Comfort the Afflicted Food and Afflict the Comfort Food: an Interview with Aimee Bender

03.07.10

It’s June first and I’m headed to Skylight Books, an independent bookstore in Los Feliz, Los Angeles, to hear Aimee Bender read from her new novel, The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake. In an era when independent stores are becoming an entity of the past, Skylight has expanded. It’s evidence that Los Angeles’ literary community is still very much alive, made all the more apparent by the large crowd waiting to hear Aimee read.

It’s June first and I’m headed to Skylight Books, an independent bookstore in Los Feliz, Los Angeles, to hear Aimee Bender read from her new novel, The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake. In an era when independent stores are becoming an entity of the past, Skylight has expanded. It’s evidence that Los Angeles’ literary community is still very much alive, made all the more apparent by the large crowd waiting to hear Aimee read.

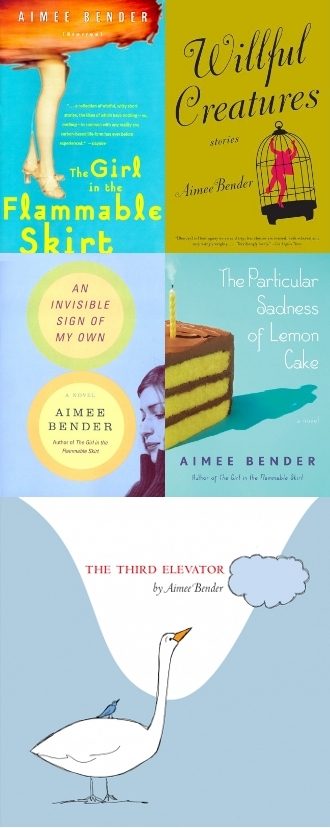

The introduction is brief. A list of Aimee’s books: her two novels The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake and An Invisible Sign of My Own, her novella The Third Elevator, and her two short stories collections, Willful Creatures and The Girl in the Flammable Skirt. I recognize a few graduate students from the University of Southern California, where I took a writing seminar with Aimee. It’s always a little nerve-wracking studying with writers you admire. What if they hate your work? What if the friendly, inviting narrator of their books is actually a reprehensible person in the flesh? It’s been known to happen. But anyone who’s met Aimee Bender knows that this isn’t true of her. If there were an award for the nicest writer, she would be a finalist. As anyone who’s had her as a professor knows, she’s as good of a teacher as she is a writer. Like her magical, strange, and inimitable ideas for stories, her writing advice is so good it seems almost obvious, and yet, I’ve never heard it elsewhere.

Aimee walks up to the podium with that ‘publication day’ glow. She isn’t nervously knocking on the wooden podium and doesn’t look like she wants to disappear into it, although her characters might if given the same situation. She reads a selection from the first two chapters of The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake, in which Rose Edelstein discovers that she has the unique ability to taste people’s feelings in the foods they prepare. Rose realizes this on her ninth birthday, when her mother’s lemon cake with chocolate icing tastes “empty.” Rose continues to learn people’s unspoken feelings, including her mother’s silent loneliness. In a bite, she can locate the origin of every ingredient and subsequently craves the anonymity of processed foods—substances so disconnected from their origins that they remain silent. The novel is a portrait of the Edelstein family, narrated through Rose and her unique insight into the individuals around her.

When Aimee is finished reading from her novel, there is the requisite Q and A session, my least favorite part of readings. Often, it seems that the audience isn’t asking questions so much as making statements about the author’s greatness—followed by the uncomfortable gratitude of the author—or observations disguised as questions, which make the questioner sound insightful without really asking the author much of anything. While there are a few questions on Aimee’s lack of quotation marks in her writing and her sharp dialogue, today’s questions are astute and interesting. People ask her about the germination of her ideas, the selection of foods she describes in the novel, her relationship to Los Angeles. Overall, the reading is a success. Pithy. Sweet. Energetic. Funny. Much like Aimee’s writing.

After the reading, I got to catch up with my former writing professor. We chatted about her writing, her new novel, food, and the Hollywood Farmers Market.

Your writing has been described as magic realism, American fabulist, and slipstream. How do you feel about these labels?

I am more and more interested in the labels as they change. Slipstream is both less specific and more specific. No one is that familiar with it so that’s kind of fun. Fabulism is a very appealing word. When I’m writing, I’m not thinking, this feels more like magical realism or fabulism. I’m not describing what I’m doing to myself in that way. But it’s been interesting and nice to see how the terms keep changing and how there are more and more writers not fitting into standard realism.

Many readers are drawn to your stories and novels alike because they’re not standard realism. How do you come up with the unique ideas for your stories and novels?

I think it’s less for me about how and more about opening up to different ways that stories are told. I’ve always liked strange theater and unusual poetry. I went to a play with a friend last year by Sarah Ruhl where one of the characters turns into an almond. It was so pleasing that she made that choice and to see what that meant. I’ve learned to like lots of other kinds of writing but my first love was for that magical storytelling. So when I’m trying to write about an experience or a feeling, that feels like the most natural way to tell a story.

Can you describe the relationship between your magical storylines and the realistic feelings and experiences that drive them?

I almost think you’re separating them too well. They’re united. I will often start with a premise or a magical concept and then investigate it. Some magical metaphors or images feel ripe with emotional weight and some don’t. It’s sort of like there’s reality in there already or there isn’t. I’ll often have false starts and the false starts are a magical idea that doesn’t have any depth. Those just fizzle out. The ones that have some depth to them, I want to keep writing.

How does the depth of the ideas relate to the stories you write as short stories and the ones that become novels?

It really feels like short- and long-distance writing. Short stories will grow for a certain distance and then end. With a novel it’s more about hitting upon a voice or a character. I don’t know that it can work as a novel, but it doesn’t feel that it can end soon. There’s this feeling of a lot of questions marks. There has to be some big unknown in the act of writing that fuels the book. There are plenty of unknowns in story writing, too, but with a novel I don’t know what will last the length of the book until I’ve been working on it for awhile.

So what was the big unknown in your new novel, The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake?

I established the food stuff and then I didn’t know where to go. I knew it needed to shift—that the food was still going to be important but that something else needed to happen that wasn’t going to be about food. That was the part that was groping in the dark for awhile.

But food continues to play a prominent role throughout the novel. And family does as well. Is food something that has played an important role in your family?

I love food, but I was a very picky eater as a kid so I came to food slowly. And I come from a warm Jewish family and I think most warm Jewish families are oriented towards food. My grandmother was an amazing cook and would make all the classics.

Do you like to cook? Do you bake?

I really like cooking, but I don’t bake much. I like trying out new things and finding recipes. I got morel mushrooms this week at the Hollywood Farmers Market. There’s this new mushroom stand called, The Fun Guy. It was so fun to see what you do with them.

So did you discover anything about food or cooking through writing this novel?

I enjoyed it as an excuse to do more food reading. I took a couple of cooking classes that felt like research. It was so enjoyable to learn about some of the basic chemistry of food. Cooking is chemistry and there are so many wonderful food writers. There’s a quote in the beginning of my novel by Brillat-Savarin. His book The Physiology of Taste where he just talks about every aspect of eating in France hundreds of years ago. Here’s a little taste of the chapter titles—salt, death, influence of smell on taste, the pleasure of smell caused by taste, theory of frying, differing kinds of thirst, inconveniences of obesity. He was just someone who took his eating so seriously and would breakdown as many elements of it as he could. I also love all the Michael Pollan stuff.

In the novel, the protagonist, Rose, has the ability to understand people’s feelings through the foods they make. The first cake Rose can feel feelings in is a lemon cake with chocolate frosting, which is fairly unusual. What made you decide to choose this cake?

It just happened that way. I was thinking of a kid’s point of view, that a kid is going to want a little bit of everything. And I wanted the sourness of lemon, not consciously, but the lemon is more complicated than just chocolate or vanilla cake. But, to be honest, I didn’t realize what a taboo it is to have lemon cake with chocolate. The book’s been out a week and I’ve already heard many people saying, ‘This does not happen.’ A chef told me yesterday that the reason is that they’re both so strong, they compete as flavors. But that’s okay. Let them compete.

Did anyone tell you that be fore the book came out?

fore the book came out?

They didn’t. But I don’t think I would have changed it because I think there’s a discord or dissonance to it.

I also noticed in the novel that you have a lot of names of different restaurants and neighborhoods in Los Angeles. Did you explore new restaurants as you were writing to figure out what Rose would like?

It more runs parallel to an interest I already have. I loved going out to eat and then using that as a base for where she might go and for thinking about L.A., the diversity of food, and [LA Weekly’s Pulitzer Prize-winning food critic] Jonathan Gold’s map of L.A. eating. What a great range there is!

I was really interested in the fact that you set this novel in Los Angeles. Your first novel, An Invisible Sign of My Own, had a strong sense of place, but the place wasn’t identified. Why did you decide to define the location in this novel as Los Angeles?

I wanted to write a little bit more about L.A. I’ve lived here a while and I grew up here. So it’s a city that interests me. And it interested me too to write about it not as a film city. It has been gratifying because a few people who don’t know L.A. read the book and said it made the picture of it in their minds feel different. We see a lot of the city on TV and the movies, but we see a certain Los Angeles but maybe not the daily L.A. There are neighborhoods and you can walk. People ride bikes, take the bus and go on hikes. It’s just a big vibrant city with a lot of sprawl, but quite a bit of charm.

The feelings Rose tastes in food are usually subconscious or unspoken. Can you talk a little bit about the role of the subconscious or the unspoken in the novel?

I’m very interested in that realm. I know quite a few therapists. There are a couple in my nuclear family, many more in my extended family. The whole field is really interesting: the classic idea that there are a lot of feelings that are under the surface of everybody and they’re not known to the people around them.

This certainly seems true about Rose’s family, the Edelstein’s. Can you talk a little bit about the role of the family in the novel?

It is a novel about a family. Years ago, I read a quote in a psychology book on family systems about how sometimes children are acting out the conflicts of their great-grandparents. And I thought that was amazing and frightening and fascinating because we may not even know. We can track certain things to our parents and grandparents. So a family is a cross-section in time of a group of people who are bringing ancestry and temperaments and psychologies. That’s so complicated and beautiful and ripe for drama. That’s why what feels so crucial to the book is not just Rose, but Rose’s access to other people. What they are not sharing. What that has to do with how they’re living their lives, and how that affects everyone around them.

I think this is interesting because something that came up in this novel and in your last novel and in a lot of your short stories is that the primary characters don’t have very many friends, at least not present on the page. Does not focusing on friendships as much allow you to have better access to the family?

Balance is not where I’ll throw my focus. There’s something about pushing life to the extreme. It’s the way people will draw on a balloon and when it’s blown up it will suddenly become clear what the shape is but when it’s not blown up, you don’t know. So there’s something about making that shape really obvious that lets me dive in and look at the nuances. I actually love writing about friendships too, they’re another incredibly interesting territory. For the novel it felt a little more streamlined to not get into that.

Was it difficult to write a brother-sister relationship since you grew up with sisters?

It was liberating. It’s easier to investigate because, if there were a sister, I might worry that it looked like one of my sisters. There’s something nice about writing about a situation different from my own.

Readers often try to see the author in the characters. How much is Rose like you? Do people try to make connections between you and your work that aren’t there?

I think anything in first person invites people to think the character is me. There are elements of her that I relate to, but she’s not me. She’s probably a mix of a lot of people. There is something liberating about it being strange fiction. It does give me some space. One of the first people who read an early draft asked, ‘Can you do that, with the food?’ That was so great. He was half kidding, but he wasn’t fully kidding. I felt glad that he thought it was possible, because he’s a very rational guy.

So how much revision do you do to your work?

I’m always reading over scenes and going back over things. It’s a lot. I’ll read over a scene many, many times if I feel continually drawn to it. In rereading a scene I can discover both what I want to change and where I want to go next. There are several levels that the words will sit upon on the page, and you can feel when the word or a sentence has really earned its keep. And you can feel when a sentence feels thin or like a throw away. Part of my work as a teacher is to comb through the story and find sentences that have authority. And that’s what authority means to me—I want to read that sentence.

———————————————————————————

Purchase a copy of The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake here.

Related Articles from The Fanzine:

Aimee Bender, Sam Lipsyte and Dana Spiotta talk about their favorite albums

Amy Meyerson on Tolstoy and John Krasinski’s Hideous Men

Pasha Malla interviews Madras Press publisher Sumanth Prabhaker