Borrowed Furniture: Poetic Failure and Gift Etiquette in Mike Young’s Sprezzatura

07.10.14

Sprezzatura

Sprezzatura

by Mike Young

Publishing Genius

132 pp / $14.95

“I do not think I really have anything to say about poetry other than remarking that it is a wandering little drift of unidentified sound, and trying to say more reminds me of following the sound of a thrush into the woods on a summer’s eve– if you persist in following the thrush it will only recede deeper and deeper into the woods; you will never actually see the thrush (the hermit thrush is especially shy), but I suppose that listening is a kind of knowledge, or as close as one can come. “Fret not after knowledge, I have none,” is what the thrush says. Perhaps we can use our knowledge to preserve a bit of space where his lack of knowledge can survive.”

― Mary Ruefle, Madness, Rack, and Honey: Collected Lectures

A professor in college told me poetry was about passionate almosts: moments when a desired object or idea is glimpsed but not quite fulfilled. Often, language can offer us a means of access to an experience that is otherwise deferred or denied to us altogether. Of course, not all poems are about explicit loss. Poetry is always an act of preservation, though: it exists as proof of an attempt to distill or replicate something (an experience, a feeling, a moment, whatever) otherwise fleeting, and always acknowledges remorse for the lost original/“real” form. So, all poetry comes out of failure, imagining what we cannot have or commemorating what we cannot hold on to. Language is everywhere and nowhere: it houses placeless desire. Words prove that not everything we want is possible – they pathologically straddle and fail to cross the gulf between what we desire and what is possible to us – and are both, and are neither.

Wikipedia: Sprezzatura [sprettsaˈtura] is an Italian word originating from Baldassare Castiglione‘s The Book of the Courtier, where it is defined by the author as “a certain nonchalance, so as to conceal all art and make whatever one does or says appear to be without effort and almost without any thought about it”.[1] It is the ability of the courtier to display “an easy facility in accomplishing difficult actions which hides the conscious effort that went into them”.[2] Sprezzatura has also been described “as a form of defensive irony: the ability to disguise what one really desires, feels, thinks, and means or intends behind a mask of apparent reticence and nonchalance”.[3]

The word has entered the English language; the Oxford English Dictionary defines it as “studied carelessness”.[4]

There’s a little ugliness that goes with the word irony, though maybe it shouldn’t. What I mean to say is this: often, art functions in spectrums that turn in on themselves – that possess a circularity, and often culminate in ‘opposite’ aesthetics touching, interacting, or occurring simultaneously. The achievement of heightened abstraction is its unique realism. Irony is felt most not as device or hoax – but rather, what we candidly speak through it.

“To make someone weep and still have that

playing as you watch someone else make a courageous

estimate in the crosswalk.”

(“You Must Motherfucking Change Your Life” pp. 4)

At its most lovable, Sprezzatura is distracted and deflective. Its language wrestles with the ecstatic disorder of living, or, as the author puts it:

“None of us have that “all they needed

to do was talk with each

other” like they have at the end of the episode.”

(“Nuns of the U.S.” pp. 34)

True to its title, the playful craft of Mike Young’s poetry does execute a kind of trick: progressing from levity to solemnity and back, creating distance only to later extinguish it. Its poems conduct a series of experiments; they bring us closer to what we love and the absence we feel when we cannot possess it.

Sprezzatura has a simultaneous quality to its lyricism: while some poems end by beginning a new thought, question, or conversation at the last minute, others remind us how panoramic and overlapping our experiences are simply by naming one. (“The page with the lyrics you searched for/starts to play a different song.” (“Turn Right at The Bridge You Make By Lying There” pp. 11))

I am in the process of moving to Los Angeles as I read and write about Sprezzatura and turn everything it says it into a metaphor about how shitty I am at cleaning an apartment. Things start falling apart. At one point, I stay up all night corralling my belongings into the North East corner of my bedroom. I find myself spending most of my time in the kitchen, hiding from these… physical manifestations of my practical shortcomings. My cat is making noises a cat shouldn’t make. I realize that if I move the kitchen chair to this one weird corner I can obtain weed food without getting up. It’s not great. I keep Sprezzatura on the table to remind myself of a marginally saner ‘actual life’ I hope to one day return to.

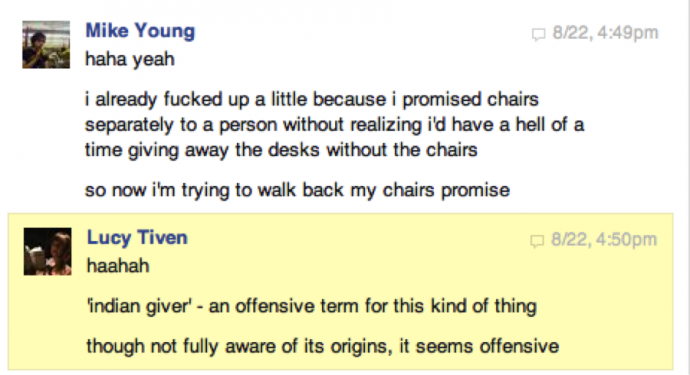

As I begin the review, Mike and I are both amidst Craigslist dealings. My bedframe is getting taken apart. Mike is – with some attenuation – trying to go back on an offer for a free chair. We chat while separately trying to take apart or dispense of our belongings in different browser tabs. I am really into the book and have some ideas for the piece, but mostly, I am grateful to speak to someone living outside the kitchen. It’s nice to hear that I’m not the only one plagued with cumbersome furniture.

It turns out that I have “Indian Giving” a little wrong: I’ve always thought it meant taking something back at the last minute, but the consensus is that an Indian Giver gives as part of an implicit trade for an item of equal value. It’s an interesting idea despite obvious issues with the terminology. What does a gift mean for and about the giver and recipient? Do gifts have anything to do with fairness? How does who we are figure into what experiences and objects are granted to us and how we should treat them?

While it is quite entitled to believe you deserve more than everyone else in the universe, to think everyone is equally deserving of nothing is to exist at a far pole of nihilism that is just as problematic. Most of us fall somewhere in the middle – we are concerned with equality, but also strive toward some idea of perceived specialness. How much/what does anyone deserve? And why? Are emotions gifts? Is language/art? Isn’t it annoying when someone tries to split up an appetizer based on how many pita triangles each person consumed? Does anything in the universe have less heart than a rigidly conducted office Secret Santa? Why can’t people just share and go with the flow, man? What does any of this have to do with Sprezzatura?

“To be present in the world doesn’t make you/a present to the world” begins “You Must Motherfucking Change Your Life” (pp. 4). Like this, Sprezzatura navigates, rearranges and refracts the precarious naiveté of being human into something fun and worth aspiring to. It confesses, plays, and sneakily philosophizes, parsing through uncertainty.

“Often I throw a tennis ball against the wall and hope

the people downstairs believe more people exist

above them than really do.”

(“Rule Number One of Everything” pp. 6)

Sometimes, when I want to feel abstract hope I think about pre-industrial labor–or, more specifically, the people who built cathedrals in the middle ages. Can you imagine spending every day working on such a tiny part of something that wouldn’t be finished for over a hundred years? And being, like psyched on it? Not thinking what am I going to get? For the most part, I can’t. But I’m trying to. That’s my valley girl existentialist spiel. The world isn’t an ATM. It isn’t there for us to use, but we are a part of it. Keep that in mind. Mike says this a variety of better ways throughout the book and this particular poem:

“This plan to prove the world strange, it reminds me of

shooting people in the feet and shouting Dance! Howdy

partner. The world ain’t a stranger, it’s a body.“

Of course, the plan takes form of an anti-plan. Or, to use the gift metaphor, the poem fluctuates between give and take – it confesses, observes, renounces, and offers praise. Things are tinged with a soft, borrowed quality; we are permitted access to the world, knowing we cannot take it with us when we leave. The poem could end this way: by announcing deficiency, but instead, it does the opposite, giving (thanks and praise) rather than lament.

“Thank you for letting me crash

with you. Now I want to praise unusual partners,

such as fear. Let us talk of all that proves.”

I like the idea of the world as a friendly couch to crash on rather than a final resting place, though the second person also functions within the smaller realm of the poem at the same time: by the end, what announced itself as a plan is a faint conversation between strangers – and continues, even after we turn the page.

The pace and motion of Sprezzatura reminds me of the story of Scheherazade: its witty, complex weavings carry us through the book and transport its speaker past any single despair, want, or image. Often, these poems begin with a question, only to later renounce the question/answer format, or praise the ponderous sensations that unanswerable questions inspire in us. Ultimately, even the answers we are given unravel into image. Information is abandoned in favor of the fleeting, luminous instability of sensory experience.

“A poem is a lot of white feathers

that have been ruefully clumped to soar, totally not

sure why they’re doing that, flying, so why not for

the sake of uproar?”

Why not? Beauty, like everything else, occurs through unplanned subversion: the self-disrupting language of Sprezzatura maneuvers delicately between earnest and flippant. Nothing knows what the hell it’s doing and it’s wonderful (isn’t it?).

If the book itself is a “sprezzatura” device, it serves the author as much as it does audience. There are moments when we almost understand things. Then, it turns out to be an echo, or it slips away. Or anything else. That’s all I want from poetry: that moment when something is so close to crystallizing, that for a second you believe it actually won’t go. Then, it does, and you’re back to thinking about an ecologically sound way to dispose of your dead cable box, or you can’t not imagine neighborhood youths being cruel to your furniture and why does it actually hurt you? I like art because I like being taken away from all the banal shit I feel bad about it. Like most of the art I admire, Mike Young’s Sprezzatura doesn’t take me to a single specific place or move like a safe or viable vehicle. Its poems revel in inconsistency; they move like weird little ships. They keep changing direction, but it’s never annoying or difficult or the same as the time before. No one is thrown overboard or gets a maritime disease. The passengers are happy, and ready for a change, and each time, it feels like going in the right direction.