Book Album Book: The Creaking of the Word

04.04.19

Part 10,[1] in which we go deep into the surface. Previous installments can be found here. Read in any order.

We listen for the possibility that singing returns us to the sense of language in sound. Definition, then, is to be resisted. The lyric sheet is a discarded script. What we hear is as important as what the singer might mean—which is not to say their intent is insignificant. The song is a field we enter with other singers, other listeners. This might seem like a curious way to approach the notion that albums are literature. Perhaps, though, it brings us back around to the question of what sort of literature albums (and the songs or tracks that make them up) might be. If music is an art form (or medium) that is distinct from the novel, for example, this is a matter of what different media can do, and how they can do similar things differently. It is difficult for language-based art forms to reach a level of abstraction on the page that they can much more easily attain in aural performance. Just so, a written piece becomes something else when it is read (or sung), even if there is a high level of fidelity to the text. Expressive phrasing does not necessarily correspond with so-called proper enunciation, and this is material to what the sung song can do.

Good lyrics might be a matter of material that lends itself to effective and affecting phrasing. We might also desire compelling phrases to emerge in that phrasing, even if we don’t require the lyrics as a whole to operate on a strictly semantic level. The right words for literary meaning might not come through in song, just as banal or ridiculous lyrics might be transformed into sublime or transporting effects in the mouth of a singer, as arranged with other music. Singing is not just the transmission of lyrics, but their translation into the music, their braiding into the song. If the voice is an instrument, singing is not language, but sound—vibration and wind. If vocals remind us too much that they are language, or not enough that they are sound, the spell of the song might not transform us into aural bodies. And we want to be music, to move with it and be moved by it, not just stand before it.

Lyrics don’t need to be poetry because they are essentially sung. Whereas poems are the music. Lyrics can be music but don’t have to be all the music. They rely on being carried by the tune (and the body). Poems can sing when sung but do not need other instruments. This is the difference but also the connection. Lyrics can be poetry too but are another mode, modular. Again the connection: modulus, Latin for measure, where words are the measure of the line.

Writing about and with music is distinct from conventional interpretation.[2] To write with an album is interpretive, but interpretation invites association and reference to intertexts and to the listening experience itself. We distinguish this extended technique from a conservative sense of interpretation that requires us to discover only or primarily the musician’s experience or projection of the songs. So Cat Power’s “Black” might speak of a particular relationship or type of relationship, while we might run off with the Angel of Death at the start of the song, and read all dark passages on those terms. If this is misreading, it is productive, and true to the experience of listening.[3] Furthermore, experienced and empathetic singers and songwriters know their songs are not their own, or are not only their own. They let us into the song as much as they give us access to their psyche. More so the song, perhaps. We go to the song and the song goes to us.

Side 1

And it’s so long before my futures come.[4] The last song on side 1 of Jessica Pratt’s Quiet Signs is “Poly Blue.” It’s a track that folds into the tapestry[5] of the album as a whole, and it’s the moment where we sigh into the spell of the album, being there in having been there all this side. So when we turn the record to “This Time Around” we are also already there. The tracks lay over one another. We echo through the corridors. It is like showing up in the room on the cover of the album, where you are standing where Jessica Pratt is standing, only you are also lying on the bed where you are standing on perpendicular palimpsest with yourself, having emerged from where you drifted off. You flicker between asleep and awake, yesterday and tomorrow, there and there.

Side A – D

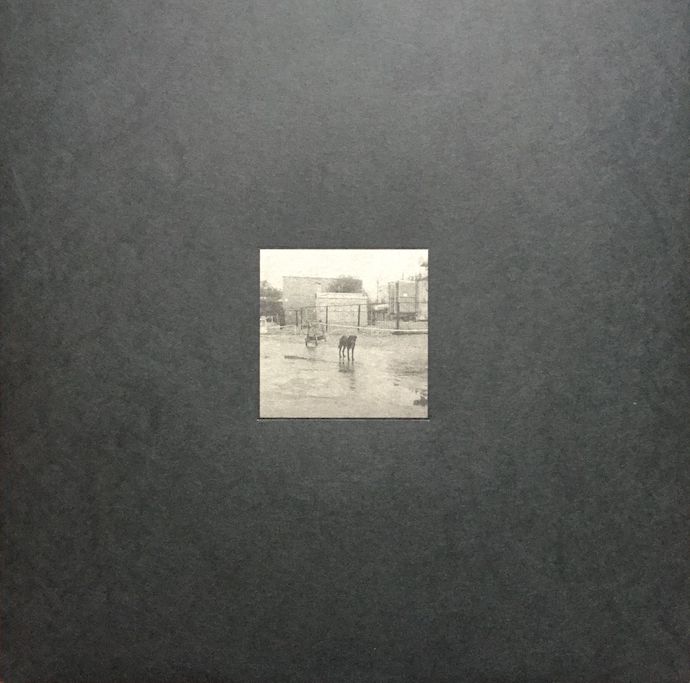

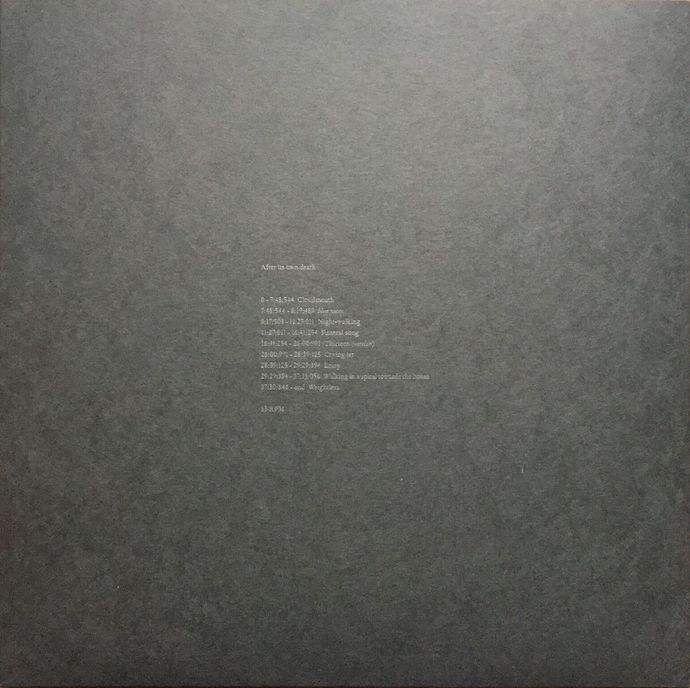

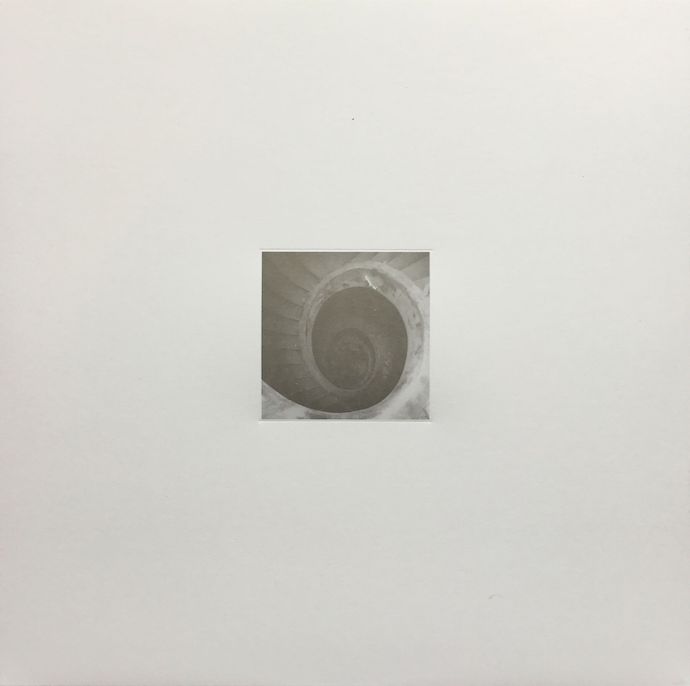

We have a different relation to a book on tape than we do to a book on paper. So the ebook is not just a different format, but a different medium. The type is no longer set, we use different reading gestures, and our interface to literature is transformed. The vinyl edition of Liz Harris’ Nivhek double album After its own death / Walking in a spiral towards the house embodies (and houses) this material transformation, inviting us to experience the album in a number of ways that are markedly distinct from the digital editions on streaming services like Bandcamp and Spotify. Whereas the digital track listing is divided into four pieces that recall a double-album vinyl sequence (“After its own death: Side A” through “Walking in a spiral towards the house: Side D”), the vinyl pressing includes letterpressed sleeves that further articulate the numerical and linguistic sequence. The first LP begins with “0 – 7:48:544 Cloudmouth” and concludes “37:30:846 – end Weightless,” and indicates that the record be played at 33 RPM. Meanwhile, LP2 begins “0 – 3:14:509 Night-walking” and concludes “12:59:510 – end Walking in a spiral towards the house” along with an indication that the record be played at 45 RPM[6] and the words, “Are you riding all alone in the sky? Or have you found some quiet time…”[7] LP1 is divided into nine compositions with unique titles. The inner and outer sleeve are black (the outer sleeve inset with a photograph), and the vinyl label is solid black without any lettering. To discern side 1 from side 2, neither of which have differentiated song regions in their grooves (nor is there an indication of side 1 or 2 on the track list, if that’s what it is), we have to check the etched serial numbering in the runoff groove. 181852E1/A is also etched with the words SO DOES THE ECHO OR REFRAIN; 181852E2/A is inscribed with the words TRUST OR PAUSE THERE.[8] LP2 lists four compositions on a separate white sleeve (with inset photo) that matches the inner sleeve and blank label. One side is etched 181852M3/A and IN THE BODY – while the other side is etched 181852M4/A and SO HARD FOUGHT. Each sleeve contains a 5×7” letterpress lyric card: the black one is “Cloudmouth,” the first composition listed on LP1; the white one is “Crying jar,” the sixth composition on LP1 (another gesture to tie and conflate the sides).

What are we to make of this? How does the sequence help us navigate “tracks” that aren’t tracked on a medium that does not give us a time cue readout (much less one that runs to seven digits)? We are presented with an annotated analog (and analog annotated) synesthetic listening experience. We receive the music as collaborative, fabricated object. The act of listening is staged as a series of gestures (e.g., removing records from sleeves, parsing materials and indications, flipping records, changing speeds) in concert with the composition, performance, and recording of the music.

We might be hard pressed to match the inserted lyrics with Harris’ vocals on the records, or even locate voice in the mesh of vocal and nonvocal sounds.

We are invited as well to disregard all printed or etched media and listen to any side at any speed.

Side 2

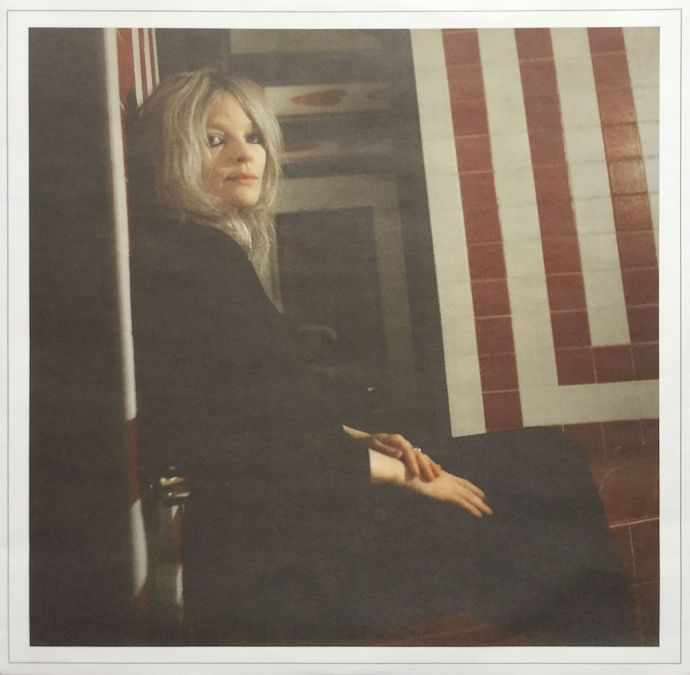

The album opens with “Opening Night,” a wordless piano figure haunted by a prelinguistic caress. When lyrics arrive in the next track, “As the World Turns,” which like the opening track of side 2 (“This Time Around”) evokes a spinning (and flipping) record, language will be overcome by modulated oohs. Likewise, vocal reverb will carry the lyrics to lower registers of meaning, while we float above the turning world. The inner sleeve shows Jessica Pratt seated in the back corner of the room on the outer sleeve, regarding us regarding her, backed by shadow. On the other side is a lyric sheet, also with a single-line border, which lists only the words.[9]

The second song on side 2, “Crossing,” has words but leaves no mark on the lyric sheet (which notes “All songs written by Jessica Pratt”), though Al Carlson’s piano is credited (as is Matthew McDermott’s piano on “Opening Night”). The third and penultimate track on the second side is “Silent Song,” and is not silent, though it is quiet. The final song is “Aeroplane.”[10]

————————–

[1] The title comes from a libretto, “metalecture,” out jazz composition, and speculative literary construct in Nathaniel Mackey’s essential Bedouin Hornbook.

[2] Just so, we resist perceived expectation (via prominent strains of music criticism) to describe instrumentation and the sound (vs. the sense) of sound—not that we avoid it entirely, but we try not to rely on it: If you got ears, you gotta listen, says Don Van Vliet.

[3] We distinguish this from literary misprision in that we are not talking about an anxious relation with musicians or forbears, but rather a collaborative and ongoing proliferation of meaning, generation of pleasure, and further complication of the sound/sense dynamic.

[4] Or before my future’s come. We could check the lyric sheet, but prefer this ambiguous version of “As the World Turns.” We want both.

[5] as we fold in time, which Quiet Signs tucks away

[6] which we forget without consequence

[7] as though and because time is a place we might go, ourselves to find if not to find ourselves

[8] Meanwhile, we might lose track and flip the record twice or more.

[9] and credits (no oohs &c.)

[10] which takes us away