A Song About Overthrowing Capitalism: On Ryan Eckes’ General Motors

19.03.18

Did the dream of speed begin with the birth of the car? Or was that the dream of escape–of hopping in the car and going, leaving your life and responsibilities behind? And is this desire for speed and escape a particularly American thing? Bruce Springsteen has said that the Animals’ “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” is every song he has ever written, about which poet Ryan Eckes notes, “It’s not a song about overthrowing capitalism but of escaping it.”

Did the dream of speed begin with the birth of the car? Or was that the dream of escape–of hopping in the car and going, leaving your life and responsibilities behind? And is this desire for speed and escape a particularly American thing? Bruce Springsteen has said that the Animals’ “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” is every song he has ever written, about which poet Ryan Eckes notes, “It’s not a song about overthrowing capitalism but of escaping it.”

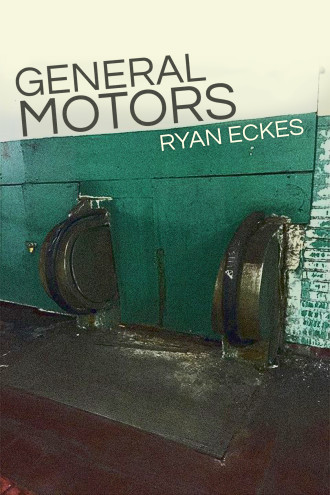

In General Motors (Split Lip Press), his third collection of poetry, Eckes offers another vision for America–a glimpse at how different things could be if people were to recognize their collective power and reclaim public spaces. General Motors is a timely, alive, and necessary collection.

Comprised of three distinct sections, the book opens with a series of prose poems called “chase scenes.” Nearly all of the twenty-one poems in this section begin with the word “we’re,” as in “we are somewhere” or “we are doing something”–playing chess, unsnapping horse’s shitbags, doing unpaid work, and sometimes literally driving. The opening sentence establishes the scene, and from there the sentences and ideas fly, frequently propelling forth in unexpected directions. There is a raw energy, similar to what one finds in The Stooges’ “The Passenger,” which Eckes’ “we” find themselves dancing to in an early scene, the chorus repeating “and I ride / and I ride / and I ride.” The poems serve as vehicles, transporting the reader from one point to another–an experience Eckes details himself late in the collection when he notes that a Ted Greenwald poem brought him “here,” to this moment in thought and life: “It got me here, the poem, dropped me off, thanks for the ride.”

In addition to immediately establishing the theme of speed, “chase scenes” also open the theme of possibility. It’s ultimately this possibility that is driving the poems–whether it’s a potential date, “call on me, call on me. let’s see what happens,” or something larger, “the king is dead, and the queen is dead, and the night is fat with pawns.”

This idea of possibility is pervasive throughout the collection, and it’s what gives Eckes and his friends the reason to keep going. The poems inhabit a landscape of late capitalism, complete with “liberty motel, liberty gas. liberty thru and thru,” but if we can get one more dance, win one more basic right in the courtroom, or have one more night driving around town, then it might all be worth it. In “aida,” a long, single-stanza poem named after the author’s grandmother, Eckes asks (sans question marks), “what is regular life / why do you believe in it.” The poem, which appears in “strikes,” the third section of the book, makes an argument that there are ways to be alive despite the daily grind of work, that desire and, more importantly, the pursuit of desire is where one can really feel alive–i.e. it’s all in the chase.

Despite the title calling to mind Detroit and other former auto factory cities, General Motors is all about Philadelphia, where the author was born and where he continues to live. Philadelphia locales are name-dropped, from Old City to McGlinchey’s to the Boulevard. The heart of the collection, “spurs,” is made up of a series of poem-essays that discuss the development of Philadelphia’s transit system, including how racism and corporations, like General Motors, shaped it, and how Eckes’ own family history is wrapped up in it. One of the most moving poem-essays in the book, “Passyunk spur,” discusses South Philadelphia, its history and gentrification, while also exploring the speaker’s own failed relationships. Eckes writes, “Before the wildlife was ‘preserved,’ of course, all of South Philly was wild. Weccacoe, it was called by the Lenape. That’s supposed to mean ‘peaceful place.’” After discussing the predatory nature of the Philadelphia Parking Authority (PPA) and OCF Realty, who is responsible for much of South Philadelphia’s gentrification, he writes, “Every word is a spur, an outgrowth, a departure. Language, like the city, is wild, even while it inhibits our freedom, our ability to make peace. I think Weccacoe now means this: to make poor, or to systematically fuck the poor.”

There is a lot of fight in this book, which again speaks to the pursuit of desire: the desire for a better, more just world. And in this fight, there are clear enemies, including capitalism, the rich, and the police who enforce the will of the rich in order to protect capitalism. In an early “chase scene,” the speaker is protesting outside of a shareholders’ meeting for Sallie Mae. He says of the police, “they won’t let us in the shareholders’ meeting because we’re not rich and we don’t believe in fucking people over.” In “Northeast spur,” Eckes claims, “The American solution to a public problem, created by private industry, is usually to find a way to steal from the public.” In addition to clear enemies, there are clear victims too, from the public, to Eckes’ own friends who have to find ways to fight off the despair brought on by capitalism, and to people like Darius McCollum, who has Aspberger’s syndrome and has been arrested repeatedly for “impersonating transit employees for no money for over 30 years.” Eckes writes how it is the illness of our society that makes McCollum’s life impossible:

“He got picked on in school, and when he was 11 a classmate stabbed him in the back with scissors. He found refuge in the subway, befriending MTA employees who taught him how to operate the trains and used him happily as a source of free labor. McCollum, a black man, feels more at home in the subway than anywhere and knows more about the MTA than anyone. But the MTA refuses to offer him any type of job. They even refuse to let him volunteer at the MTA transit museum.”

McCollum was most recently facing 15 years in prison for stealing a Greyhound bus, despite driving its passengers on time to their destinations. Eckes draws inspiration from McCollum, who, he says, “insists on his own belonging, unauthorized […] he refuses the system’s refusal of himself.”

Eckes ruminates on a Philadelphia that would have been, if only the city had more public transportation available, specifically considering the public and how they might come together. This belief in the public also ties into Eckes’ own work as a union organizer, details of which are peppered throughout the collection. This is hopeful work–work that is driven forward by the desire to improve each other’s lives, to improve community. In “Roxborough spur,” Eckes writes about skipping school and riding the train: “But that feeling on the el, which was a satisfaction of the need for movement, was a feeling of becoming something else, and that need to become something else is the need for public space, the need for a public, period.” He continues, “And I want to say that this need, which is also the need for collective power, unauthorized, is the only thing that can save us.”

Eckes ruminates on a Philadelphia that would have been, if only the city had more public transportation available, specifically considering the public and how they might come together. This belief in the public also ties into Eckes’ own work as a union organizer, details of which are peppered throughout the collection. This is hopeful work–work that is driven forward by the desire to improve each other’s lives, to improve community. In “Roxborough spur,” Eckes writes about skipping school and riding the train: “But that feeling on the el, which was a satisfaction of the need for movement, was a feeling of becoming something else, and that need to become something else is the need for public space, the need for a public, period.” He continues, “And I want to say that this need, which is also the need for collective power, unauthorized, is the only thing that can save us.”

While there is a lot of struggle captured in this collection, there is also humor, vibrancy, and hope. There are cockroaches the size of alligators sliding under radiators, pigeons shitting on bosses, birds who are pervs, and a serious discussion of the movie Roger Rabbit. Eckes also demonstrates great skill as a craftsman, whether he is working in prose poems that make strong use of sound and rhyme or in lineated verse where he masterfully wields line breaks while avoiding capitalization and punctuation. The book details how messed up the world we live in is, but it also helps provide a road map for a way out, an idea of a different way to live, and a reminder that even when the cd skips, “it’s still good w/ the skips.”