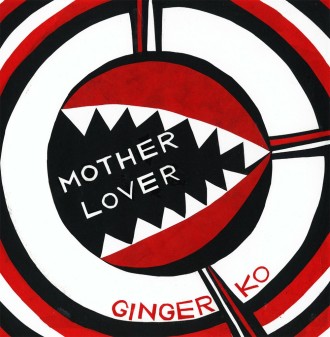

A Review of Ginger Ko’s Motherlover

02.06.15

Motherlover

Motherlover

by Ginger Ko

Coconut Books

78 p. / $14.00

Ginger Ko’s Motherlover is at once supplication and rebuff. I’ve been going back again and again to the book for its moments of airtight agony, unsparing in their demands. Ko’s book opens without disguise: “She wanted more / How could she get more,” and this voice, one that morphs between girl/woman/feral-unbelonging-child, will continue to want and want and want, carrying you through a book whose main concern is to rouse you to attention, to notice what hides in plain view, to make you kick yourself in the foot for being foolish.

Motherlover is a book that tackles big issues. But perhaps “big issues” is an overused phrase. Perhaps “misogyny” or “racism” or “abuse” or even “suffering” are indeed words too “big” to nail down what hides in plain view. In which case Ko remedies with plainspeak:

There is no room in my heart for important men who

surround themselves with flowers. Take the garland of wives

and daughters from around your neck. That you feel safe they

would not choke you makes me sick.

So that there is no mistaking, no mis-attribution of levity, Ko’s poems create a tunnel into which her readers do not realize they have strayed until it’s too late—there is no light at the end, and there is no going back either. But far from being stuck, you realize that being untethered to silver linings or lighted tunnel ends can be all right, actually. You’ll live. As will poetics and its assortments of inquiries and conditions. The book makes you wonder: when a poem lets go of its fascination with redemption, or epiphany-making, what new space does it open up?

After all, the aestheticizing of feminized suffering has a long lineage. Aestheticize suffering: to represent or idealize suffering—if it all sounds rather crude as a description, it’s because it invokes macabre and deficient ideas of suffering as teleological. It doesn’t and should have to be so. Here, what steers interpretation is the shape and form of the representation. The poet Kim Hyesoon, whose writing consistently denies the simplicity of language-as-beauty, once spoke of her visceral representations of female grotesqueness as more than just an aesthetic matter: “Women who have been disappeared by violence are howling. The voices of disappeared women are echoing. I sing with these voices.”

Of the function of poetry as witness Cathy Park Hong wrote, “What if the poet never overcomes? What if the poet hears the same bitter verdict when testimony after testimony has been given? What if that poet—and this is the ultimate emotional transgression that repels the reader who takes comfort in literature as forgiveness—still feels a shadow of hate and it is that hate that disfigures song into something broken?”

What are the powers at work that force a poet to bend her pen so that it writes genteel virtue into experiences of suffering? Ko relentlessly waits out this pressure:

Instead: a metronome on the slowest setting

for a song that lasts the rest of your life.

Ko writes to inhabit temporal and spatial latitudes even as she forbids her reader from partaking in the rare victories she painstakingly describes. This withholding is part of the force of her language:

I can’t stop watching myself from a distance

As my splitjaw gapes

Like a triumphant snake’s

But in the midst of its forcefulness and weight, Motherlover still entertains ambiguities, pauses, equivocations. The book is not wholly directive. But with good reason—and you would be mistaken to read these sparser moments as moments of triumph, lest you reveal your complicity in (mis-)using poetry as personal exoneration. Because even as, in some moments in Motherlover, a poem stews and waits, goes back on itself, asks you for your opinion—expect it to ultimately, flagrantly, disregard every earlier hesitation and snap back into place:

There must be something terribly wrong: I find I can’t live without

most of your body, but would snip out nerves that roll your eyes upwards.

The poems here also bear tinges of the pastoral, but only to appear as dregs vanishing down a drain. Good riddance–a brief glimpse of something we’re not sorry to see gone, sucked away. Sense of being cleansed. Nature is invoked only in order to have its pleasantries short-circuited. Because nature here does not liberate. Rather, it is a site of captivity. (More apt: post-pastoral or anti-pastoral? I am losing track.) Ko writes,

hear instead the wind

feel leaves pat you on the head

hail has hatched the eggs early

a bit of ocean in a cup

a bit of sky in my lungs

color doesn’t reach me here

Or:

I don’t feel all right,

plunging under.

Above all I’m rooted

to the edge of the sea.

In an interview Ko mentions that the first section of the book, “Gaslight,” has its roots in experiences of childhood abuse. But beyond the realm of psychology, of internal despair, of a shrinking self, is a voice that manages to bitterly accuse while it looks at its own shuffling feet, playing at earnest performance of an un-knowing, pre-knowing, innocence:

When I was young you’d take me to the movies.

You’d be furious afterwards if there were sex scenes.

I’ve been sorry to you my whole life

that you couldn’t prevent bad things from happening to me.

The effect of this hyper-performed self-effacement is a sense of exposure. Exposure not as in vulnerability, not as in epiphany, but as in exposé. The ruse is up. And the veil is lifted to reveal some hideous consequences that have to be contended with:

You pat your skin still so dewy plump and say

Maybe I shouldn’t even be here

You say this to me

Who has fought for years to get here

And the world lifts you by the armpits

Gently dips you in

Then lifts you out again

Despite everything: Motherlover doesn’t want your sympathy. Motherlover doesn’t want your disdain. Motherlover doesn’t want your loyalty, even. It only wants you to let it alone, sit back down, and think about the errors of your ways.