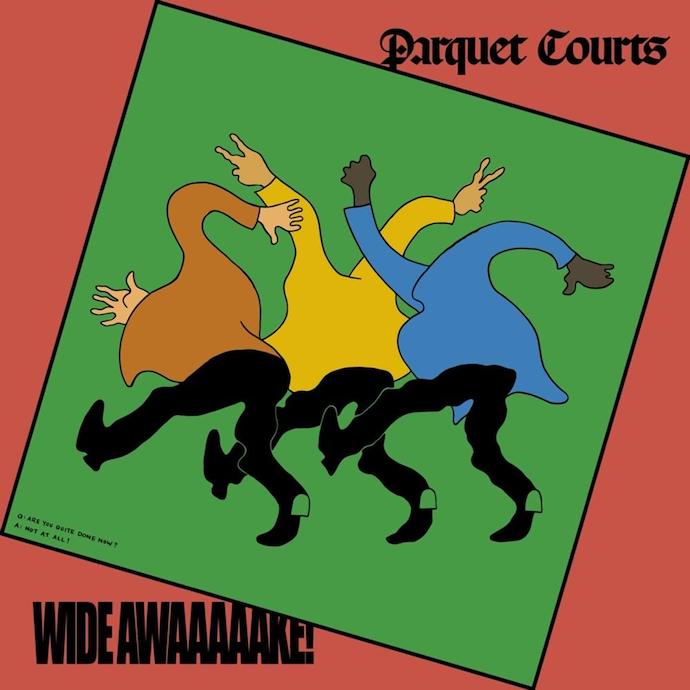

Book Album Book: Parquet Courts, Wide Awake!

19.07.18

There’s another way this we works—that is, another way it’s meaningful to us as music listeners. Whether we listen to an album alone (or on headphones), or with others at a live show, we are among a community of listeners. That listenership is what young bands dream of—not just to have their art and passion celebrated, but to accompany the commons, to provide points of connection between people. We want to be with others, and even in our solitude we have each other in mind. This is music’s pathos,[1] the polis[2] of listenership. We are together in our lives with music, no matter how popular or obscure our soundtracks.

____________________________________

But we can be I too, and to do so is to fix ourselves momentarily, or visit ourselves in a particular moment. And this helps us distinguish other I-s and we-s, like the I that is with other I-s in the audience at a show: we were there. Whereas the we that was I and is now another I is another we from which to observe the show. Those we-s together manifest the complex experience of listening to music, and being alive.

So allow me if you will to move between we and I as it suits me, and describes my experience. So that choosing I or we is an inflection, and a vantage (or coordination, a constellation of selves). I thought about Book Album Book as a way of listening to music and teaching music writing before I thought to make it a more specific, sited writing practice. And more recently, reading Hanif Abdurraqib’s music and culture essays in They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us helped me recognize the ways our listening is sited, how we reach through time and space as we listen, as we think, as we write. In my imaginary conversation with Abdurraqib, whom I have not met, we talk about what this means for listening together, how that togetherness envelops listening with other people and with other selves: us then and now. We have these conversations with our favorite writers and musicians: reading, listening, and writing are this ongoing conversation between artist, listener, artifact, and context (including time, place, and space).

____________________________________

No apologies / and fuck Tom Brady, the opening track on Parquet Courts’ Wide Awake!, “Total Football,” screams. Like they mean it. They may hedge in interviews and say they have nothing against Brady, who merely represents an odious, smug, heroic, dated way of being in the world, but here in Philly, if you scream Fuck Tom Brady you mean business. We fucking hate Tom Brady not just because of the cis male white CEbrO motherfucker he represents, but because we hate Tom Brady the uptight entitled republican asshole that he is. The Philadelphia Eagles make America great every time they sack his ass or watch him fuck up a trick play. Which is to say this was written three days before Parquet Courts played Union Transfer in Philadelphia and the question is not if or even when they will play the song but will we rip off our clothes and throw ourselves off the nearest promontory—knowing our people will catch us—when they do so. Total football, indeed. Shout-out to the Eagles, who told the false president they had to wash their hair but fuck you for the invite.

____________________________________

We’ve lost so much over the past few years. Of course, people we love, people we know and don’t know die every day. Sometimes we learn their names after they die,[3] and sometimes their names are such a part of our lives that we can’t imagine how they no longer refer to living bodies. Yesterday I was restless, walking around Philadelphia, feeling part of and separate from my community. Prince would have been 60 yesterday. I wanted to hear his music with other people, and didn’t understand why it wasn’t everywhere, all day. I walked to my neighborhood corner bar, planning my selections as I passed through shadows in the night. “I Could Never Take the Place of Your Man,” the last song on side 3 of Sign “O” the Times; “Dirty Mind,” which kicks off the album of the same name; “Pop Life,” second song on side 2 of Around the World in a Day. Three albums I will marvel over for the rest of my life. Songs loaded up on the jukebox, I grabbed a beer and played pool with some of the funny, joyful, sad, beautiful fellow regulars at The Barn in West Philadelphia. I lost a couple times but smiled a lot more than I cursed under my breath. And when “Dirty Mind” came on, people shimmied along the bar.

This morning I open my eyes and look at the news: Anthony Bourdain is dead. The olive bread I bought two days ago is sprouting mold on top of the fridge, as the weather starts to press down on us. I walk to the Mariposa Food Coop and feel the sun burn off my grief for a moment. Inside the store, they’re playing Prince. We pick out some food and listen to music together.

____________________________________

We might say this album is about waking up white, and reckoning with complicity in a racist society: that it’s about trying to make culture that is not complicit, and also not dishonest. It’s also about being awake when you want to be asleep. How is it possible that anyone is still asleep? How does anyone rest in peace? How can we use the language in a way that minimizes unjust harm while provoking us to change our lives? This is what art is for. Not to help us dream but to wake us up. Artists have to wake up too. Lying to ourselves every day becomes incredibly easy (“Extinction”).

Parquet Courts was never a complacent band, but on Wide Awake! they aren’t singing about the ubiquity of dust, or house pets lounging in the sun (or using slanted and disenchanted metaphors, give or take a paint-chipped Mardi Gras bead[4]).

____________________________________

If every show felt the way we imagined it would feel, we could forgo the experience. Or forget it. As it is, most of what happens at a show is lost on us, while most of what we catch is immediately dropped. We listen again to the album, and the performance is wiped away. The banter seems trivial, an idle moment between numbers, while some dickhead yells less talk, more rock or doesn’t bother with anything catchier than play a song! We are disappointed the singer doesn’t pause to say something profound, something to mark this day and give us material for the myth we’ll pass on; or the guitarist’s joke falls flat but not flat enough, and just sounds bored. We forget which song had the generous instrumental breakdown that loosened our hips and threw our arms and legs all over the room. We remember the short video we took because we recorded that part, and texted it to a friend who should have been with us.

There’s a power to live music, but we do not necessarily share it. I am looking to my fellows and we are face forward as if we are alone together.

This is a song I sung to myself last night, then transcribed into my phone. Parquet Courts played well, didn’t give us “Violence” but were unselfish with their art. And if something else was missing, something we couldn’t find in the crowd, something we cannot name but know we needed, well, we’ll try to catch that feeling another night.

____________________________________

They opened with “Total Football,” just as they do on the album. It fits, but feels pat, and too soon. Maybe the indie rock crowd is unmoved by sports metonymy, but Tom Brady’s curt dismissal doesn’t launch a parade. Or perhaps anyone who might scream along to that line preferred to be watching the Golden State Warriors finish calmly dismantling the broken Cleveland Cavaliers, a scheduling conflict in lieu of passionate play.

New things happened for Parquet Courts by playing with Danger Mouse, who produced the album. They added another collaborator, with another set of references, who influenced them to draw in more of their listening. The album swings a little—has a beat, not just a rhythm. How would this attend them live? The new songs, especially “Mardi Gras Beads,” which proved itself worthy of that fourth spot, sound warmer, deeper and bigger, fuller live. If “Total Football” didn’t totally hit, it was the first song of the set, and they might have undershot it. You can’t break into a sprint. You need to loosen the hips.

____________________________________

In dreams begin responsibilities, someone else sang. If it stops I’m having a bad dream, and If it stops I’m having an unshakeable nightmare, and But if it stops I’m counting on you, A. Savage declares on “In and Out of Patience.” Can we be both wide awake and dreaming? Of course we can.

———-

[1] We mean this in the sense of “The quality of the transient or emotional, as opposed to the permanent or ideal (contrasted with ethos); emotion, passion” (OED)—and how about that semi-colon! where emotion and passion are between referents, pre- and proscribed, though it all works out—but we evoke ethos as well: “The characteristic spirit of a people, community, culture, or era as manifested in its attitudes and aspirations.”

[2] We mean this in the (Greek) sense of the body politic, which has been marginalized in English usage by reference to the fucking police (see OED, where the latter usage is pre-eminent).

[3] Allow me to ponder the role I play / In this pornographic spectacle of Black death / At once a solution and a problem (Parquet Courts, “Violence”). It’s important to say their names, but not in order to make an adjacent point. More people are starting to care about Black death, we hope, and it’s crucial that we understand we are all being called to care about how Black Lives Matter. Here we honor activists, not musicians, though we are also learning, and here I speak as a writer (acknowledging as well that musicians are writers): we are all activists—but for what? Reader, read on.

[4] A little nostalgia for a long-gone dream, the lost love ballad “Mardi Gras Beads” drifts in strangely as the fourth cut, and though it has no explicit politics, they rub off on it from the preceding track, “Before the Water Gets Too High,” which addresses global warming but in apposition sounds like a latent comment on Katrina.

————

Read the first installment of Book Album Book here.