Blood and Breath in High Fidelity: A Review of Hanif Willis-Abdurraquib’s The Crown Ain’t Worth Much

21.09.17

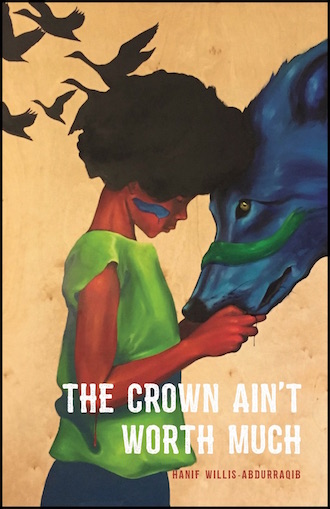

The Crown Ain’t Worth Much

The Crown Ain’t Worth Much

by Hanif Willis-Abdurraquib

Button Press

$16

I say moist / and first think of / the eager and

swallowing mud / the bullet that burrowed into Sean’s chest / on

Livingston Ave / the country of dark red / that grew across his

white tee — “In Defense of Moist”

The Crown Ain’t Worth Much is written in blood: the blood of our ancestors, the blood blanketing a screaming newborn, the blood of black boys slain by the state, the warm-blooded boys on the court guarding kicks and gold. When I read this stunning debut collection, I imagined blood seeping through the pages and forming Rorschach blots on the table. Hanif Willis-Abdurraquib is testing us. He knows we haven’t been paying attention. He knows we’re running out of time.

This sense of urgency is established in the first poem and pushes us through the entire collection. Willis-Abdurraquib exercises control over the breath of his readers like a conductor coaxes notes and rests from an orchestra. He knows the importance of breath on the visceral reading experience and how our fits and pauses influence the meaning we glean from the lines. He knows our stops and uses a dazzling array of narrative and poetic structures to produce substantive effects. For example, “On Hunger” consists of long prose blocks that lack punctuation. Since the reader must attend to many words in between breaths, we experience breathlessness as the narrative weight builds:

a king is only named such after the blood of anyone who is

not them pools at their feet and grows to be a child’s height

before running down a hill

This state of breathlessness is a layer of empathy to process—the speaker and other figures in Willis-Abdurraquib’s poems are exasperated at best and gasping in vain at worst, as illness, gunshot wounds, and the clenched fists of the police overtake breathing.

In “All the White Boys on the Eastside Loved Larry Bird,” the breath of the reader achieves a staccato pace because the narrative build-up is contrasted with conceptual space via the slash:

if i sweat enough i will be fed / or something will be built / but not

bear my name when it is finished / i tear open a hamburger and

my fingertips are slick with grease / i hold them to the sky but no

breeze comes / always the eager mouth / never the hand that feeds

I don’t want to quote the last lines of poems in this review but I will mention that many of the poems end on a remarkable note because of the control Willis-Abdurraqib wields over the last image and breath of each work. “September, Just East of the Johnson Park Courts,” “Dispatches from the Black Barbershop, Tony’s Chair. 1996.,” “Windsor Terrace, 1990,” and “I Mean Maybe None of Us Are Actually From Here” are examples of how a final line can make a poem go on forever.

Willis-Abdurraquib references many pieces of black art and culture, including rappers, R&B singers, songs, films, and fashion trends. Many characters in the poems are ancestors speaking from the grave. These references elevate the terrain from the speaker and their particular situation in Columbus to issues faced by many generations of black diaspora. In “Ode to Kanye West in Two Parts, Ending in a Chain of Mothers Rising from the River,” the speaker hears his ancestors speaking:

you know we ain’t

rupture this country’s spine and unearth all its gold for you people to cocoon

your teeth in it

The Kanye West reference, coupled with the appearance of ancestors in the first half of the poem, as well as the depiction of the speaker’s grief in the second half, conveys the complexity of black pain and the things black people consume in an effort to overcome pain and take control of a situation. Most of the time, the media depicts black people buying gold and wearing kicks as childish consumers rather than thoughtful patrons. In this poem, there are multiple black perspectives explored.

Willis-Abdurraquib uses his poetics of blood and breath to map the barbershops, basketball courts, and other physical spaces of Columbus, Ohio onto complex human interiors that are often rendered in one dimension or completely erased by violence, gentrification, and other agents of white supremacy. These layers of complexity are spoken within single lines and poems and build throughout the entire collection. The Crown Ain’t Worth Much is like a high fidelity album of a young, black heart beating death and living in its wake. Willis-Abdurraquib writes:

here. take this mixtape I made. it is just 30 minutes

of the wind. how it sounds when being cut by something heavy.