This is Work: A Review of Joe Hall’s Someone’s Utopia

08.10.18

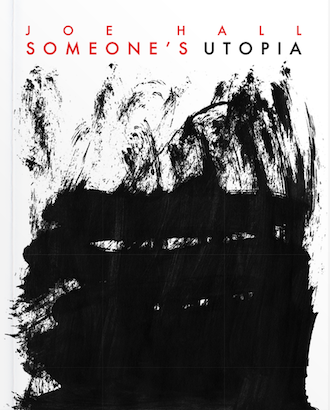

Someone’s Utopia

Someone’s Utopia

by Joe Hall

Black Ocean Press

176 pp. / $14.95

I.

In Someone’s Utopia, out now from Black Ocean Press, the poet Joe Hall examines the language of work and love. Hall is a New York based poet and teacher at SUNY Buffalo. For Hall, this is the next phase of an expansive and enduring project that he began with The Devotional Poems, published by Black Ocean in 2013.

His poetry refracts the language around major general ideas in lived culture. The Devotional Poems looked specifically at the intersection of love, media ubiquity, and technological warfare.

“All of our language has been taxed by war. Allen Ginsberg, “Wichita Vortex Sutra””

Hall examines the language we inhabit today with all its strange collisions and artifacts. The Devotional Poems emerge out of broken and faltering messages. It’s an assemblage of internet language, and the brutality of Abu Ghraib.

He writes, “Can you rise through perforate body armor, sald, and shale?/ Can you rise through a substrate of fractured monitors, bone shards/ Charred engine blocks, chipped motherboards, pottery pieces/ Through LOLOMG, Dear dave it’s been a hard couple weeks”

Many of The Devotional Poems employ the affective register of prayer or psalm. Hall whips up frenzy. He uses sacred address, “fire, the spinning thaumotrope… I want to be… a terminal enveloped in your electricity, your boiler, a router…I can’t stop thinking about this shrapnel.” There is pastiche, and the sense of a descriptive pastiche expanding outwards. It’s a terrific collection and the first installment in a widening project.

II.

Someone’s Utopia turns more explicitly to the paradox of work. Work, like war, gives us meaning as it brutalizes. He presents this ambivalence in mundane descriptive language.

The book is divided into several long sections. The first, Greetings: Play for 2 Voices, imagines various conversations between unnamed interlocutors. These include many references to mediums and the influence of automatic writing. In Séance, Hall incorporates texts that reference spiritualism, “Often a communicating spirit cannot/ hear the sound of the voice issuing from the trumpet and asks—antimnemnop precedeop—“can you hear me, can you hear me?” Emily Anderson describes the collection Someone’s Utopia as, “about the mystery of making…the book’s spectral labor is a séance.” It’s a book about voices.

The next section, $ ∞/HR looks specifically at the practice of work. Hall develops several series including interviews with workers, “Talk Pieces.”

He includes long block quotes that engage with worker’s testimonies:

“Germantown they had a big room up near one of the– they had this huge, huge shredder. And what it’d do was pound the paper, just pounded it into paper dust, then they bundled the paper dust up. They just pounded big, metal teeth and just beat the hell out of the paper and forced it through big, steel metal strainers until it went through the holes, and it went through the holes, it was like paper dust.”

They talk about service industry jobs, and jobs in manufacturing. On a smokestack: “Did it run away?/ Like smoke stacks?/Like the boilers were 100 ft tall/ both our asses/ I can ask, can’t I?/ When it was cooled down.”

There is uncertainty in the working experience: “He paid me so/ being unemployed/ was a better thing/ I guess.”

In these descriptions there is the voice of expertise alongside listlessness and wavering. This is work.

Work and love are intrinsically linked, and nowhere more closely than in the utopian communes of the 19th century. The Oneida Colony of New York, famously celebrated free love for thirty years. In her 2016 memoir of the Oneida colony, Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to Well Set Table Ellen Wayland-Smith captures this strange history. An official company history of Oneida described it’s founding as based in the “best American tradition. Intent on forming a community resembling the early church as described in the Acts of the Apostles and calling themselves Bible Communists, Noyes and his followers pooled all their possessions and lived together as an extended family, striving to become one body in Christ through total selflessness.”

John Henry Noyes, the founder of the Oneida colony, provides the base text for many of the poems in Halls collection. The poet erases and overwrites.

Hall hones in on the Jeremiad nature of Utopian thinking. The founder Noyes demonstrated the classic Messianic characteristics necessary for the establishment of utopian colonies. He experienced hallucinations and manic depression, and so the colony had a kernel of the charismatic visionary. But Hall also parodies the manner the language of the Oneida community resembled a bureaucratic state. There was clear frustration in the establishing of idyll:

“The hour is coming. It has come/ the fertile land follows a diagram/ scatters each one to his home set apart by the State/ orchard, meadow, woodland, the Community near the center/ Indian Reservation, everything/ given me is from you/ Rouse’s Point, Niagra Falls, New York City/ The Community is not a hotel/ the world hates you/ the circle stuck with this dot as a center/ touches the words you gave me/ three principle extremities of the State/ at the mouth of the valley, the beginning of the plain/ The Community, stopping place of all trains.”

The Oneida Colony was explicitly millenarian, believing that endtimes had arrived. It was founded in a Christian communitarian tradition that explicitly favored free love and polyamory. But people living in Oneida could have drastically different experiences, with many of these shaped by their position within shared marriages. In Utopia Ltd, Anahid Nersessian describes the typical “someone” from Someone’s Utopia, as that within 19th century American utopian communities, free love rarely escaped fairly patriarchal schema.

The sense of desire, around owning the shared, inevitably became another source of shame, locked up in the possessiveness of romantic love. This was a core paradox. According to Wayland-Smith, “Relinquishing selfish ownership of property meant nothing, John Humphrey Noyes insisted, unless Christians also relinquished selfish ownership, including sexual ownership, of persons in the form of marriage. Renouncing marriage meant renouncing the orthodox family and the western lineage. And this introduced the paradox of inheritance: the compulsion to survive and pass along information.

Hall captures this compulsion and sadness in vibrant writing:

“We cut three names into a tree/ And when I burned my wrist in the cannery/ So badly it began to bubble,/ You were there with a bucket of cold water,/ Among tons of softening apples/ You smelled like cinnamon burning. That night/ I watched you play piano with Jamie and Evan/ Who were both, at some point, your lovers–/ My heart is in such a confusion,/ Their bows drawing diagrams in the air.”

The Oneida practice of criticism and radical detachment from society only bolstered the punitive elements of romantic love. Community members were publicly shamed and coupled in elaborate rituals. Oneida presents such an enduring example of utopian languor and eroticism, partially because, of course, Oneida itself persists. The heady romanticism of free love and mercantile industry in the late 19th century, transitioned into the familiar corporate industry of the 20th, and Oneida became a company. You can still buy the silverware produced in their factories. The story of Oneida has a lot of the same themes of Generation X rejecting the solipsism of the Baby Boomers for a different kind of solipsism, but an important piece to remember is that the ethic of industry was always there.

And Hall describes the inevitable erotics of work. Hall captures a fascinating portrait of the tensions and small celebrations of working and loving in America. Oneida lives on, alongside these tensions. And Hall has produced a generous collection that can contribute to this ongoing conversation.