Unusual, Dirty Mementos: An Interview with David Nutt

25.03.19

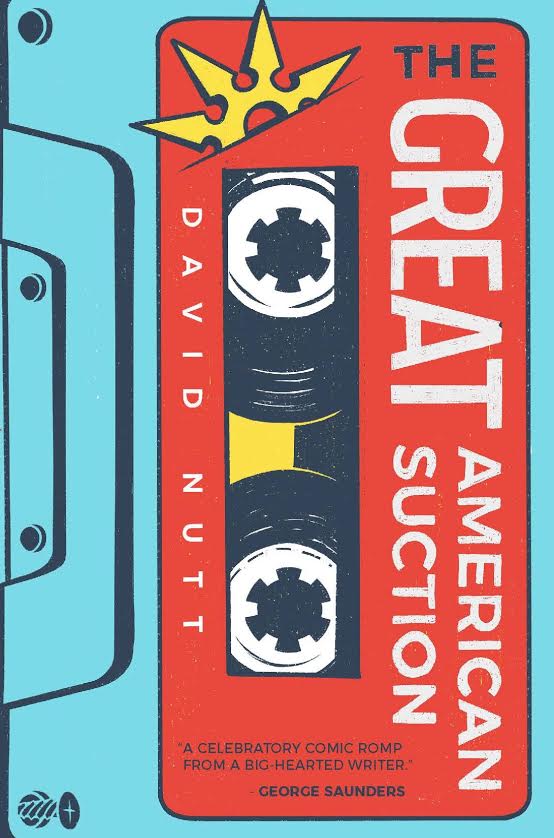

Early on in David Nutt’s wild romp of a novel, The Great American Suction, which has been raved about from the likes of Dana Spiotta to George Saunders to Sam Lipsyte, the protagonist, though that word has almost never been further from the truth, Shaker, no pro at anything, is looking for free food with his cousin, Darb, who like Shaker, partakes in the occasional huff of glue to keep the circuitry fried. The two hunt for sustenance and that’s the general thrust of the book: survival.

Although the tilt-a-whirl goes in directions one could never guess. Shaker is at odds with his neighbor and her teenage daughter, though at times they have détentes to discuss his ex-wife’s hot-and-cold musical career. He’s wronged so many folks in town that a mysterious committee hires the local bar muscle to make his life miserable, or more miserable, by spot-cleaning everything in his apartment. Shaker works at landscaping with a bunch of other misfits—Thin, Munk, Roderick Bartholomew—and they get high on exotic puffer fish between badly buzzing down people’s lawns.

Eventually, Shaker takes in with a woman, who impersonates his ex-wife, and her invalid husband in a ramshackle manor. In the meantime, Shaker finds solace in building a garbage monument with the assistance of his two silent, militia member buddies, The Tully Brothers. Which still only scratches the surface of what goes on in the just over 200 pages of this careening novel. Shifts and pivots aside, the propulsion isn’t even really the plot. Or the characters. For me, it’s more in the unbridled language Nutt hurls in knotty chunks. Every other sentence could be a yearbook quote or Instagram caption or last words blipped out to dying rovers across the universe in the future. It’s a masterpiece of wrecks and ruins.

GK: Can you talk about the impetus for this particular book? I know you’ve got other irons in the fire, other novel and story manuscripts in various states of revision, but what were the beginnings of The Great American Suction?

I started the novel, more or less accidentally, in the summer of 2009. I had left my job as a newspaper copy editor and was gearing up to enter the MFA program at Syracuse University, mostly as a way to wait out the various hemorrhages and failed triages that were bleeding the newspaper industry dry. I figured it would be nice to show up at workshop with a new story under my arm, something with wet fur, a bit of baby fat. The story quickly metastasized into a novel about two burnout pals building monuments out of junk. It was very much in the mode of those early, bombastic Thomas McGuane novels that have wounded antagonisms at their core.

But the draft I wrote was ghastly bad. Too rushed, malnourished. So I started over from scratch and went a lot slower. After a while, some of that McGuane baggage fell away, and the plot, the characters, everything got weirder. When I graduated in 2012, this book was my thesis. I felt pretty good about it. I patted myself on the back for a job well done and sent the manuscript off to agents, indie publishers, total strangers. All I heard back was “no.” A glorious choir of no. Then I spent the next six years, off and on, ripping the book apart and rebuilding it, growing less and less sure of what I was doing.

Where did Shaker come from?

As far as the origins of Shaker, I had a premature sense in my early-to-mid-thirties that I had possibly botched my life in irreparable ways, that I had blown opportunities, squandered goodwill, disappointed loved ones and friends, sabotaged whatever future idea I had once entertained for myself, and it was probably too late to do anything about it. Here I was in this prestigious MFA program, surrounded by brilliant faculty and encouraging peers, and I was lugging around all this sadness and regret and self-pity.

So I got a dog. I started dating a woman who ultimately became my wife. I eventually realized nothing is ever truly botched-beyond-repair. I also realized that, regardless of how well you patch up the botchings, your life can—and will—fall apart all over again. That’s just what life does, and that cycle, that endless loop, can be oddly reassuring and is really the spine of the book.

Gary Lutz has talked about his page hugging vs. page turning, i.e. the reader who wants to slow down by being immersed in the words of the page vs. the reader who tumbles wildly forward to sniff out the next plot point. Your book walked that fine line for me in making me want to do both. From a framing standpoint, how much of this did you plot out first?

This is a copout answer, I know, but for me plot is the thing that just sort of happens. One character trots out on stage, opens his or her mouth, and suddenly the show has started. Another character ambles up, burps something in response, and that generates a nice friction. Now there’s fireworks. Each explosion leaves behind some craters and wreckage for the characters to trip over or agonize about, or maybe not even acknowledge at all because these characters are now half-blind and powder-burned, maybe a bit delusional and a little bitter, maybe some undetonated ordinance is still lying around…

This is a copout answer, I know, but for me plot is the thing that just sort of happens. One character trots out on stage, opens his or her mouth, and suddenly the show has started. Another character ambles up, burps something in response, and that generates a nice friction. Now there’s fireworks. Each explosion leaves behind some craters and wreckage for the characters to trip over or agonize about, or maybe not even acknowledge at all because these characters are now half-blind and powder-burned, maybe a bit delusional and a little bitter, maybe some undetonated ordinance is still lying around…

I always have a hazy notion of where the story is headed, but the real thrill is finding opportunities to veer off course. You enjoy these detours while staying vaguely cognizant there is a place you want to end up at. Then you finally get there and your arms are full of unusual, dirty mementos you collected along the way. Kind of like a monument made of trash. Hopefully stuff connects, holds together. And hopefully there are some tantalizing loose threads that hint, maybe, at a greater mystery you’ve been unconsciously birddogging all along.

The real trick for this book was once I had the whole thing framed and fleshed out—all these elaborate backstories, cause-and-effect conflicts, everything arranged in logical and linear order, and so many spiffy sentences, basically four or five years of semi-regular labor—I went back and ripped out the ligature. Cut the connective tissue. Burned the backstories. This infused a lot of the white space in the book—and this book has a lot of white space, between chapters and sections, free-floating scenes—with a kind of secret life, anticipation. It also ridded the book, I think, of the hack psychologizing that often results from tedious over-explanation and character history. It took me a long time to realize this is where the book’s narrative energy comes from. The sudden leaps, moment to moment, island to island, iceberg to iceberg. Energetic prose can help—the language will always lead you in the right direction—but the real tension and momentum come from quick cuts, narrative hopscotch.

My golden rule: Just keep disappointing your characters, let them do the wrong thing and suffer the consequences, and you have yourself a merry little nightmare of a story.

There are so many twists, turns, unexpected relationships, banter, hidden motives, alliances, etc. that if you had planned it all on post its I feel like you’d be some kind of mastermind. The elements arising organically somehow make me sleep better at night.

Yeah, the fact that I spent so many years on the book—hammering on it, setting it aside for long stretches, then coming back with only a blurry recollection of the last revision—led to a more layered plot, lots of weird resonances, accidental echoes, serendipitous repetitions. The scary thing is now I feel like I need to spend ten years on every novel I write.

Can you remember a major shift or moment where you really surprised yourself?

There’s this whole drug manufacturing subplot that I tossed into the book without much thought. The characters were peddling methamphetamine. But after five years or so, meth felt played out. One day a coworker mentioned that he saw something on TV about dolphins getting high on puffer fish. It’s kinda jarring, because we always think of dolphins as being this evolved species, and it turns out they’re just idiot junkies like us. It took a while, but eventually I jettisoned meth in favor of the more incongruous puffer fish, even though the mechanics of how a human smokes puffer fish remain kinda dubious. The initial impulse of writing the book was to take the sort of traditional, grimy, blue collar, trailer park type narrative—with its minimalist writing and stoic tone—and let it get strange, surreal, playful, without losing the bleakness of regular ‘ol life. The puffer stuff did that for me. Situations in the book that we’ve seen a million times on TV, in movies—drug parties, basement labs, etc—no longer felt so shopworn. They popped more. This encouraged to me find other dead spots in the novel and push them farther, unmoor them.

That old Beat writer axiom of “first thought, best thought”? My first thought is my most pedestrian thought. And my second, my third, my thirteenth, my thirtieth. I really do need to flounder a while.

Was there a moment or scene or character even that didn’t make it into the final cut and why?

This is pretty inside baseball, but the first draft of the book was told in the first person. The narrator’s buddy, and eventual rival, was a loveable, dolty drug-dealer named Sharky, who was so lovable, in fact, he hijacked the book. I had to nix him. A year or two later, though, I realized I missed Sharky so I gave him a standalone story of his own, published in Green Mountains Review as “Superior Parachutes.” Sharky was once again the lovable buddy, and once again he hijacks the story, but now with all sorts of sexual confusion and remorse and smothered yearning in the mix. Probably the best story I’ll ever write, and something of a dry run for the book that The Great American Suction eventually became.

There is that belief out there that dialogue needs to be more varied for a sake of verisimilitude. I think the slick talk really works for your novel, because even though it’s written in the third person, the narratorial voice is so strong and has such a specific language that we’re clearly getting everything filtered through their hazmat suit. What was your process behind working through and revising your dialogue?

Yeah, I have a fetish for stylized dialogue. I know this kind of thing can drive very sensible readers crazy—“All the characters in the book talk the same! Real people don’t sound like this!”—but I just love it. It’s a kind of world-building, that old chestnut, I suppose. For my money, nobody writes better dialogue than Joy Williams and Don DeLillo. Their characters’ speech is always off-kilter and cracked in a same-y type of way, but that’s how they charm me.

I do make some effort to tweak the sound of each voice somehow, specific tics, phrasings, malapropisms. I know writing dialogue can be a chore for some writers—it can feel fraudulent or hokey or like a big info dump—but for me it’s always been great fun. When it’s not great fun, when it starts to feel like drudgery, that’s usually a tell that the characters don’t want or need to speak at all. There is a pair of brothers in the book, a two-man militia, who in early drafts were garrulous assholes, constantly badgering Shaker, belittling him. It got tedious, too shticky. So I cut all their dialogue. Suddenly they were mute, and this made them blank and more menacing. It also somehow made them more sympathetic. This happened with a few other characters, too—they’d reject whatever dialogue I tried to cram in their mouths, so I took the words away—and then it became a pattern, a kind of condition.

The cumulative effect is like a plague of silence creeping across the landscape of the novel. I realized so much of the story really is about language, the vitality of it, the instability, the terminal silence that awaits us all. That whole Beckett trip.

One of the things I enjoyed about your stylistic dialogue is that most of your characters are people pushed to the fringes of society, yet their witty banter breaks cliches of, like you mentioned, that stoic tone that we so often see associated with the working class. I always thought this odd since I know some working class folks who are the greatest yappers. Can you speak to that sense of world building and character building in relation to class?

It seems to me if you’re going to build a terrarium, you should pick the most interesting wildlife to stock it. Human beings are such strange animals, and I have a real fondness for fuckups, rubes, charlatans, philistines, mild cases, the never-taken-seriously. Because I think this is how most of us feel, you know, as we all bumble around the dank, claustrophobic terrarium of everyday life.

And I like irreverence in art. The seemingly insignificant, the unsubstantial. When no one is looking, you can smuggle in some big ideas that don’t call too much attention to themselves and, therefore, can percolate in hopefully exhilarating ways. Like, the gentle rivalry between a pair of insolvent glue huffers in an imaginary Ohio becomes a Trojan Horse for some sticky notions about authenticity and existential repetition and our national woe. Again, it’s one more way of unmooring the novel from the predictable. Part of that unmooring is paying attention to the kinds of characters who don’t always have the camera trained on them, and letting them be their weirdest, wildest selves. To not only capture their private agonies, but also their contradictions, their lapses and failures, and their very oddball joys. Give them a language, the best language, to declaim all this. Don’t lean on rehashed, twice-baked typecasting. Try not to pander. I see that as one of the few compassions we have left, you know?

Dave, one of the things I really admire about this novel is the paragraph work. They strike such a fine balance between imparting information, moving us through action, giving us crunchy bits of language. Can you give us a before-after and maybe some of your thought process behind the edits?

Old version:

The Yarn Barn is not such a nuisance to a man of Shaker’s pale temperament. There is scant barn in its ovoid appearance, and parking is free, but this does not prevent his cousin, Darb, from picketing the plaza on his more lucid days, complaining of malevolent labor practices in tropical territories that have yet to be specified. Darb’s homemade sign is an embarrassment of balsa wood and masking tape that reads: Unravel the Yarn Barn Conspiracy. There he stands on his court-designated, three-foot-wide allotment of pitted sidewalk, the signboard leaned on his hip, sipping something cranberry-colored from a crumple of styrofoam.

Revised version:

The Yarn Barn is not such a nuisance to Shaker. His only protest is there isn’t much barn in its appearance. And yet, Darb stands in front of the strip mall on his court-designated, three-foot-wide allotment of pitted sidewalk, the signboard leaned on his hip. Shaker has to tip his head sideways and squint to read this one. Unravel the Yarn Barn Conspiracy is inscribed in purple sharpie and shoe polish. Darb’s knotty fingers and the groin of his jumpsuit are likewise blotched. Shaker itches his own chin stubble. He tries to nod intelligently. His cousin nods back at him while sipping something cranberry-colored from a crumple of Styrofoam. The sidewalk area around him is inundated, all variety of litter.

So just to pull back the curtain here: I really tried to slow the frantic pace, shorten the sentences, and spread out the avalanche of detail. There’s a lot of unnecessary gunk in that old version. “Malevolent labor practices in tropical territories that have yet to be specified” is a cute riff, but it’s overly wordy and it does the same job as “Unravel the Yarn Barn Conspiracy.” I was fond of the shabby sign construction stuff, but it seemed better to spotlight the mess Darb has made of himself with his materials. It sharpens his character. The streamlined sentences and slower pace opened up more room for a reaction from Shaker. We see him read the sign, we get to process his bewilderment, and we also see him do this little back-and-forth nod dance with Darb. We also don’t realize Darb is Shaker’s cousin until the end of the paragraph. I think this adds some mystery to the moment. Who is this guy? Why are we here? The reader hopefully leans forward a little more.

A lot of this shit is Fiction Writing 101 and really demonstrates what a slow learner I am.

Gian DiTrapano from Tyrant gave me some wonderful Yoda-like advice when he read the early version of the manuscript. He said, “You’re swinging for a knockout, sometimes several knockouts, in every sentence. Think like a boxer. Step up, swing, step back, take a breath. Step up, swing, step back, take a breath. Pace yourself.” It’s tempting to want every sentence to be this glorious dazzling item that readers will instantly fall in love with and tattoo across their torsos. But sometimes you gotta pry open a little space so the best bits can resonate, so the reader has time to register them, marinate a while. I started sniffing out opportunities to be more subtle in my own fussy way. A line like “Shaker itches his own chin stubble” isn’t super interesting or tattoo-worthy, but it has a nice acoustical balance. “Shaker/stubble” gives the sentence symmetry. There’s a pleasing assonance between “itches/chin.” That “own” is an odd disruption (would Shaker really be itching his cousin’s chin stubble?) but I like the stiltedness, and it connects thematically because we soon learn that Shaker is rattled by a recent nightmare in which he was wearing another man’s face.

So I raked through the book a bunch of times and tried to do more of that.

One of the things that struck me about the book was this kairotic sense of now while also, in some ways, feeling timeless. Like it’s such a distinct book about contemporary America and our preoccupations with capitalism and trash, yet it also has that David Ohle sense of being almost without time. Or lost inside of it. Part of it is rarely mentioning major landmarks, but also ignoring brands and even markers like acknowledging people’s ages. Was this a linguistic choice based on the sentential resonance (or lack thereof) of those brand names?

Yes, yes, yes. All of the above. I love novels that are simultaneously in and out of time. Here and not. On a pragmatic level, it makes sense not to peg your work to a particular date, so it doesn’t feel like a relic or artifact with a limited shelf life. And when I choose to incorporate actual relics and artifacts, I like to use them as a way to draw together disparate eras, play up the parallels, history as one continuous looping present.

A sturdy example of this: the various music formats in the book. In an early chapter, a character uses what looks like an iPod. Then cassettes start to crop up. At the end of the book, vinyl is back on the scene. I wanted there to be a sense of technology devolving. And a lot of rural places are like that in a way, the music, the fashion, there’s often a lag that puts people a few years behind. At the same time, though, all the hip kids are buying vinyl nowadays and cassettes are the new DIY punk trend de jour. Tapes, for god’s sake! Totally baffling. Nothing ever dies in our mass-produced, mass-consumed, mass-regurgitated world.

As a general rule, I steer away from brand names—it’s just more fun to be cryptic and make shit up—but sometimes there’s a wonderful sounding word you can’t help but drop in, to vary the pattern. And it’s not just products, it’s places. The America of the book’s title is certainly an off-brand America.

Can you remember some of the things you went back to over the course of making The Great American Suction that consciously or subconsciously shaped it?

I’m not much of a list maker, but I do subscribe to that idea that writers intentionally curate their influences. And sometimes the biggest influences are the things you’re reacting against. In my twenties, I was smitten with all the classic American postmodernists—Pynchon, Barthelme, Gaddis, Coover, etc.—but by the time I started this novel I had grown fatigued by that stuff. Too much brain strain, I guess.

So, instead, I really nourished myself on the crop of American writers in 1970s who bridged the experimental sixties and minimalist eighties, writers like McGuane, DeLillo, Stanley Elkin, Barry Hannah, Joy Williams, Renata Adler, and Rudolph Wurlitzer, folks who captured the cultural burnout of that exhausted decade in rich, clangy language. But by the time I was finishing my book, a lot of those old postmodernist influences had started to creep back in. The most significant literary lodestar, however, was James Robison’s novel The Illustrator, and that book’s fast angular turns, rawboned humor, the boom-whiz-bang prose. The kairotic sense of now you mentioned? That is Robison for me. Every sentence is leaning drastically forward, like a daredevil alpine skier, slaloming forth into the what next.

Other stuff, like music and movies? The National’s melancholy turtleneck absurdism. The Boston band Pile and their post-punk baroque. The junkyard stomps and serenades of Tom Waits’ Bone Machine. Pretty much anything from the Coen brothers, that mix of the brainy and the gleefully lowbrow, the crowd-pleasing and the elliptical. The glacial chiaroscuro humanism of Bela Tarr films. All the verbose homicidal fuckups in the theater of Martin McDonagh. The photographs of William Eggleston and Gregory Crewdson, vivid and otherworldly, but in very different ways. That’s the dream, I think, to somehow attain that range.

Last question: Hob Brock?

The name, of course, is a cute allusion to the fiction writer Hob Broun, who I discovered in grad school when I took a lecture class taught by Gary Lutz. Broun’s Inner Tube thrilled me. Such a smart, nervy book. The character Hob is Shaker’s boss, and he oversees a yard crew comprised of sketchy drug casualties. Hob seems to have the kind of weary moral conscience that Shaker lacks. He recognizes how clueless our protagonist is, but still tries to give him a few opportunities, a few second chances. Then he sits back, folds his arms, and watches Shaker bungle every one of them. In this regard, Hob is a lot like the book’s author — by which I mean, he’s one more skittish animal in a long chain of skittish animals and you probably shouldn’t trust a single word he says.