—had to be condemned, and they can’t even go down there to look for his body because it’s too dangerous. See what I mean?

I haven’t stolen any monster stories from my students, but I’ve been working on a Fearsome Creatures book for kids called Fearsome Creatures of Your Elementary School, so I’ve been visiting the elementary school where my wife teaches and reading some drafts and asking for suggestions. Just about every kid has monster ideas, and I may use some of them. Surprisingly—or not—some of their creations are too brutal and gory to put in the book.

JI: Okay, I definitely want to hear about some kid’s idea of something that’s too gruesome to go into a book.

JHF: We’re talking about creatures who stab your eyeballs and eat off your face and slice up your guts to put on pizza. Kids deserve more credit for their dark imaginations.

JI: And what about your imagination? You have a very funny, magical, flip sense that surrounds much of your writing. How dark do you go—or have you gone?

JHF: Well, in Fearsome Creatures of Florida I’ve got the Mangrove Man, who, if you don’t leave him alone, stabs you with his prop roots and drains your blood. And the Globesucker, who sinks its fangs into anything globe-shaped—oranges, grapefruits, heads. And the Balloon Weed, that lives in sinkholes, wraps you in vines, and digests you nice and slow. And a species of Key Deer that surrounds your car and shoves you into the waves when you’re trying to escape a hurricane. Nothing’s more fun than inventing horrible creatures, especially ones who are seeking revenge on humans for environmental degradation. But mostly I go for the darkly funny satire rather than the out-and-out horror. I would like to write a straight horror story, though, and I might tackle that before long.

JI: What is it about dysfunction—whether in a family, as is the case in “Chomolungma,” or in an individual character, like in Antonio in “Song for the Deaf”—that you’re drawn to?

JHF: What really interests me in those stories (and many of the others) is the struggle to create or sustain an illusion—or, on a bigger scale, a legend or myth. The dad in “Chomolungma” has a sentimental vision of his family, and he’s going to cling to it all the way up Everest. There’s a degree of sweetness to it; he’s all about togetherness, and he’s desperate to bring his family back to the fold—so desperate, it turns out, that to make his plan work he’ll lead them all up Mt. Everest to their deaths.

In “Song for the Deaf,” on the other hand, the narrator, Jeremy Jones, struggles not to sustain a myth but to defeat one—the myth that unfolds around his nemesis, the Magnificent Antonio. Jeremy clings to the idea that Antonio’s beautiful singing voice is undeserved and his acclaim unjust. He obsesses over it because he sees the myth taking shape and feels powerless to stop it. Lucky for him, fate shows up in the form of the deaf girl.

I love these obsessive characters. Don’t we all cling to our illusions well beyond their expiration dates? Isn’t that how we build our identities? And the struggle with illusions has obvious resonance for me as a fiction writer, where my job is to make the reader believe what I’m writing, if only for the duration of the story. It’s an amazing trick, when you think about it, and it can’t really be pulled off unless the writer convinces himself first.

JI: I like that you bring up legend and myth in this last response, as that seems like an overriding theme across the book: the story of a bullied teenager’s ascendance over his tormentors in a basketball game becomes a future generation’s gospel; or the ghost-story-like beginning of “Weighing of the Heart,” as the narrator picks up the floating woman along the roadside. Seems like much of your other published writing also puts a lot of stock in the conceit of legend or myth.

JHF: In the stories you mentioned, I tried to wrap a personal story in myth. The basketball gospel in “The Day of Our Lord’s Triumph” is just one kid’s story on the basketball courts, but it becomes, after the apocalypse, a cultural myth. It gives the kid his ultimate revenge on the high school bullies. Who knows whether Our Lord really won the basketball game or if any of the details are historically accurate? What matters is that he survived and spun the story for his disciples.

For “Weighing of the Heart,” I borrowed from the Egyptian Book of the Dead—specifically the “weighing of the heart” ceremony, in which the deceased is judged by weighing his heart against a feather. He may proceed into the afterlife only if the heart and feather balance on a scale. If they don’t, his heart is devoured by the demon beast Ammit. The narrator of “Weighing of the Heart” is burdened with guilt at the death of his wife, which he believes he caused by his lapse of attention. To atone for this, he feels compelled to drive around in his big V8 (I’m thinking of the awesome ’73 Buick Riviera I used to own). I gifted him a floating girl with a feather tattoo to help him balance his heavy heart. Instead of driving into oblivion, he redeems himself by saving her.

JI: How did that fascination with myth arise?

JHF: I didn’t make a conscious decision to write about myths and legends, but I’m fascinated with the individual and group psychology of them—as well as the feeling they evoke—so it’s something that turns up often in my fiction. When I was a kid, I got obsessed with a Norse mythology book in my elementary school library and would beeline toward its shelf every chance I got. But, you know, I was also obsessed with Where the Wild Things Are. So there it is: myths and monsters; I always had an interest in these things. In my experience, reading or hearing a legend or myth is a communal and timeless act. It allows us to step outside ourselves and feel a sense of awe, like standing on a beach and contemplating the night sky or surveying a cityscape from a tall building. As a grown-up person and a writer, I’ve gotten more interested in the process of making those legends and myths. How does one person’s story become a cultural truth that expresses our deepest feelings about ourselves and the world?