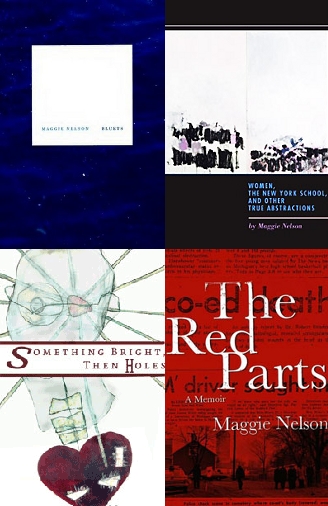

Bluets by Maggie Nelson

08.11.10

Bluets, by Maggie Nelson (Wave Books, 2009) is a love story between a person and an idea. “I had fallen in love with a color … then, it became somehow personal.” Long before Nelson began work on the book, she put on her CV that she was working on a book about the color blue. “I applied for grant after grant, describing how exacting, how original, how necessary my exploration of blue would be. In one application, written and sent late at night to a conservative Ivy League university, I described my project as heathen, hedonistic and horny.”

Bluets, by Maggie Nelson (Wave Books, 2009) is a love story between a person and an idea. “I had fallen in love with a color … then, it became somehow personal.” Long before Nelson began work on the book, she put on her CV that she was working on a book about the color blue. “I applied for grant after grant, describing how exacting, how original, how necessary my exploration of blue would be. In one application, written and sent late at night to a conservative Ivy League university, I described my project as heathen, hedonistic and horny.”

The 240 untitled sections that make up Maggie Nelson’s Bluets fill with various puffs of Goethe, Wittgenstein, film theory, high gossip, plain-spoken confession, contemplations, delirious modes of confusion, postulation, post-adolescent diary-esque feelings (this is not meant as a pejorative), dreams, spells, criticism, and personal anecdote:

“Different dream, same period: Out at a house by the shore, a serious landscape. There was a dance underway, in a mahogany ballroom, where we were dancing the way people dance when they are telling each other how they want to make love. Afterward, it was time for rough magic: to cast the spell I had to place each blue object (two marbles, a miniature feather, a shard of azure glass, a string of lapis) into my mouth, then hold them there while they discharged an unbearable milk. When I looked up you were escaping on a skiff, suddenly wanted. I spit out the objects in a snaky blue paste on my plate and offered to help the police look for you, but they said the currents were too unusual. So I stayed behind, and became known as the lady who waits, the sad sack of town with hair that smells like an animal.”

It must be said upfront that Maggie Nelson could have worked this out as a book of poetry if that’s what she had wanted to do early on. Which is to say, for a book that might actually be an essay, which might be a lyrical essay, for a long work that “blurs genre,” she fills the requirement of what good poetry must do, which is deliver new ways of talking and looking and thinking, and helping us to look and think.

For instance, Manhattan looked at from within itself during daytime is “dank providence,” a man sings Joni Mitchell in “heartbreaking drag,” and on the worst days Nelson finds herself in the situation of “baby-shit yellow showers at my gym, where snow sometimes fluttered in through the cracked gated windows.”

Several plot lines move in and out of the book, appearing beneath the greater clouds of the loss, love and desire. Several high peaks occur through the book as well, which Nelson points back to throughout. We get the first one early on: “I had received a phone call. A friend had been in an accident. Perhaps she would not live…when I walked into my friend’s hospital room, her eyes were a piercing, pale blue and the only part of her body that could move. I was scared. So was she. The blue was beating.” Nelson comes back often to the injured friend, the pain she becomes witness to, and the ability to endure the suffering associated with having become a quadripalegic.

“After a few months in the hospital, my injured friend is visited by a fellow quardriparalytic as part of an outreach program. From her bed she asks him, If I remain paralyzed, how long will it take for my injury to feel like a normal part of my life? At least five years, he told her. As of next month, she will be at three.”

By including these care sessions with her friend, Nelson gives to us her understanding of how people who share a true unselfish love nonetheless still have ontological curtains between them, “pain I can witness and imagine but that I do not know.”

By including these care sessions with her friend, Nelson gives to us her understanding of how people who share a true unselfish love nonetheless still have ontological curtains between them, “pain I can witness and imagine but that I do not know.”

The severity of this makes light of Nelson’s own long-term depression and the puzzling mix of advice given to her by professionals. We also get a comical series of stories about her experience with self-help books: “I pick up a book called The Deepest Blue. Having expected a chromatic treatise, I am embarrassed when I see the subtitle: How Women Face and Overcome Depression. I quickly return it to its shelf. Eight months later, I order the book online.” And later: “Drinking when you are depressed is like throwing kerosene on a fire, I read in another self-help book at the bookstore. What depression ever felt like a fire? I think.” At the advice of a colleague, eventually Nelson gives up on trying to master her depression, even when it hurts. “Last night I wept in a way I haven’t wept for some time. I wept until I aged myself.” And, “I have been trying to place myself in a land of great sunshine, and abandon my will therewith.”

To abandon inner will, for Nelson, is to enter into a tribal wildness, or oblivion. “I could let myself be fucked mercilessly by many strangers at once, as in my first sexual fantasy.” Psychedelic dreams and vulgar fantasies populate Bluets, and as with the other topical elements, Nelson remains dutiful to the truth about her dark obsessions.

Nelson is not afraid to take a chance by making herself vulnerable to the reader each time she circles back to her own failed relationships:

“One of the last times you came to see me, you were wearing a pale blue button-down shirt, short-sleeved. I wore this for you, you said. We fucked for six hours straight this afternoon, which does not seem precisely possible but that is what the clock said. We killed the time. You were on your way to a seaside town, a town of much blue, where you would be spending a week with the other woman you were in love with, the woman you are with now. I’m in love with you both in completely different ways, you said. It seemed unwise to contemplate this statement any further.”

Nelson leverages the science of color, the active work our eyes must do to make a coherent scene out of the messy waves of color information, against the lover’s discourse she employs: “this is the so-called systematic illusion of color. Perhaps it is also that of love.” Nelson closes with a tender blow: “I believed in you.”

You may think, as I did, that a book on blue isn’t a new idea. Nelson says “I feel confident enough of the specificity and strength of my relation to share.” You may also call to mind William Gass’s treatise on blue. Nelson addresses his pronouncement that the blue we want in life is only found in fiction, as “Puritanism, not eros … I will not choose between the blue things of the world and the words that say them: you might as well be heating up the poker and readying your eyes for the altar.”

By rifling through various modes of conveyance, Nelson has taken a kaleidoscopic density of thought and pulled it through her own lived human experience, toward a huge, pleasurable end result. It’s as if the universe has expanded a little in order to accommodate new mass, new light, a new star.

____________________

Buy Maggie Nelson’s Bluets here.

Related Articles from The Fanzine

Jeff T. Johnson on Thalis Field and Leslie Scalapino

Kevin Killian on Tattoo Artist, Historian and Sexual Renegade Samuel Steward