If You Give Enough Helper Monkeys Enough Typewriters: An Interview with Madras Press Publisher Sumanth Prabhaker

29.03.10

Amid all the current talk of the flailing publishing industry, it’s nice to know that there are still publishing projects that prioritize stories before sales, and books before some vague idea of the vast, digital future. Madras Press, the brainchild of Sumanth Prabhaker, provides a home for those “clumsy, ill-fitting stories,” whether in length or content, that are “made perfect when read in the simplest possible way”—which is to say individually bound, in beautifully designed and unadorned little books that might not be able to find a home anywhere else in the world.

Amid all the current talk of the flailing publishing industry, it’s nice to know that there are still publishing projects that prioritize stories before sales, and books before some vague idea of the vast, digital future. Madras Press, the brainchild of Sumanth Prabhaker, provides a home for those “clumsy, ill-fitting stories,” whether in length or content, that are “made perfect when read in the simplest possible way”—which is to say individually bound, in beautifully designed and unadorned little books that might not be able to find a home anywhere else in the world.

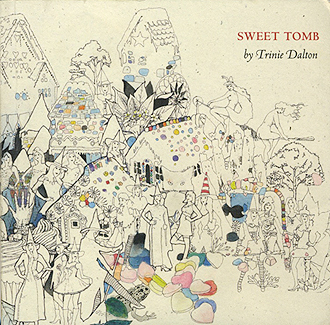

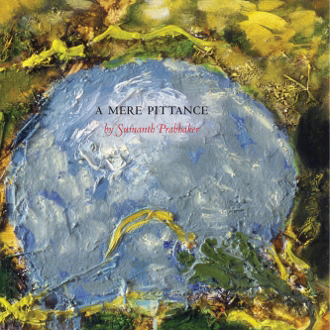

Additionally, Prabhaker has adopted the mandate of donating all the proceeds of the books to charities of the authors’ choice, a choice that suggests that Madras Press is blazing new artistic and altruistic ground of its own. Following the release of the first four Madras novellas (Aimee Bender’s The Third Elevator, Rebecca Lee’s Bobcat, Trinie Dalton’s Sweet Tomb and Prabhaker’s own A Mere Pittance), The Fanzine spoke with publisher and writer Sumanth Prabhaker about how he got Madras Press off the ground, his thoughts on publishing, and what he’s got planned for the future.

How did the idea for Madras Press come about?

The initial idea was just to publish a story of mine, because at eighty pages long and with no exposition, it didn’t seem worth trying to pester an established publisher about. And maybe more importantly, it wasn’t the kind of story that would really benefit from being marketed as a trade book, with blurbs and a prominent barcode and all the other non-story stuff that gets packaged into most books. That decision created a lot of limitations for me—I wouldn’t be able to distribute the story widely, or rely on someone with actual knowledge and experience to do a P&L [Profit and Loss] form—but it also freed me from retaining a lot of the aspects to commercial books that don’t really have any place being attached to a story.

It wasn’t until after I’d come up with the model for the shape and size and layout of the book that I began to hear about other people who had stories that might benefit from a similarly customized format. That was probably part of the attraction, or at least part of what convinced the other authors that it wouldn’t be a horrible idea to send their work to a tiny new publisher—that the format of the books fits the content, and not the other way around.

Why channel the proceeds to charities, rather than to the authors?

When I was just beginning to put this project together, the only book I could count on being able to publish was my own, and it just seemed to me like a nice way to do things. I’d never thought of my stories as commercial products, and I don’t think they’d perform very well against trade books in competing for people’s money. Or at least I don’t like to think of them in that way.

All three of the other authors in our first series are extraordinarily talented and very well respected, and would have no problem selling their stories to anyone they like, so I imagine that this kind of model must have appealed to them as well. And I think part of what makes it an appealing invitation is the amount of control the authors are afforded over the company. Publishers may know a few things about binding and distribution that writers may not necessarily know or care about, but it’s against their best interest to exclude writers from these kinds of decisions. It only makes sense that everyone involved should have some say in how the company’s finances are channeled.

All three of the other authors in our first series are extraordinarily talented and very well respected, and would have no problem selling their stories to anyone they like, so I imagine that this kind of model must have appealed to them as well. And I think part of what makes it an appealing invitation is the amount of control the authors are afforded over the company. Publishers may know a few things about binding and distribution that writers may not necessarily know or care about, but it’s against their best interest to exclude writers from these kinds of decisions. It only makes sense that everyone involved should have some say in how the company’s finances are channeled.

Are you involved at all in helping choose the charities, or is entirely up to the authors?

My involvement in choosing the beneficiaries doesn’t extend beyond my own book; each author has selected her organization and then approached me about it. The financial stuff is pretty simple: once we’ve made back the manufacturing costs, everything else is donated. The amount of revenue generated depends on whether the book has been printed as a limited edition or as an ongoing title, and the proportion of direct sales from our website to sales at local bookstores.

How have the books been doing?

The books have only been out for three or four months now, and since we’re not spending anything on marketing, we’re relying on slow and steady sales, rather than the initial surge and subsequent disappearance that happens to most books in bookstores. I’m expecting the other three books to sell out within the year, and mine maybe in the next year. The charities are very excited, but nobody’s expecting this project to pay the electric bill. We’ll be lucky if each book can generate two or three thousand dollars after recovering the manufacturing costs.

Your business model is certainly unique, but how are the books themselves different from work being published elsewhere?

Part of it has to do with the length of most of our titles; the format of our books requires a minimum length that’s slightly more than a typical short story, and a maximum length that’s slightly less than a short novel, and there aren’t many other companies actively seeking new material with these guidelines (despite the abundance of really good material out there). But I also think a publisher can ignore a story by packing it into a collection with ten or fifteen other stories and making no effort to distinguish or call attention to any of them in particular; or by selling it to a magazine that’s going to print half of it together and then hide the other half of it at the very end in small type; or even just by publishing it in a format that doesn’t suit the content.

I remember reading an interview with George Saunders somewhere, and he said something about wishing that people would close the book and set it down every time they finished one of his stories, instead of continuing on right away to the next one, and I remember thinking how silly it was that someone as smart and accomplished as George Saunders would have to go out of his way to apologize for the manner in which his stories were packaged, just because someone at the publishing company decided it would be better to follow industry tradition than to pay attention to the stories and find the right way to treat them. It seemed like kind of a shame to me.

Do you think story collections undermine the individual power of each story?

Do you think story collections undermine the individual power of each story?

I think it would be a mistake to try and name one specific ideal way to read stories. The goal of this project is just to help perpetuate a reading experience that’s more focused and less preoccupied with commerce; not because all books should be like ours, but because a few of them aren’t and should. There are plenty of writers whose work would suffer in this kind of format—David Foster Wallace’s short story books, for example, are all very attentive to sequencing, and excerpting from them would risk upsetting the balance he seemed to work very hard to create. And I find it to be rewarding to read Barthelme’s stories together, kind of like going to an art museum and going from room to room.

However, I don’t know if all short story authors are as acutely aware of the physical products they’re creating. Sometimes you’ll have a little suite of two or three stories that go together, and then they just get inserted somewhere in the middle of a big collection for no good reason. Sometimes a literary journal or magazine will put your story between two poems because they don’t want two poems in a row. In those cases, I’m not sure the form and layout are benefiting the content. Sometimes, in the case of someone like George Saunders or Flannery O’Connor, it can be very tiring to get to the end of a story, and you need a little time afterwards before you head into the next one. I wouldn’t say that their writing is less than ideal just because their books don’t reward a cumulative reading experience, just as I wouldn’t say that Brief Interviews with Hideous Men is less than ideal because it doesn’t excerpt well. (It does excerpt well, though, of course, but maybe not every page.) I love the idea of stories in conversation with one another, but not all of them may feel like talking all the time. It’s a mistake to fault a writer for producing either kind of story, and it’s a mistake to force that story into a book with inherited specs just because that happens to currently be the format the supply chain prefers.

Might electronic publishing also offer an alternative to books as commodities?

I start sounding dumb when I talk about e-books because they’re not something I’ve put very much thought into. I guess I like how freed they are from the conventional price structure of printed content. I like it when someone puts something up for sale online, and consumers have to wonder whether the price is worthwhile or not; even if it can sometimes feel like a crass discussion, it’s much better than just assuming that all perfect-bound books are worth fifteen dollars and all case-bound books are worth twenty-five dollars. Since the delivery method is so much more direct, it’s supportive of ventures like Electric Literature and Flatmancrooked, whose consumers are forced with each purchase to re-assess the relationship between their wallet and a particular kind of content.

Do you have any plans to do anything electronic with the Madras Books, or is it important to you that they exist on paper?

Do you have any plans to do anything electronic with the Madras Books, or is it important to you that they exist on paper?

I place a lot of value on the experience of finding a book in a bookstore, and on the feel of paper, and the ability to put a book in the mail or in somebody’s hand. E-books are great for the kind of consumer who’s mostly interested in the words of a story, but I’ll always be happy to pay more for that other stuff. Until there’s a way to evoke or at least make me forget about those feelings, I doubt we’ll have much of an online presence.

I’m sure this is just a matter of me being slow to catch up with everyone else. In twenty years, when books are gone and we’re all telepathic or whatever, I’ll probably be clinging to Twitter as the last method of conveying real human emotions, and no one will be there to read my tweets.

Do you think books might have lived out their capacity for social change?

I just started reading Howard Zinn’s history book, and as long as that’s in print, I don’t think there’s any reason to doubt literature’s capacity for social change.

But what about this trend we’re seeing in literary culture that shies away from socially engaged content, yet writers are becoming more and more active altruistically? (Madras Press seems like a perfect example.)

What’s happening now, I think, is the publication of more and more writers young enough to not have any hope that their books will be any reasonable source of income. Whether or not that’s a good thing is another discussion, but it seems very much to be the case; with the declining interest from large publishers in acquiring or at least in marketing new titles comes a declining expectation that my book is ever going to be read by more than a dozen people, which further privatizes the writing process. And so more and more books are being written with only the stories in mind, rather than with a hypothetical mass response to the stories. Social change may have outlived the million-copy book run; it’s now the commerce of blogs, and books are free to be whatever they feel like. But as long as there are readers and writers as generous as the 826 people and the Concord Free Press, there will always be a connection between literature and altruism, whether it’s direct or not.

What’s coming up for Madras Books?

We’re hoping to have the next batch of titles out by the end of the summer, but it may not be until Christmastime. For now the only one I can officially announce is a book by Andrew Kaufman, the author of a very sweet and kind of weird novella called All My Friends Are Superheroes, and, more recently, The Waterproof Bible, which was just released in Canada. We kind of crossed paths in the dark, as I wrote to his agent to introduce myself, unaware that he had already ordered our books, and we both wondered how the other person had heard of us. The book is going to be called The Tiny Wife, and it’s going to benefit Sketch, an art studio in Toronto for homeless youth.

______________________________________________________________

Order books from Madras Press here.

More on Trinie Dalton’s Sweet Tomb.

Related Articles From The Fanzine:

Trinie Dalton’s short fiction and small press reviews